确定华南湿润亚热带地区坡耕地径流和土壤流失的不同降雨类型下的最佳山脊做法

![]()

![]()

Agricultural Water Management xxx (xxxx) xxx

Agricultural Water Management xxx (xxxx) xxx

![]()

Identifying optimal ridge practices under different rainfall types on runoff and soil loss from sloping farmland in a humid subtropical region of Southern China

Haijin Zheng a, b,*, 1, Xiaofei Nie a, b, 1, Zhao Liu a, b, Minghao Mo a, b, Yuejun Song a, b

a Jiangxi Provincial Key Laboratory of Soil Erosion and Prevention, Nanchang, Jiangxi 330029, China

b Jiangxi Academy of Water Science and Engineering, Nanchang, Jiangxi 330029, China

![]()

A R T I C L E I N F O

![]() Handling Editor Dr R. Thompson

Handling Editor Dr R. Thompson

![]() Keywords:

Keywords:

Water erosion

K-means clustering

Soil and water conservation Red soil region

A B S T R A C T

![]()

The relationship between different rainfall types, different soil management practices, and soil erosion is not yet fully understood. In-situ observations of soil and water loss on sloping farmland in the red soil region of southern China with a subtropical monsoon environment were taken at 12 runoff plots with four treatments, i.e, down- slope ridges, downslope ridges with hedgerow intercropping, contour ridges, and bare flat land as control, over a seven-year period from 2012 to 2018. During this time, 253 natural rainfall events were classified into three rainfall types by K-means clustering according to the rainfall depth, maximum-30 min rainfall intensity and rainfall duration, and surface runoff and soil erosion processes in relation to the rainfall types under different ridge practices were analyzed. The results show that water-induced soil erosion on the flat land control was

significant, with average annual soil loss of 76.73 t⋅ha—1⋅yr—1, reaching the “intense erosion” classification, and

ridge practices were confirmed to reduce annual runoff and soil loss in all rainfall events by 18.9–62.0% and 68.9–86.3%, respectively. On the whole, rainfall events can be divided into three types: intense, normal, and long-duration. Among them, intense and normal rainfall cause the majority of soil (88.5–93.7%) and water (75.0–83.8%) loss in this area, but the efficiencies in runoff and soil reduction during long-duration rainfall events were the lowest, or even negative on farmlands with only downslope ridges. 20% of the total rainfall events, in which 84.3–92.2% were intense and normal rainfall events, contributed to 29–33% of the total rainfall depth, 68–89% of the total runoff depth, and 94–98% of the total soil loss. Rainfall depth played a dominant role in generating runoff, while runoff accumulation was a main factor influencing on soil loss. Findings from our

study indicate that by choosing a more appropriate ridge practice according to different rainfall types, there can be a positive effect on soil and water conservation.

![]()

Maintaining healthy soil is the foundation of agriculture and is an essential resource to ensure human needs (Amundson et al., 2015), such as food, feed, fiber, clean water and clean air. Soil is a vital part of functioning earth systems that support the delivery of primary ecosystem services (Borrelli et al., 2017; Keesstra et al., 2016a), but is threatened by accelerated soil erosion (Borrelli et al., 2017). Water-induced soil erosion is a main cause of land degradation and declines in productivity around the world (Prosdocimi et al., 2017; Wei et al., 2007). In the last 10 years, the total amount of global soil erosion increased by 2.5% due to changes in land use/cover, with soil loss

ranging from 1 to 2 orders of magnitude higher than the soil formation rate (Borrelli et al., 2017; Amundson et al., 2015). Soil erosion seriously limits agricultural productivity (Mekonnen et al., 2015; Teshome et al., 2016), causes declining soil fertility (Teressa, 2017; Moges et al., 2012) and significantly reduces crop yields (Erkossa et al., 2015; Haileslassie et al., 2005). Soil and water conservation practices (SWCPs) play a vital role in reducing soil erosion and enhancing sustainable land manage- ment, thereby helping to achieve the United Nations sustainable development goals and to deal with the land degradation neutrality challenges (Guadie et al., 2020). The red soil region in southern China is an important agricultural production area (Huang and Zhao, 2014), accounting for 36% of the total cultivated land and for more than 50% of

![]()

* Corresponding author at: Jiangxi Academy of Water Science and Engineering, Nanchang, Jiangxi 330029, China.

E-mail address: zhj@jxsl.gov.cn (H. Zheng).

1 These authors contributed equally to this work.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2021.107043

Received 19 January 2021; Received in revised form 16 May 2021; Accepted 18 May 2021

0378-3774/© 2021 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

the total oil-bearing crops, grain, and agricultural outputs from China (Huang, 2017). Due to high precipitation, hilly landforms, and unsus- tainable farming practices, the red soil region has been facing severe soil and water loss (Barton et al., 2004; Fang et al., 2017). According to Liang et al. (2010) and Zheng et al. (2021), sloping farmland is the

primary source of soil erosion, and the rate of soil loss can reach 98.78 t ha—1 yr—1 in the red soil region. Currently, research examining soil

erosion and suitable control measures for sloping farmland have been successfully undertaken in the region (Shi et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2013; Fang et al., 2017; Dai et al., 2018). However, due to obvious differences in topography, soil types, crop types and farming habits in different study areas, findings from previous investigations report different re- sults, and long-term field observation experiments are still insufficient. Soil erosion processes on sloping farmland are affected by different ridge practices that change the surface micro-topography. At present, research findings about the effect of surface morphology on erosion process are basically consistent. The surface morphology intercepts rainwater through the hollows, changing the source and sink processes and the paths by which water is gathered and dispersed, in turn affecting the surface runoff and soil loss (Appels et al., 2016). Furthermore, compared with flat terrain, concave terrain makes the surface runoff and sediment generation process have a more obvious boundary effect. The greater the undulation and roughness of the surfaces, the more signifi- cant the time delays of surface runoff and sediment generation (Zhao et al., 2018). Many studies have shown that by applying ridge practices on sloping farmland (e.g. ridge hayrick field, tied ridges, and downslope ridges plus contour hedgerows), soil erosion is significantly reduced (Ngetich et al., 2014; Xie et al., 2015; Grum et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2013; Dai et al., 2018). For example, Grum et al. (2017) carried out field experiments during the rainy seasons in arid and semi-arid environ- ments and showed that tied ridges significantly reduced runoff by 56% and improved soil-moisture content compared with normal agricultural practices without ridge treatments. Ngetich et al. (2014) reported that tied ridging was the most efficient measure among selected tillage practices in reducing runoff and sediment yield in semi-arid regions. Compared with flat tillage, ridge tillage is widely used in the red soil region of southern China with humid subtropical environments, where the alternation of dry and wet soil is frequent, and can improve the temperature, light, water, and fertilizer conditions during crop growth. However, poorly-chosen ridging practices are an important cause of high surface runoff and soil erosion. Even with maximum vegetation coverage of 80%, poor choices in ridging can still cause serious soil erosion (Liang et al., 2010). A comparison between different ridge management strategies on sloping farmland need to be examined in order to determine best practices for reducing erosion and runoff

damage.

Rainfall is another primary factor influencing runoff generation and soil erosion (Truman et al., 2007; Girmay et al., 2009; Huo et al., 2020). The impacts of rainfall characteristics (e.g. rainfall intensity, duration, depth and type) on runoff and soil erosion have been and continue to be extensively studied (de Lima et al., 2003; Kinnell, 2005; dos Santos et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2018). Among important rainfall characteristics, rainfall type is the complex primary factor influencing hydrological and erosion processes (Ran et al., 2012). Results from past studies show that due to differences in climate, rainfall in different regions is classified differently and has unique relationships with soil erosion. The signifi- cant relationship between rainfall-runoff-erosion processes is also significantly impacted by management practices (Mchugh et al., 2007; Dagnew et al., 2015). At present, the classification of rainfall types for the study of soil erosion laws in China is mostly found in the Northwest Loess Plateau, which has a semi-arid environment (Wei et al., 2007, 2014; Ran et al., 2012; Fang et al., 2008). The rainfall in the Loess Plateau can be divided into three regimes: short duration and high in- tensity rainfall, medium duration and medium intensity rainfall, and long duration and low intensity rainfall. Among them, short duration and high intensity rainfall is the main cause of soil erosion in this area.

The red soil region of southern China experiences a humid environment with annual average rainfall between 1200 and 2000 mm, and has the greatest rainfall erosivity in China, but there are few detailed studies about the effect of rainfall types on soil and water loss (Zhang et al., 2011; Qin et al., 2015). For example, Huang et al. (2010) used the rapid clustering method to divide erosive rainfall into four types, and selected three of those types to compare the runoff and sediment yield changes of different vegetation restoration models. Another example of relevant research is that Liu et al. (2016) classified 393 rainfall events into five regimes by the K-means clustering method, and analyzed surface runoff, subsurface flow, and sediment loss processes in relation to the rainfall regimes under three land cover types. As previously stated, the red soil region in southern China has the highest rate of rainfall induced erosion in the country, and the management practices used on the sloping farmland are diverse. The relationship between different rainfall types, different soil management measures, and soil erosion remains unclear. The goal of this study was to evaluate the effects of various ridge practices and rainfall types on surface runoff and soil loss on sloping red soil farmland with a humid subtropical environment in Southern China. The specific objectives were: (1) to compare the differences in surface runoff and soil loss under different ridge practices; (2) to determine the responses of surface runoff and soil loss under different rainfall types; and (3) to study the role of different ridge practices on soil erosion control under different rainfall types. Findings from this study could ultimately lead to a better management of agricultural systems in the red

soil region of southern China.

2.1. Study area

The study was carried out at the Jiangxi Ecological Park of Soil and Water Conservation in the Yangou watershed (115◦42′38–115◦43′06′′E, 29◦16′37–29◦17′40′′N), De’an County, Jiangxi province, China. The

study area was 15 km away from Poyang Lake, which is the biggest

freshwater lake in China. The area has a subtropical monsoon climate, with a mean annual temperature of 16.9 ℃ and a mean annual frost-free period of 249 d. Mean annual precipitation in this area is 1449 mm, with precipitation between April and September accounting for about 70% of the total annual precipitation. The topography is generally characterized

by low hills with elevations of 30–100 m. The slopes across the area range from 5◦ to 25◦. This watershed belongs to the typical plain land-

form of a lake area, with a concentrated distribution of sloping farmland. Crop rotations of winter rapeseed (Brassica napus) and summer peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) account for the use of the sloping farmland. The soil, dominated by a red soil developed from quaternary red clay, is acidic to slightly acidic. According to the U.S. Soil Taxonomy, the dominant soil is generally classified as Ultisol. The total organic matter, total nitrogen, total phosphorus and total potassium contents of the

tested soil (0–20 cm) are 2.32, 0.24, 0.25, and 12.53 g kg—1, respec-

tively; its clay, silt, and sand contents are 46.85%, 47.39%, and 5.76%, respectively (Zheng et al., 2021). Natural resources and land use types in the Yangou watershed are typical of the red soil region in southern China.

2.2. Experimental design and agricultural practices

Twelve in-situ runoff plots were constructed on a waste grassland with a 10◦ gradient with similar soil conditions. Each plot was 20-m-

![]() long 5-m-wide, and all plots were adjacent and parallel to the slope. In order to retain external runoff, each plot was surrounded by brick walls that were plastered with cement mortar. These walls were inserted 30 cm into the ground and protruded 20 cm above the surface. A rect- angular drainage trough and a set of circular collecting buckets were installed on the lower slope of each plot to collect surface runoff and eroded sediment. A water-level gauge installed in each bucket was used

long 5-m-wide, and all plots were adjacent and parallel to the slope. In order to retain external runoff, each plot was surrounded by brick walls that were plastered with cement mortar. These walls were inserted 30 cm into the ground and protruded 20 cm above the surface. A rect- angular drainage trough and a set of circular collecting buckets were installed on the lower slope of each plot to collect surface runoff and eroded sediment. A water-level gauge installed in each bucket was used

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

to record the runoff volume for each rainfall event. The construction of runoff plots was finished at the beginning of 2011.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() The twelve runoff plots were arranged in a randomized complete block design with the following treatments: downslope ridge tillage (DT), downslope ridge tillage with hedgerows planted in contour (DT HG), contour ridge tillage (CT), and bare flat land as control (CK) (Fig. 1). There were five planted ridges along the slope of each DT and DT HG plot, and 20 planted ridges that contoured the slope of each CT plot. Each planted ridge was 70 cm wide, 20 cm high, and 200 cm long. In each DT HG plot, Day-lily (Hemerocallis citrina) hedgerow was established every 5 m along the slope by transplanting seedlings on October 26, 2011. Day-lily was planted in two rows at a spacing of 20 30 cm in each belt. In order to reduce surface disturbance, the hedge belts were maintained without tillage during the study period. Bare flat land was employed as the control treatment and the weeds in the runoff plots were manually removed every month.

The twelve runoff plots were arranged in a randomized complete block design with the following treatments: downslope ridge tillage (DT), downslope ridge tillage with hedgerows planted in contour (DT HG), contour ridge tillage (CT), and bare flat land as control (CK) (Fig. 1). There were five planted ridges along the slope of each DT and DT HG plot, and 20 planted ridges that contoured the slope of each CT plot. Each planted ridge was 70 cm wide, 20 cm high, and 200 cm long. In each DT HG plot, Day-lily (Hemerocallis citrina) hedgerow was established every 5 m along the slope by transplanting seedlings on October 26, 2011. Day-lily was planted in two rows at a spacing of 20 30 cm in each belt. In order to reduce surface disturbance, the hedge belts were maintained without tillage during the study period. Bare flat land was employed as the control treatment and the weeds in the runoff plots were manually removed every month.

According to local planting practices, peanut (summer) and oil rapeseed (winter) were selected as crops for annual rotation. Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) was planted in each plot in late-April and har-

vested in late-August. Oil rapseed (Brassica napus) was transplanted in late-October and harvested in late-April. The ridge’s surface was tilled in ridged plots and on the whole surface in CK plots. Soil was ploughed using a hoe to a depth of about 20 cm. Peanuts were sown at a density of about 100,000 holes per hectare with two seeds per hole, and oil rape-

and sediment concentration. Notably, if the drainage trough had accu- mulated bed load, the dry weight of bed load was calculated after sampling and drying, which was included in the total sediment loss of the erosive rain event. Precipitation was recorded using an automatic meteorological situated station 20 m from the experimental plots. The start and end time of a rainfall event, the rainfall intensity and the rainfall depth were recorded. A total of 264 observations were recorded during the entire experiment. Among them, 11 rainfall events were excluded from analysis as they occurred across holidays or festivals during which observations were not made consistently and were diffi- cult to distinguish from independent erosive rainfall events.

2.4. Data processing

In order to assess the effects of ridge practices and rainfall types, surface runoff and sediment yield data (runoff depth and soil loss) were collected for 253 erosive rainfall events from 2012 to 2018. In this study, K-means clustering was used to classify rainfall types according to rainfall depth (P), maximum-30 min rainfall intensity (I30), and rainfall

duration (D). The classification met the ANOVA criterion for signifi- cance (P < 0.05).

Runoff depth (R) and soil loss (S) were calculated using the following formulas:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

seed was transplanted at a density of about 67,000 plants per hectare. The cropping system and cultivation practices used were applied ac- cording to local typical agricultural management in the red soil region of southern China.

2.3. In-situ observations

The observations of runoff and sediment under natural rainfall began in April 2011. To moderate the disturbances caused by plot construction, surface runoff and sediment yield data (runoff depth and soil loss) used in this paper began in 2012. A rainfall event was not considered to be independent unless the rainfall interval was over 6 h (Renard et al., 1997). Surface runoff volume of each runoff event was calculated ac- cording to a pre-determined water level-volume ratio using the water-level gauge installed in the runoff bucket. After each rainfall event, a runoff sample mixed with sediment was collected in an

aluminum box, and sediment concentration was determined by drying the sample in an oven to a constant weight at 105 ◦C. The sediment loss

of each rainfall event was calculated by multiplying the runoff volume

Fig. 1. Study site and runoff plots of different treatments. Note: a and b represent collecting buckets and drainage trough, respectively; CK, DT, DT+HG and CT represent bare flat land as control, downslope ridge tillage, downslope

ridge tillage with hedgerow intercropping, and contour ridge tillage, respectively.

R = A × 1000 (1)

![]() where, R was runoff depth (mm), Q was the runoff volume (m3), and A

where, R was runoff depth (mm), Q was the runoff volume (m3), and A

was the runoff plot area (100 m2).

![]()

![]() S = A × 10 (2)

S = A × 10 (2)

where, S was soil loss (t ha—1), and E was erosive sediment (kg).

Runoff and sediment reduction of ridge management were calculated according to the Comprehensive Control of Soil and Water

Conservation-Method of Benefit Calculation (GB / T 15774–2008) of

China, as:

![]()

![]() ηR = R0 — Rm × 100% (3)

ηR = R0 — Rm × 100% (3)

![]() ηs = S0 — Sm × 100% (4)

ηs = S0 — Sm × 100% (4)

where, ηRand ηs are runoff reduction and sediment reduction, respec- tively; Rm and R0 are the runoff depth of ridged management plots and bare control plots (mm), respectively; Sm and S0 are the soil loss from

ridged management plots and bare control plots (t ha—1), respectively.

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test showed that the data were normally or log-normally distributed. The one-way ANOVA test was used to test for differences in surface runoff and sediment yield between different management types and rainfall types. Spearman correlation was used to illustrate the correlations between the runoff depth, the soil loss, and rainfall characteristics. SPSS 17.0 was used to perform statistical anal- ysis, and OriginPro 2019b was used to draw charts.

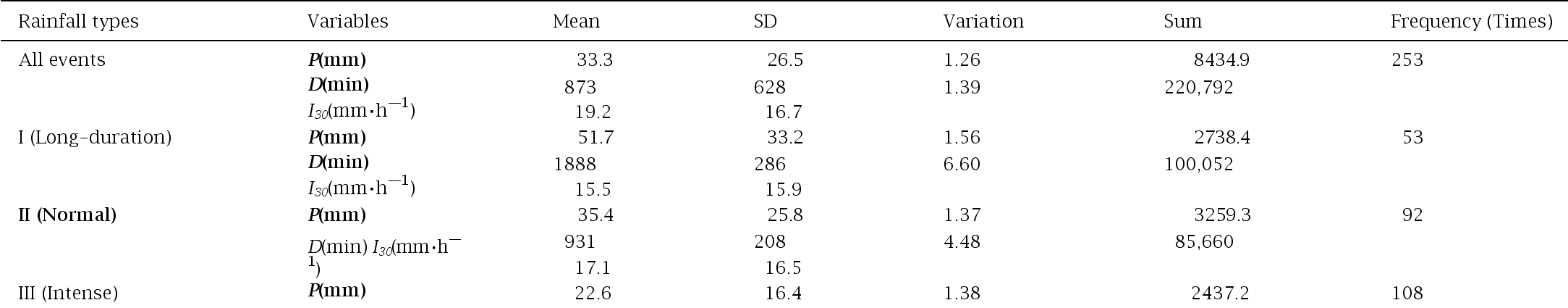

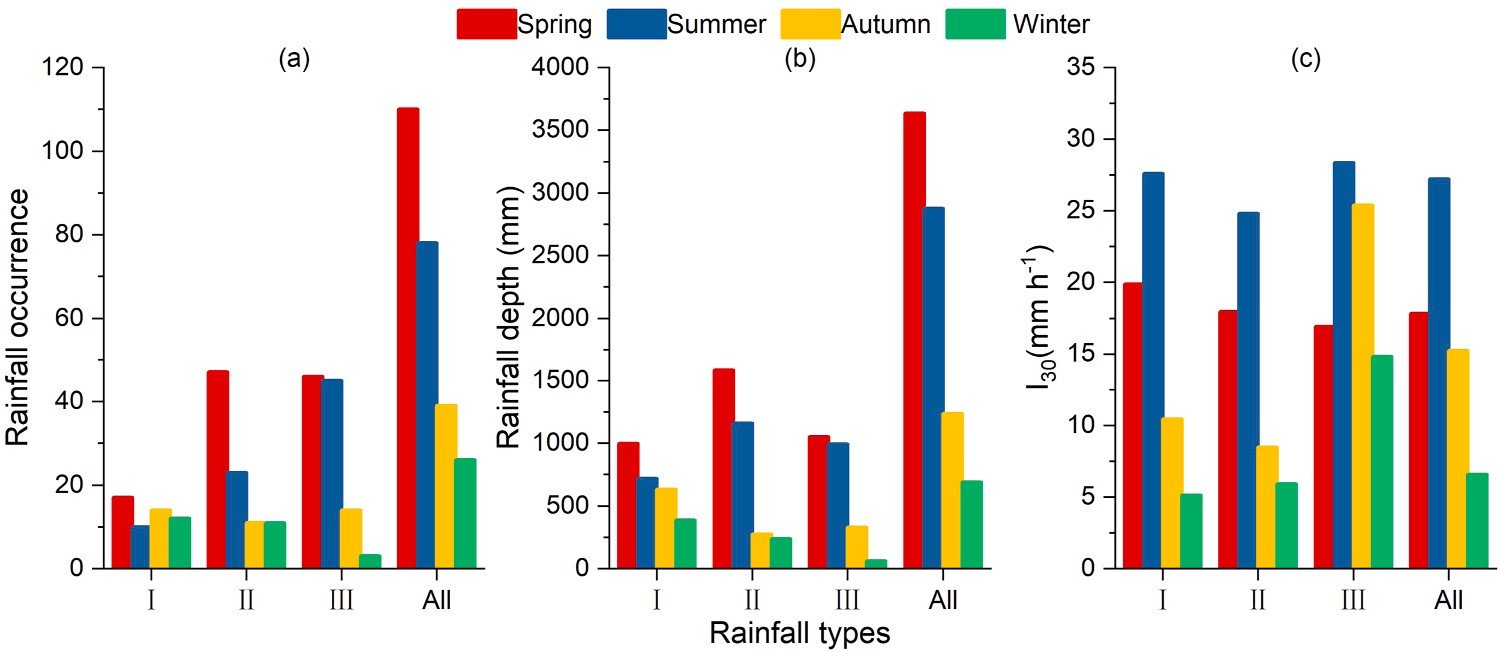

3.1. Description of erosive rainfall events

The 253 erosive rainfall events used in this study were divided into three groups by K-means clustering based on the rainfall depth, the maximum-30 min rainfall intensity, and the rainfall duration (Table 1). Rainfall type III was characterized by intense rainfall with the shortest duration (325 min) and the lowest rainfall depth (22.6 mm), but the

highest maximum-30 min rainfall intensity (22.7 mm h—1). Rainfall

type III occurred 108 times, which was the highest frequency of any

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Statistical characteristics of different rainfall types.

Statistical characteristics of different rainfall types.

1.15

0.98

1.04

D(min) 325 188 1.72 35,080

![]()

I30(mm⋅h—1) 22.7 16.7 1.36

Note: P, rainfall depth; D, rainfall duration; I30, maximum 30-min rainfall intensity; SD, standard deviation.

rainfall type. Rainfall type I, long-duration rainfall, included rainfall events that had the greatest depth (51.7 mm), the longest duration (1888 min), and the lowest maximum-30 min rainfall intensity

rainfall type. Rainfall type I, long-duration rainfall, included rainfall events that had the greatest depth (51.7 mm), the longest duration (1888 min), and the lowest maximum-30 min rainfall intensity

(15.5 mm h—1), but also the lowest frequency, with only 53 such events

observed. Rainfall type II, characterized by normal rainfall, had a moderate depth, moderate duration, and moderate maximum-30 min rainfall intensity; this rainfall type occurred 92 times during the seven years. Considering seasonal distributions (Fig. 2), rainfall type I mainly occurred in spring (from March to May) and autumn (from September to November) with the total occurrence of 31 times and 58.5% probability; rainfall type II mainly occurred in spring with the highest seasonal occurrence of 47 times and 51.1% probability; and rainfall type III occurred both in spring and summer (from June to August), with 46 and 45 times and probabilities of 42.6% and 41.7%, respectively.

3.2. Runoff and soil loss under different ridge practices

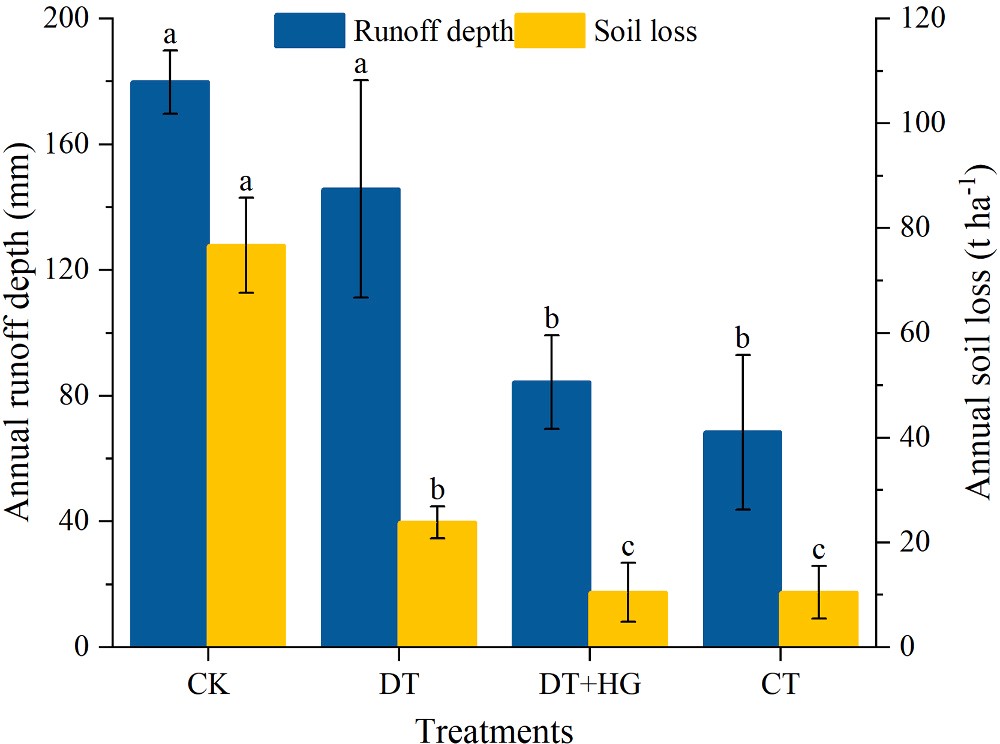

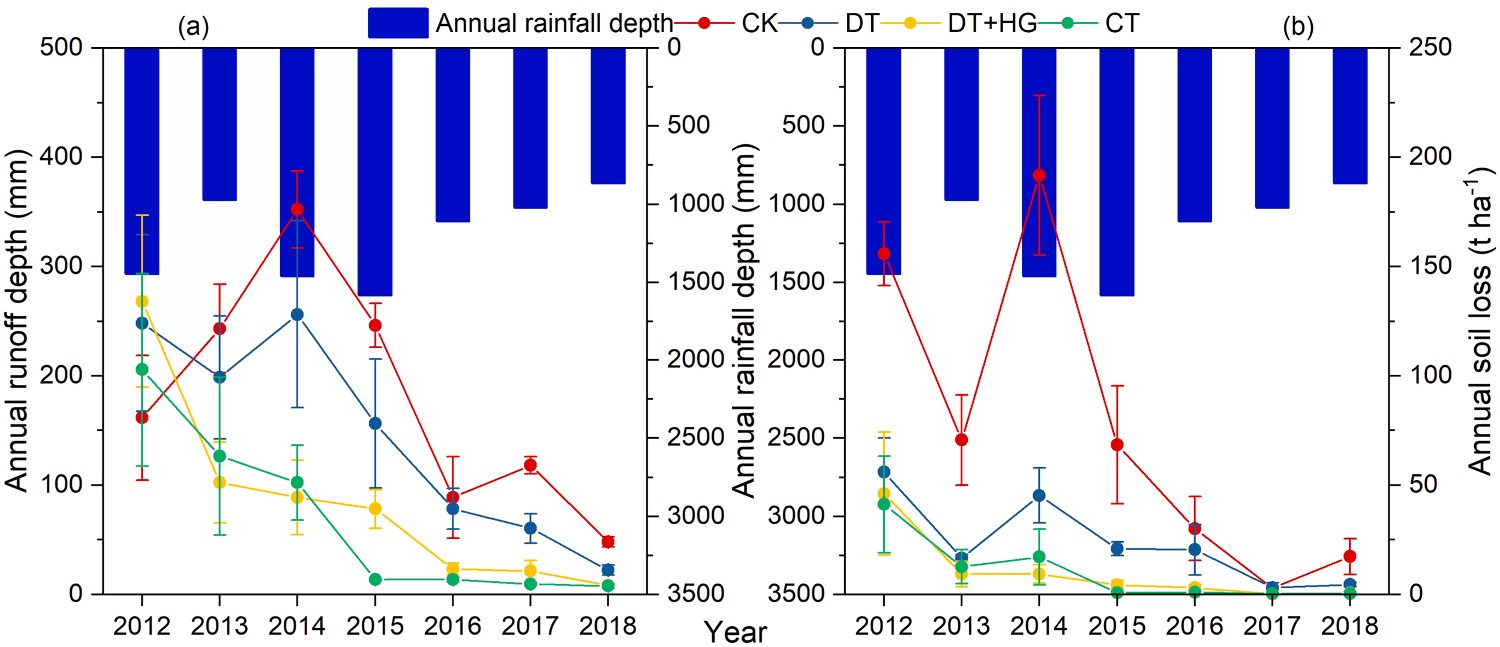

Fig. 3 presents the results of average annual runoff and soil loss from

![]()

the four treatments from 2012 to 2018. It was clear that the runoff and soil loss were strongly affected by ridge practices. Runoff depth was the highest and the lowest in CK and CT, with average annual amounts of

179.86 and 68.40 mm, respectively. The average annual runoff depth in

![]()

![]() DT and DT HG was 145.79 and 84.34 mm, respectively. Runoff depth was significantly (P < 0.05) lower in CT and DT GH compared with CK and DT. The highest average annual soil loss was found in CK

DT and DT HG was 145.79 and 84.34 mm, respectively. Runoff depth was significantly (P < 0.05) lower in CT and DT GH compared with CK and DT. The highest average annual soil loss was found in CK

(76.73 t ha—1 yr—1), which had the poorest surface cover conditions,

![]() followed by DT (23.86 t ha—1 yr—1). The lowest average annual soil loss was found in CT and DT HG (both with 10.49 t ha—1 yr—1). Soil loss was

followed by DT (23.86 t ha—1 yr—1). The lowest average annual soil loss was found in CT and DT HG (both with 10.49 t ha—1 yr—1). Soil loss was

significantly (P < 0.05) lower in all ridge treatments than from the bare flat control. Significant (P < 0.05) differences were also shown in the average annual soil loss between DT and DT+HG, CT.

Fig. 3. Average annual runoff depth and soil loss on the sloping farmland for four treatments in 2012–2018. Note: Different letters indicate significant dif- ferences among four treatments according to one way ANOVA and LSD test (p < 0.05). CK, DT, DT+HG and CT represent bare flat land as control, down- slope ridge tillage, downslope ridge tillage with hedgerow intercropping, and

contour ridge tillage, respectively.

3.3. Runoff and sediment loss from different rainfall types

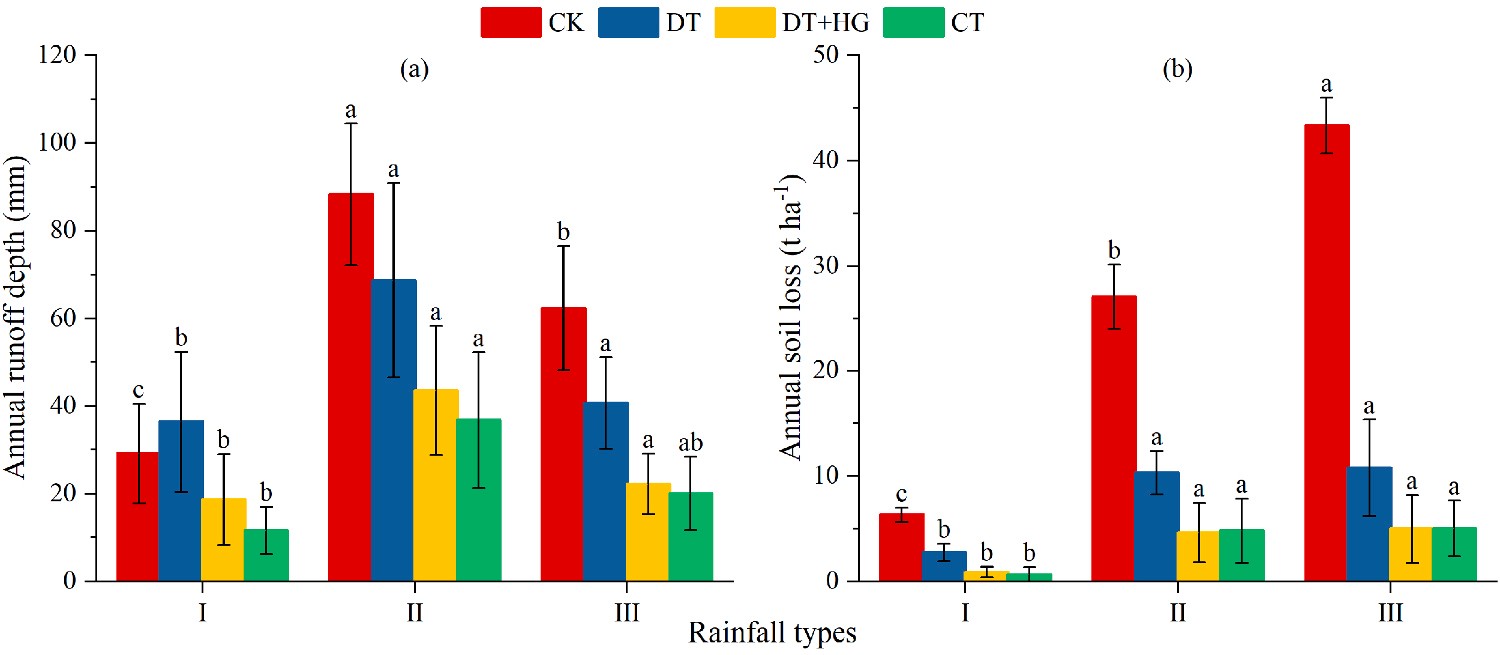

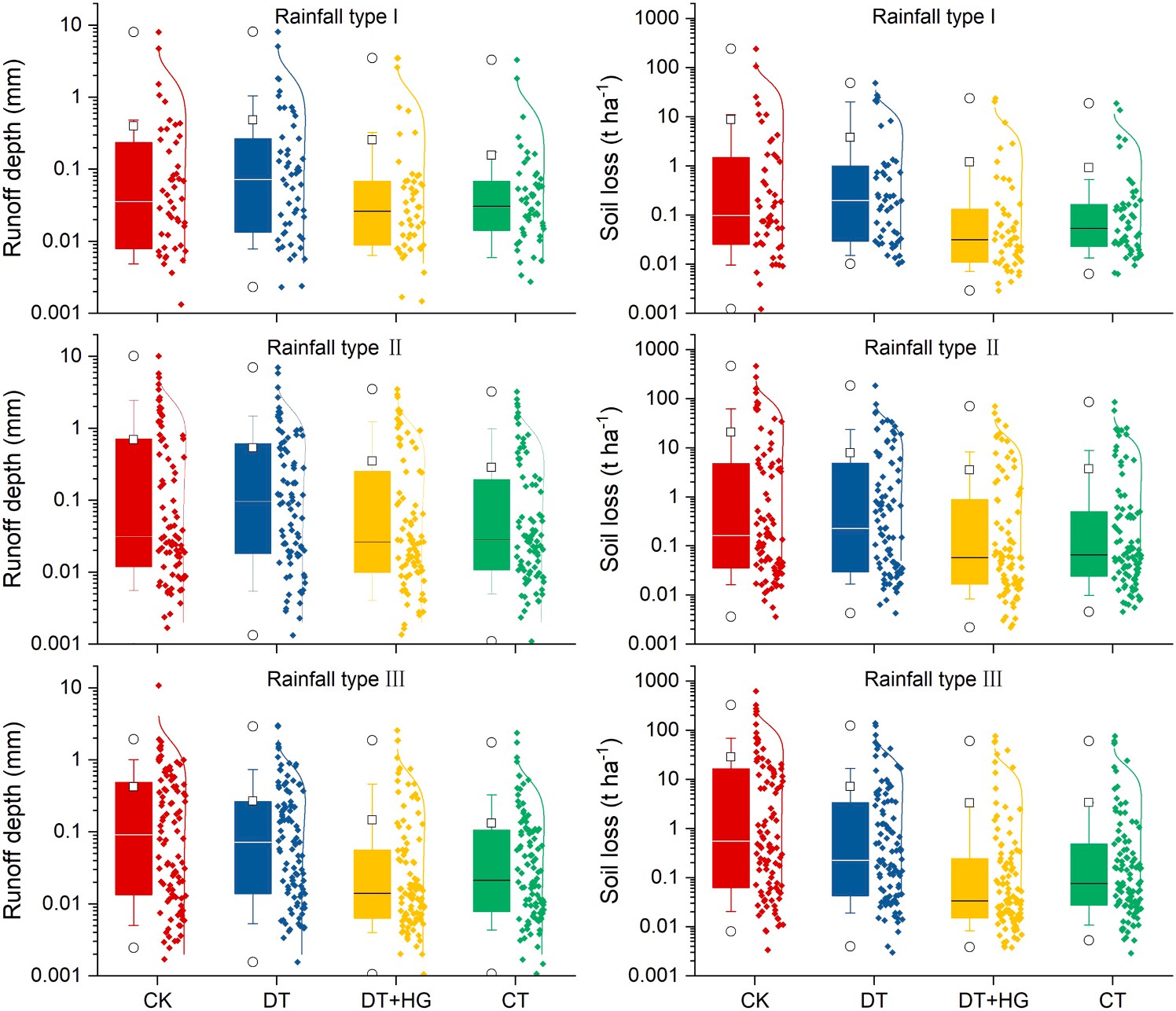

Fig. 4a shows that mean annual runoff depth for the CK treatment demonstrated a significant decreasing trend (P < 0.05) from rainfall type II > III > I. Rainfall types II and III created significantly (P < 0.05)

Fig. 2. Frequency (a), rainfall depth (b) and I30 (c) of different rainfall types under different seasons. Note: Rainfall type I, II, III and All represent rainfall events of long-duration rainfall, normal rainfall, intense rainfall, and all rainfall, respectively.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Fig. 4. Average annual runoff depth (a) and soil loss (b) on the sloping farmland for four treatments under three typical rainfall types in

Fig. 4. Average annual runoff depth (a) and soil loss (b) on the sloping farmland for four treatments under three typical rainfall types in

2012–2018. Note: Different letters indicate sig-

nificant differences among rainfall types for the four treatments according to one way ANOVA

and LSD test (p < 0.05). CK, DT, DT+HG and

CT represent bare flat land as control, down- slope ridge tillage, downslope ridge tillage with hedgerow intercropping, and contour ridge tillage, respectively. Rainfall type I, II and III represent rainfall events of long-duration rain- fall, normal rainfall, and intense rainfall, respectively.

![]()

![]() more runoff depth than that created in rainfall type I for the DT and DT HG treatments. Rainfall type II created significantly (P < 0.05) more runoff depth from CT treatments compared with rainfall type I. As

more runoff depth than that created in rainfall type I for the DT and DT HG treatments. Rainfall type II created significantly (P < 0.05) more runoff depth from CT treatments compared with rainfall type I. As

shown in Fig. 4b, rainfall type III had the highest soil erosion for all treatments, with mean annual soil loss ranging from 5.02 to 43.33 t ha—1 yr—1. Rainfall type I showed the lowest soil erosion for the four treat- ments, with mean annual soil loss ranging from 0.66 to 6.33 t ha—1 yr—1.

Soil loss across the three rainfall types showed significant (P < 0.05)

![]() differences under the CK treatment. Soil loss in rainfall type I showed a significant (P < 0.05) difference from the other rainfall types for DT, CT, and DT HG treatments. On the whole, it can be concluded from Fig. 4 that intense rainfall (type III) events caused more soil loss, whereas normal rainfall (type II) events generated more runoff on the sloping

differences under the CK treatment. Soil loss in rainfall type I showed a significant (P < 0.05) difference from the other rainfall types for DT, CT, and DT HG treatments. On the whole, it can be concluded from Fig. 4 that intense rainfall (type III) events caused more soil loss, whereas normal rainfall (type II) events generated more runoff on the sloping

farmland.

4.1. Effects of ridge practices on water-induced erosion

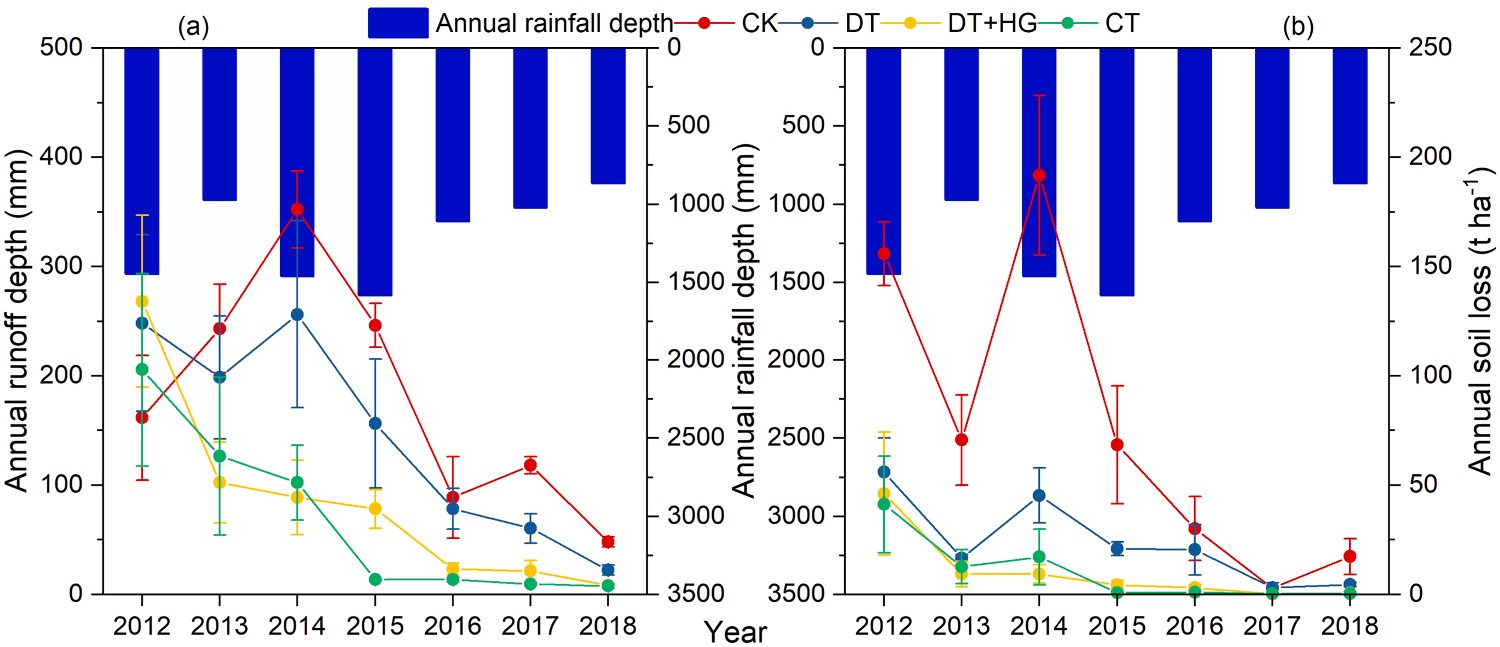

Water-induced soil erosion is a serious issue in the red soil region of southern China (Liang et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2021). Due to the in- crease in cultivated vegetation coverage using a peanut/rape rotation compared to that of bare land, runoff generation and soil loss were reduced by an average of more than 18.9% and 68.9%, respectively, during the seven years of the study (Fig. 3). However, due to poor choice of soil management practices implemented in cultivated areas, there are serious risks of soil and water losses. Experimental results (Fig. 5) showed that annual soil loss from cultivated farmland with a conven-

tional downslope tillage in the first year reached 55.99 t ha—1 yr—1,

reaching classification as “intense erosion” (50–80 t ha—1 yr—1) ac- cording to the Standards for Classification and Gradation of Soil Erosion (SCGSE) issued by the Ministry of Water Resources of the People’s Re- public of China. As the years since the land was reclaimed increased, soil loss from the sloping farmland decreased, but due to disturbances in the

crop rotations, annual soil loss continued to be large (above 15 t ha—1

yr—1). Tu et al. (2018) analyzed the erosion characteristics under an

orchard planting mode in the same study area, and found that soil erosion during the first year after planting was the largest. However, after the trees reached maturity, soil erosion decreased and 64% of the

study years recorded annual soil loss rate with a tolerance of < 5 t ha—1

yr—1. This study showed that soil erosion from farmland was severe and

that crop farmland experienced longer erosion times than the orchard farmland. These were consistent with other research results. Wei et al. (2007) determined that crop land experienced the highest surface runoff and soil erosion in the loess hilly areas of China, far more than those in other land use types. Cropland is strongly affected by human-caused disturbances, which disturbs the soil layer and reduces land coverage (Bagarello and Ferro, 2010). Keesstra et al. (2016b) reported that the highest runoff and erosion amounts were seen in uncovered plots, and the lowest values were identified in covered plots. Shui et al. (2001)

found annual soil loss rate from sloped red soil farmland in the first two years after development reached above 50 t ha—1 yr—1 with higher losses

from crops than orchards. This was due to serious disturbances of the surface soil that caused loose soil early in the planting period, and by the frequent tillage with crop rotation practices that increased soil erod- ibility and the probability of severe erosion during the growing season. On the other hand, frequent tillage and serious disturbances homoge- nized the soils and created nearly uniformly slope at the plot scale, while

![]()

![]()

![]()

Fig. 5. Yearly runoff depth (a) and soil loss (b) on the sloping farmland for four treatments in 2012–2018. Note: CK, DT, DT+HG and CT represent bare flat land as control, downslope ridge tillage, downslope ridge tillage with hedgerow intercropping, and contour ridge tillage, respectively.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

surface runoff and wash was produced nearly everywhere (Cerda` and Rodrigo-Comino, 2020). When efficient prevention and control mea- sures are removed, increased flow and sediment connectivity can cause serious water and soil erosion along the slope (Rodrigo-Comino et al., 2018). The spatially uniformly distributed flow generation and soil erosion in the plot implied that the current tillage was not sustainable due to the lack of sink areas able to reduce the runoff and sediment discharge in the humid area (Cerd`a and Rodrigo-Comino, 2020). Hence, to better prevent and control soil erosion from sloped farming systems with crop rotation, best soil management practices should be under- taken all the time.

![]() Ridge practices are effective in reducing water-induced erosion on sloping farmland with rotating crops. In this study, on average, CT and DT HG treatments significantly decreased annual runoff depth more than 53.1%, and these two treatments decreased annual soil losses by 86.3% when compared with the control. Moreover, after the fourth year of monitoring, the amount of annual soil loss on farmland with CT and

Ridge practices are effective in reducing water-induced erosion on sloping farmland with rotating crops. In this study, on average, CT and DT HG treatments significantly decreased annual runoff depth more than 53.1%, and these two treatments decreased annual soil losses by 86.3% when compared with the control. Moreover, after the fourth year of monitoring, the amount of annual soil loss on farmland with CT and

![]() DT HG treatments was lower (0.30–4.46 t ha—1 yr—1, respectively) than

DT HG treatments was lower (0.30–4.46 t ha—1 yr—1, respectively) than

the tolerable erosion rate (5 t ha—1 yr—1) for this region (Fig. 5). Contour

![]() ridges across the slope can greatly reshape the slope and change the direction of water flow from downward to horizontal, effectively slow- ing the flow velocity and increasing the probability of soil infiltration, forming barriers that trap sediment in runoff water. Generally, contour tillage has the most obvious effect on reducing runoff and soil losses in the early stage of rainfall or rainfall with light intensity (Yang et al., 2013; Dai et al., 2018). In this study, there was an average decrease of 62.0% of the annual runoff depth and 86.3% of the annual soil loss in CT plots compared with the control. The reduction of runoff and soil by hedgerows could be attributed to the hedgerow bases and stems block- ing the path, and to the reconstruction of micro-topography such as a shortening of the slope length and a reduction of the slope gradient (Blanco-Canqui et al., 2004; Sudhishri et al., 2008; Adhikary et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2021). There was an average decrease of annual runoff depth and soil loss of 53.1% and 86.3% in the DT HG treatment compared with the control. It is noteworthy that the perennial hedgerow started to play a role in intercepting sediment in the year after planting, and started to play a role in intercepting runoff during the second year (Fig. 5). These findings are in agreement with former studies. He et al. (2016) and Li et al. (2019) also found that sediment-reduction occurred one-year earlier than runoff-reduction for Leucaena leucocephala hedgerow after planting on purple sloping farmland in Southwest China. Zheng et al. (2021) reported that Hemerocallis citrina hedgerow did not play a role in intercepting surface runoff during the first year after planting, while it did affect sediment in its first year after planting on sloping red-soil farmland in southern China. This is because the first year after planting is considered the adaptation period, in which perennial hedgerows do not intercept runoff from slopes; during the second year after planting, the hedgerow begins to have a mechanical interception effect on runoff and sediment. To enhance the runoff reduction effects of the hedgerow, it should be combined with straw mulching or other methods in the early stages of hedgerow construction.

ridges across the slope can greatly reshape the slope and change the direction of water flow from downward to horizontal, effectively slow- ing the flow velocity and increasing the probability of soil infiltration, forming barriers that trap sediment in runoff water. Generally, contour tillage has the most obvious effect on reducing runoff and soil losses in the early stage of rainfall or rainfall with light intensity (Yang et al., 2013; Dai et al., 2018). In this study, there was an average decrease of 62.0% of the annual runoff depth and 86.3% of the annual soil loss in CT plots compared with the control. The reduction of runoff and soil by hedgerows could be attributed to the hedgerow bases and stems block- ing the path, and to the reconstruction of micro-topography such as a shortening of the slope length and a reduction of the slope gradient (Blanco-Canqui et al., 2004; Sudhishri et al., 2008; Adhikary et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2021). There was an average decrease of annual runoff depth and soil loss of 53.1% and 86.3% in the DT HG treatment compared with the control. It is noteworthy that the perennial hedgerow started to play a role in intercepting sediment in the year after planting, and started to play a role in intercepting runoff during the second year (Fig. 5). These findings are in agreement with former studies. He et al. (2016) and Li et al. (2019) also found that sediment-reduction occurred one-year earlier than runoff-reduction for Leucaena leucocephala hedgerow after planting on purple sloping farmland in Southwest China. Zheng et al. (2021) reported that Hemerocallis citrina hedgerow did not play a role in intercepting surface runoff during the first year after planting, while it did affect sediment in its first year after planting on sloping red-soil farmland in southern China. This is because the first year after planting is considered the adaptation period, in which perennial hedgerows do not intercept runoff from slopes; during the second year after planting, the hedgerow begins to have a mechanical interception effect on runoff and sediment. To enhance the runoff reduction effects of the hedgerow, it should be combined with straw mulching or other methods in the early stages of hedgerow construction.

![]() The least effective measure in reducing runoff and sediment loss was downslope ridge tillage (Figs. 3 and 5). The reason for these phenomena was that the planting ridges were parallel to the slope surface, which was conducive to runoff collection, causing the greatest runoff and sediment yield in the DT plots. The differences of flow and sediment connectivity among CT, DT HG and DT resulted in different effects. Barriers and contour ridges formed on and across the slope disconnected the flow and sediment between rows in the early stage or light rainfall events, and reduced the connectivity even in moderate or heavy rainfall events. The hedgerow created a topographical barrier that contributed to low con- nectivity between the upper and lower hedgerows boundaries for most rainfall events. As more years post-planting passed, hedgerow slope became less connected as more soil collected on their upper boundaries via splash processes and tillage erosion (Rodrigo-Comino et al., 2018). During rare large storm events, a connection occurred between the

The least effective measure in reducing runoff and sediment loss was downslope ridge tillage (Figs. 3 and 5). The reason for these phenomena was that the planting ridges were parallel to the slope surface, which was conducive to runoff collection, causing the greatest runoff and sediment yield in the DT plots. The differences of flow and sediment connectivity among CT, DT HG and DT resulted in different effects. Barriers and contour ridges formed on and across the slope disconnected the flow and sediment between rows in the early stage or light rainfall events, and reduced the connectivity even in moderate or heavy rainfall events. The hedgerow created a topographical barrier that contributed to low con- nectivity between the upper and lower hedgerows boundaries for most rainfall events. As more years post-planting passed, hedgerow slope became less connected as more soil collected on their upper boundaries via splash processes and tillage erosion (Rodrigo-Comino et al., 2018). During rare large storm events, a connection occurred between the

upper and lower hedgerow boundaries. The greatest reduction effects still appeared in the DT HG treatment, even though they had a down- slope ridge. The well connectivity on the slope using DT treatment increased the connectivity of flow and sediment and resulted in the least reduction runoff and soil erosion. In general, the higher the connectivity, the worse the control effect on runoff and soil erosion at the plot scale. To enhance the reduction of soil erosion and runoff, these findings suggest that a combination of measures such as grass hedges and straw mulching jointly provided the greatest reduction of erosion and the least connectivity on sloping farmland with downslope tillage.

![]() 4.2. Response of erosion in red soil regions to different rainfall types

4.2. Response of erosion in red soil regions to different rainfall types

The impacts of rainfall types on runoff and soil erosion have been extensively studied (Wei et al., 2007, 2014; Fang et al., 2008; Huang et al., 2010; Ran et al., 2012; Qin et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2018). Compared with the existing classification results of erosive rainfall in the red soil region of southern China, Zhang et al. (2011) classified five types of rainfall using a 10 mm rainfall equivalent inter- val. This classification method represents the average segmentation of rainfall, and does not reflect the influence of rainfall intensity and other characteristics. Huang et al. (2010) used the rapid clustering method to classify four types of rainfall. However, from the results, one type of rainfall only contained one event, while the average rainfall, duration,

and maximum-30 min rainfall intensity of the other three types of rainfall in decreasing order were type III > type II > type I. This clas- sification result does not reflect the characteristics of different rainfall indicators in a rainfall event. In this study, the rainfall events were divided into three types by the rapid clustering method (Table 1). The

probability of D and P under the rainfall type clustering function sig- nificance test with probability P < 0.0001, and I30 under the rainfall type clustering function significance test with probability P < 0.05

resulted in a better clustering effect. Utilizing this method produced results that were more in line with the actual observed conditions in the red soil region of southern China.

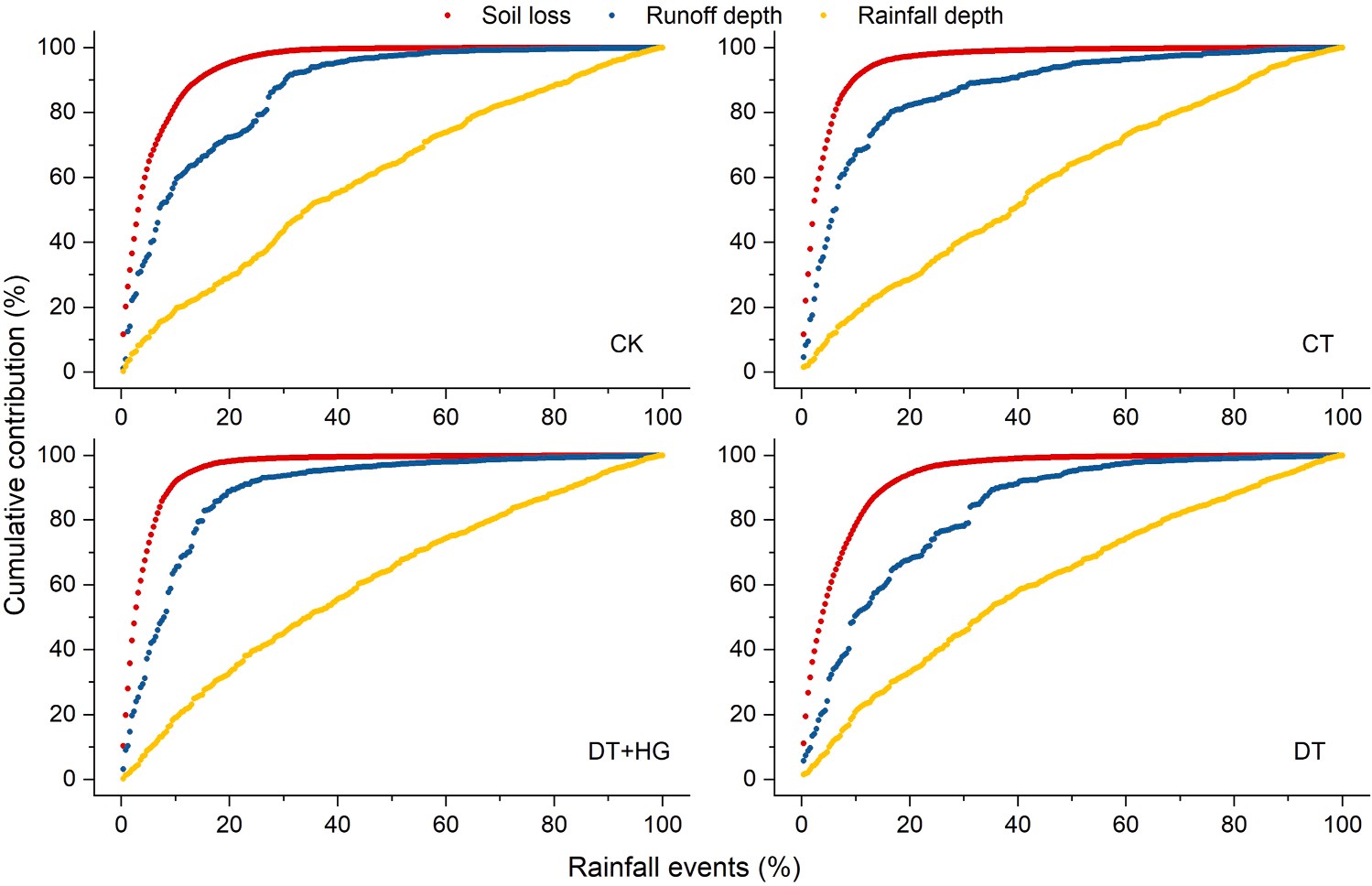

Many studies have shown that different rainfall types can generate various runoff and soil erosion conditions (Jiao et al., 1999; Wei et al., 2009; Qin et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2016; Duan et al., 2020). In this study, the mean amount of annual soil loss for all treatments in order of

greatest to least was rainfall III > rainfall II > rainfall I (Fig. 4), with percentages of 45.2–56.5%, 35.3–45.9% and 6.3–11.5%, respectively. Rainfall III with the highest maximum-30 min rainfall intensity (mean I30 was 22.7 mm h—1), the shortest duration (mean duration was

325 min) and the highest frequency (108 times) (Table 1) created the most soil loss on sloping farmland, and should be the focus of future prevention methods. This result was similar to results from previous studies in the same area (Qin et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2016). Liu et al. (2016) also found that rainfall regime V, with characteristically high intensity, short duration, and high frequency, had the highest sensitivity in sediment yield in the red soil region. Rainfall III events exceeded the soil infiltration capacity and the excess rainfall was lost as surface runoff (Wei et al., 2014). Moreover, the raindrops associated with type III events have high kinetic energy and can damage the soil structure when they hit the ground (van Dijk et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2019). As a consequence, the rainfall III events were assumed to dominate soil loss when compared to other rainfall type events. Other researchers have reported similar results in different areas (Wei et al., 2007; Peng and Wang, 2012; dos Santos et al., 2017). For example, in the Northwest Loess Plateau of China, storms with short duration were also the main rainfall type that caused soil erosion (Wei et al., 2007), accounting for more than 60% of soil erosion (Jiao et al., 1999). The rainfall depth of a short duration rainstorm is between 10 and 30 mm and lasts between 30 and 120 min in the Northwest Loess Plateau (Jiao et al., 1999). Soil erosion in the two regions is mainly caused by storms of short duration and tends to have approximately the same rainfall depth, but the rainfall duration in the Loess Plateau tends to be shorter and of greater intensity

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

than in the red soil region. Many studies have shown that water erosion tends to be caused by a few rainfall events, especially those that are extreme (Duan et al., 2020; Ai et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2011; Huang

et al., 2010). In this seven-year study, 20% of the rainfall events contributed 29–33% of the rainfall depth, 95–98% of the total sediment, and 68–89% of the total runoff on sloping farmland (Fig. 6). Among the 20% rainfall events (51 rainfall events), rainfall type III accounted for

about 60% in the CK treatment, while rainfall III and II events accounted for 37–47% and 43–47% in other treatments, respectively. Obviously, the extreme rainfall in type III and II events played the destructive role in inducing surface runoff and soil erosion.

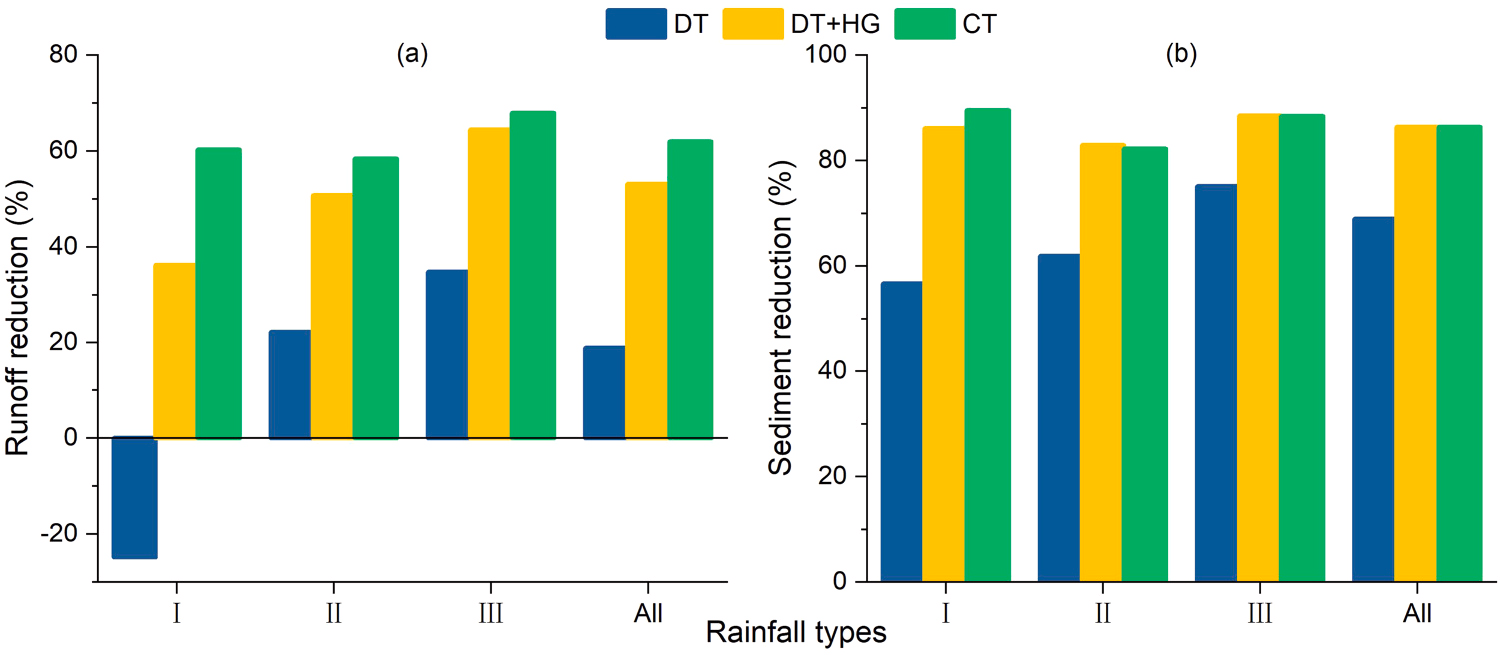

As shown in this study, better performance of management measures could weaken the destructive impact of different rainfall types on water erosion (Liu et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2019). Fig. 7 shows the reductions achieved in runoff and soil loss. As a whole, ridge treatments signifi- cantly reduced soil and water loss for all rainfall events compared with the control. However, the effectiveness in runoff and soil reduction of the ridge measures differed across the three types of rainfall (Figs. 7 and 8). For all ridge measures, rainfall III (intense rainfall) events had the

largest effect on runoff depth (34.7–67.9%) and soil loss (75.1–88.5%), while rainfall I (long-duration rainfall) events had the least reduction effect on runoff generation (—24.8 to 60.3%) and sediment yield (56.6–89.5%). It is worth noting that the rate of runoff and sediment reduction in the DT treatment was the lowest under the three rainfall

![]() types, and even had a negative effect ( 24.8%) on reducing runoff under rainfall type I. In the future, more attention should be paid to managing long-duration but low intensity and high precipitation rainfall events on farmlands with downslope ridges alone. Ridge management reduced soil loss more than runoff under different rainfall types (Fig. 7).

types, and even had a negative effect ( 24.8%) on reducing runoff under rainfall type I. In the future, more attention should be paid to managing long-duration but low intensity and high precipitation rainfall events on farmlands with downslope ridges alone. Ridge management reduced soil loss more than runoff under different rainfall types (Fig. 7).

The effect of rainfall type on runoff and soil loss is associated with rainfall variables such as depth, intensity, and duration. Rainfall depth and intensity were confirmed as the main drivers of runoff and soil loss (Ran et al., 2012; Qin et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2016; Nearing et al., 2017). Past studies have shown that rainfall intensity plays a dominant role in soil loss (van Dijk et al., 2002; Kinnell, 2005), while rainfall depth is the main factor influencing runoff (Mayor et al., 2007; Ziadat and Taimeh, 2013; Huo et al., 2020). Spearman correlation analysis (Table 2) shows the effects of rainfall variables on the runoff depth and the soil loss were different among different rainfall types. For rainfall types I and II, the

rainfall depth contributed more to both runoff depth and soil loss. However, for rainfall type III, the maximum-30 min rainfall intensity contributed more to soil loss than the rainfall depth, and the rainfall depth often contributed more to runoff depth. Results confirmed that except for the CK treatment, the rainfall depth contributed more to runoff generation than the maximum-30 min rainfall intensity for all rainfall events in similar area (Mayor et al., 2007; Ziadat and Taimeh, 2013; Huo et al., 2020). Previous studies have shown that linear, power, or exponential correlations have been used to describe the relationships between rainfall, runoff, and soil loss (Kothyari et al., 2004; Qin et al., 2015; Dai et al., 2018; Huo et al., 2020). In our study, regression analysis

showed that runoff was significant (P < 0.05) and positively correlated with rainfall depth for each treatment, while soil loss was more related

to runoff depth (Table 3).

4.3. Soil erosion control using different ridge practices and other SWCPs

In addition to using different ridge practices, other SWCPs with various anti-erosion mechanisms have been recognized as being effec- tive in reducing water induced erosion. As mentioned above, ridge practice forms both a high convex ridge and a low concave ridge, which changes the micromorphology of the sloping land and affects runoff and sediment connectivity. Each ridge simultaneously contributes to retaining soil and water and increasing precipitation infiltration. Mulching can be used as a useful management practice to control soil erosion rates due to the immediate effect on reducing the high soil detachment rate and runoff initiation, by mitigating raindrops splash erosion and by reducing runoff generation and, especially, sediment losses (Keesstra et al., 2019). Straw mulch is also effective in managing soil and water loss via protection against splash erosion. Dai et al. (2018) found that in southern China, mulch was most effective at controlling water erosion under heavy rainfall, because it provided a buffer for rain drops and increased infiltration. Catch crops and cover crops have also been recognized as effective agronomic practices to promote soil con- servation, mainly by increasing vegetation cover and surface roughness. Rodrigo-Comino et al. (2020) reported the use of Vicia sativa as an effective soil erosion control measure during the first stages of vineyard plantations. Lo´pez-Vicente et al. (2020) pointed that cover crops mini- mized soil loss in permanent cropping systems where the soil was

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Fig. 6. Cumulative contribution of runoff depth and soil loss to all rainfall events on the sloping farmland for four treatments. Note: CK, DT, DT+HG and CT represent bare flat land as control, downslope ridge tillage, downslope ridge tillage with hedgerow intercropping, and contour ridge tillage, respectively.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Fig. 7. Runoff (a) and sediment (b) reduction on the sloping farmland for ridged treatments under different rainfall types. Note: DT, DT+HG and CT represent,

downslope ridge tillage, downslope ridge tillage with hedgerow intercropping, and contour ridge tillage, respectively. Rainfall type I, II, III and All represent rainfall events of long-duration rainfall, normal rainfall, intense rainfall, and all rainfall, respectively.

Fig. 8. Box-and-whisker diagrams with left box and right data which showed a normal distri- bution curve on the right of data for runoff and soil loss under three typical rainfall types. Note: The box boundaries represent the 75% and 25% quartiles, horizontal lines represent the me- dians, squares represent the means, whisker caps represent the 90% and 10% quartiles, the

Fig. 8. Box-and-whisker diagrams with left box and right data which showed a normal distri- bution curve on the right of data for runoff and soil loss under three typical rainfall types. Note: The box boundaries represent the 75% and 25% quartiles, horizontal lines represent the me- dians, squares represent the means, whisker caps represent the 90% and 10% quartiles, the

circles represent the 99% and 1% quartiles, and dots represent original data. CK, DT, DT+HG and CT represent bare flat land as control,

downslope ridge tillage, downslope ridge tillage with hedgerow intercropping, and contour ridge tillage, respectively. Rainfall type I, II and III indicate rainfall events of long-duration rainfall, normal rainfall, and intense rainfall, respectively.

![]()

usually bare due to intense tillage or overuse of herbicides. Terracing is a typical mechanical SWCP that can reduce soil erosion on sloping farm- land. Terraced farmland can shorten the slope length, change the terrain, retain runoff and reduce or prevent erosion. Han et al. (2020) Even suffered from embankment failure, the erosion modulus of terraced land (94.90 t ha-1 yr-1) was still less than that of sloped cropland dominated by rill/gully erosion (112.52 t ha-1 yr-1) in a northern rocky mountainous area of China (Han et al., 2020).

A better understanding of the effect of SWCPs on runoff and soil erosion control could be helpful in determining the timing and selection of management practices to be adopted in different regions. A review conducted for vineyard and olive orchards in Mediterranean areas emphasized how appropriate measures differed between various

climates with different constrains and foci (Novara et al., 2021). Tem- porary cover crop was suggested for drier environments due to water constraints, while permanent species with high ground cover were suggested for wetter environments with a high risk of soil erosion and high yield quality prioritized (Novara et al., 2021). A recent meta-analysis systematically reviewed the efficiency of SWCPs in the red soil hilly region of China (Chen et al., 2020). Hedgerows were among the most effective biological measures for runoff reduction, and contour tillage and ridge tillage reduced runoff by 55% and 39%, respectively; with respect to reduction of soil erosion, the combination of hedgerows and contour tillage performed well with an efficiency greater than 92%, but ridge tillage and contour tillage indicated relatively low reductions in soil loss of 54% and 56%, respectively (Chen et al., 2020).

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Spearman correlation analysis between rainfall parameters, runoff depth and soil loss.

Rainfall types CK CT DT+HG DT

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Soil loss Runoff depth Soil loss Runoff depth Soil loss Runoff depth Soil loss Runoff depth

Soil loss Runoff depth Soil loss Runoff depth Soil loss Runoff depth Soil loss Runoff depth

All events D -0.227** -0.107 -0.115 0.044 -0.041 -0.137* -0.109 0.025

P 0.465** 0.541** 0.409** 0.574** 0.472** 0.658** 0.507** 0.625**

I30 0.721** 0.654** 0.547** 0.490** 0.531** 0.484** 0.640** 0.559** I (Long-duration) D -0.049 0.149 -0.111 0.173 -0.031 0.119 -0.066 0.146

P 0.734** 0.765** 0.488** 0.665** 0.628** 0.674** 0.590** 0.753**

I30 0.692** 0.634** 0.442** 0.503** 0.492** 0.553** 0.505** 0.602** II (Normal) D -0.050 -0.086 -0.105 -0.216 0.001 -0.062 -0.119 -0.108

P 0.761** 0.779** 0.665** 0.723** 0.634** 0.758** 0.730** 0.782**

I30 0.709** 0.707** 0.634** 0.669** 0.574** 0.614** 0.698** 0.671** III (Intense) D -0.243 -0.122 -0.189 0.009 -0.132 0.052 -0.140 0.038

P 0.503** 0.550** 0.394** 0.556** 0.481** 0.644** 0.547** 0.624**

![]()

I30 0.679** 0.607** 0.496** 0.414** 0.547** 0.471** 0.621** 0.485**

Note: P, rainfall depth; D, rainfall duration; I30, maximum 30-min rainfall intensity; * and ** indicate correlations with a 0.05 and 0.01 level of significance, respectively; CK, DT, DT+HG and CT represent bare flat land as control, downslope ridge tillage, downslope ridge tillage with hedgerow intercropping, and contour ridge tillage, respectively.

![]()

Stepwise multiple linear regression model for runoff and soil loss under different treatments (n = 253).

Treatments Multiple regression equation p R2

![]() CK S = 17.406 + 31.448R-0.014D <0.001 0.378

CK S = 17.406 + 31.448R-0.014D <0.001 0.378

intensity). Effects of rainfall variables on runoff depth and soil loss varied among different rainfall types. Rainfall depth plays a dominant role in runoff generation, and runoff depth is the main factor that in- fluences soil loss. The control modes of downslope ridges with hedgerow intercropping and contour ridges were better than downslope ridge modes under different rainfall conditions. We also suggest that more

R = —0.579 + 0.032P <0.001 0.437

CT S = 1.437 + 16.151R-0.002D <0.001 0.538

R = —0.116 + 0.009P <0.001 0.252

DT+HG S = 3.195 + 14.621R-0.109P <0.001 0.509

attention should be paid to managing the impacts of rainfall events of long duration but low intensity and high precipitation on farmlands with only downslope ridges. These results can provide a reference for plan-

ning tillage practices for soil and water conservation on sloping farm-

![]()

![]()

![]()

R = —0.222 + 0.014P <0.001 0.374

DT S = 4.855 + 11.902R-0.003D <0.001 0.326

R = —0.459 + 0.026P <0.001 0.514

Note: S, soil loss; R, runoff depth; P, rainfall depth; D, rainfall duration; CK, DT, DT+HG and CT represent bare flat land as control, downslope ridge tillage,

downslope ridge tillage with hedgerow intercropping, and contour ridge tillage, respectively.

Research-based evidence on the effects of SWCPs on soil erosion control is vital in helping determine whether to adopt the practices or design alternative land management strategies. Although mechanic, vegetative, and agronomic SWCPs played a vital role in reducing soil erosion and enhancing sustainable land management individually, their integration/combination is more effective (Cerd`a et al., 2018; Mekon- nen et al., 2017) and worthy of further study. Moreover, the impact of SWCPs is long-term, not short-term; hence, studies that assess effec- tiveness of SWCPs over time are needed (Keesstra et al., 2019), which would help to achieve the United Nations sustainable development goals and to deal with the land degradation neutrality challenges (Keesstra et al., 2018). It is also a question as to whether economic benefits can be gained from ecological restorations using SWCPs to better determine if a win-win of socioeconomic development and ecological reconstruction can be advocated to achieve sustainable land management (Chen et al., 2020).

This study identified optimal ridge practices under different rainfall types on surface runoff and soil loss from sloping farmland in the red soil region of southern China. Water-induced erosion from newly tilled farmland was severe and lasted a longer time. The selected ridge prac-

tices played a role in intercepting runoff and soil loss, reducing annual runoff depth by 18.9–62.0% and annual soil loss by 68.9–86.3% when compared to bare flat land. We found that the vast majority of runoff (68–89%) and sediment (95–98%) production during the seven-year study was due to a few (20%) rainfall events, mainly belong to rainfall

type III (the highest intensity, shortest duration, and highest frequency) and rainfall type II (moderate depth, moderate duration, and moderate

land in the red soil region with a subtropical monsoon environment.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Founda- tion of China (41761060 and 41601297), the Provincial Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi (20192BAB213022), and the Science Foundation of Jiangxi Provincial Water Conservancy Department in China (201821ZDKT20).

Adhikary, P.P., Hombegowda, H.C., Barman, D., Jakhar, P., Madhu, M., 2017. Soil erosion control and carbon sequestration in shifting cultivated degraded highlands of

eastern India: performance of two contour hedgerow systems. Agrofor. Syst. 91, 757–771. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-016-9958-3.

Ai, L., Shi, Z.H., Yin, W., Huang, X., 2015. Spatial and seasonal patterns in stream water contamination across mountainous watersheds: linkage with landscape

characteristics. J. Hydrol. 523, 398–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

Amundson, R., Berhe, A.A., Hopmans, J.W., Olson, C., Sztein, A.E., Sparks, D.L., 2015. Soil and human security in the 21st century. Science 348 (6235), 1261071. https:// doi.org/10.1126/science.1261071.

Appels, W.M., Bogaart, P.W., van der Zee, S.E.A.T., 2016. Surface runoff in flat terrain: how field topography and runoff generating processes control hydrological

connectivity. J. Hydrol. 534, 493–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

Bagarello, V., Ferro, V., 2010. Analysis of soil loss data from plots of differing length for the Sparacia experimental area, Sicily, Italy. Biosyst. Eng. 105 (3), 411–422. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2009.12.015.

Barton, A.P., Fullen, M.A., Mitchell, D.J., Hocking, T.J., Liu, L.G., Bo, Z.W., Zheng, Y., Xia, Z.Y., 2004. Effects of soil conservation measures on erosion rates and crop productivity on subtropical Ultisols in Yunnan Province, China. Agr. Ecosyst.

Environ. 104 (2), 343–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2004.01.034.

Blanco-Canqui, H., Gantzer, C.J., Anderson, S.H., Alberts, E.E., Thompson, A.L., 2004. Grass barrier and vegetative filter strip effectiveness in reducing runoff, sediment,

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

nitrogen, and phosphorus loss. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 68 (5), 1670–1678. https://doi. org/10.2136/sssaj2004.1670.

Borrelli, P., Robinson, D.A., Fleischer, L.R., Lugato, E., Ballabio, C., Alewell, C., Meusburger, K., Modugno, S., Schütt, B., Ferro, V., Bagarello, V., Oost, K.V.,

Montanarella, L., Panagos, P., 2017. An assessment of the global impact of 21st century land use change on soil erosion. Nat. Commun. 8 (1), 1–13. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41467-017-02142-7.

Cerd`a, A., Rodrigo-Comino, J., 2020. Is the hillslope position relevant for runoff and soil

loss activation under high rainfall conditions in vineyards? Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 20 (1), 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecohyd.2019.05.006.

Cerd`a, A., Rodrigo-Comino, J., Gim´enez-Morera, A., Keesstra, S.D., 2018. Hydrological

and erosional impact and farmer’s perception on catch crops and weeds in citrus organic farming in Canyoles river watershed, Eastern Spain. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 258, 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2018.02.015.

Chen, J., Xiao, H.B., Li, Z.W., Liu, C., Ning, K., Tang, C.J., 2020. How effective are soil and water conservation measures (SWCMs) in reducing soil and water losses in the red soil hilly region of China? A meta-analysis of field plot data. Sci. Total Environ. 735, 139517 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139517.

Chen, H., Zhang, X.P., Abla, M., Lü, D., Yan, R., Ren, Q.F., Ren, Z.Y., Yang, Y.H., Zhao, W. H., Lin, P.F., Liu, B.Y., Yang, X.H., 2018. Effects of vegetation and rainfall types on

surface runoff and soil erosion on steep slopes on the Loess Plateau, China. Catena 170, 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2018.06.006.

Dagnew, D.C., Guzman, C.D., Zegeye, A.D., Tibebu, T.Y., Getaneh, M., Abate, S., Zemale, F.A., Ayana, E.K., Tilahun, S.A., Steenhuis, T.S., 2015. Impact of conservation practices on runoff and soil loss in the sub-humid Ethiopian Highlands:

The Debre Mawi watershed. J. Hydrol. Hydromech. 63 (3), 210–219. https://doi.

Dai, C.T., Liu, Y.J., Wang, T.W., Li, Z.X., Zhou, Y.W., 2018. Exploring optimal measures to reduce soil erosion and nutrient losses in southern China. Agr. Water Manag. 210,

41–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2018.07.032.

de Lima, J.L.M.P., Singh, V.P., de Lima, M.I.P., 2003. The influence of storm movement on water erosion: Storm direction and velocity effects. Catena 52 (1), 39–56. https:// doi.org/10.1016/S0341-8162(02)00149-2.

dos Santos, J.C.N., de Andrade, E.M., Medeiros, P.H.A., Guerreiro, M.J.S., de Queiroz Pala´cio, H.A., 2017. Effect of rainfall characteristics on runoff and water erosion for different land uses in a tropical semiarid region. Water Resour. Manag. 31, 173–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-016-1517-1.

Duan, J., Liu, Y.J., Yang, J., Tang, C.J., Shi, Z.H., 2020. Role of groundcover management in controlling soil erosion under extreme rainfall in citrus orchards of southern China. J. Hydrol. 582, 124290 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2019.124290.

Erkossa, T., Wudneh, A., Desalegn, B., Taye, G., 2015. Linking soil erosion to on-site

financial cost: lessons from watersheds in the Blue Nile basin. Solid Earth 6, 765–774. https://doi.org/10.5194/se-6-765-2015.

Fang, H.Y., Cai, Q.G., Chen, H., Li, Q.Y., 2008. Effect of rainfall regime and slope on

runoff in a gullied loess region on the Loess Plateau in China. Environ. Manag. 42 (3), 402–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-008-9122-6.

Fang, N.F., Wang, L., Shi, Z.H., 2017. Runoff and soil erosion of field plots in a

subtropical mountainous region of China. J. Hydrol. 552, 387–395. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2017.06.048.

Girmay, G., Singh, B.R., Nyssen, J., Borrosen, T., 2009. Runoff and sediment-associated nutrient losses under different land uses in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. J. Hydrol. 376

(1–2), 70–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2009.07.066.

Grum, B., Assefa, D., Hessel, R., Woldearegay, K., Kessler, C.A., Ritsema, C.J., Geissen, V.,

2017. Effect of in situ water harvesting techniques on soil and nutrient losses in semi- arid northern Ethiopia. Land Degrad. Dev. 28 (3), 1016–1027. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/ldr.2603.

Guadie, M., Molla, E., Mekonnen, M., Cerda`, A., 2020. Effects of soil bund and stone- faced soil bund on soil physicochemical properties and crop yield under rain-fed conditions of northwest Ethiopia. Land 9 (1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ land9010013.

Haileslassie, A., Priess, J., Veldkamp, E., Teketay, D., Lesschen, J.P., 2005. Assessment of soil nutrient depletion and its spatial variability on smallholders’ mixed farming systems in Ethiopia using partial versus full nutrient balances. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 108 (1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2004.12.010.

Han, J.Q., Ge, W.Y., Hei, Z., Cong, C.Y., Ma, C.L., Xie, M.X., Liu, B.Y., Feng, W., Wang, F.,

Jiao, J.Y., 2020. Agricultural land use and management weaken the soil erosion induced by extreme rainstorms. Agric., Ecosyst. Environ. 301, 107047 https://doi. org/10.1016/j.agee.2020.107047.

He, B.H., Chen, J.J., Xiang, M.H., Chen, Y., 2016. Effects of Vetiveria zizanioides and

Leucaena leucocephala hedgerows in different life-phases on soil erosion and organic matter of purple soil. Ecol. Environ. Monit. Three Gorges. 1 (1), 36–45. https://doi. org/10.3969/j.issn.2096-2347.2016.01.006.

Huang, G.Q., 2017. Problems and countermeasures of sustainable development of agricultural ecosystem in Southern China. Chin. J. Eco-Agr. 25 (1), 13–18. https:// doi.org/10.13930/j.cnki.cjea.160658.

Huang, G.Q., Zhao, Q.G., 2014. Initial exploration of red soil ecology. Acta Ecol. Sin. 34 (18), 5173–5181. https://doi.org/10.5846/stxb201405100944.

Huang, Z.G., Ouyang, Z.Y., Li, F.R., Zheng, H., Wang, X.K., 2010. Response of runoff and soil loss to reforestation and rainfall type in red soil region of southern China.

J. Environ. Sci. 22 (11), 1765–1773. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1001-0742(09)

Huo, J.Y., Yu, X.X., Liu, C.J., Chen, L.H., Zheng, W.G., Yang, Y.H., Tang, Z.X., 2020.

Effects of soil and water conservation management and rainfall types on runoff and soil loss for a sloping area in North China. Land Degrad. Dev. 31 (15), 2117–2130. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.3584.

Jiao, J.Y., Wang, W.Z., Hao, X.P., 1999. Precipitation and erosion characteristics of rain-

storm in different pattern on Loess Plateau. J. Arid. Land. Resour. Environ. 13 (1), 38–42. https://doi.org/10.1088/0256-307X/15/12/025.

Keesstra, S., Mol, G., de Leeuw, J., Okx, J., Molenaar, C., de Cleen, M., Visser, S., 2018. Soil-related sustainable development goals: four concepts to make land degradation neutrality and restoration work. Land 7 (4), 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/ land7040133.

Keesstra, S.D., Bouma, J., Wallinga, J., Tittonell, P., Smith, P., Cerda`, A., Montanarella, L., Quinton, J.N., Pachepsky, Y., van der Putten, W.H., Bardgett, R.D., Moolenaar, S., Mol, G., Jansen, B., Fresco, L.O., 2016a. The significance of soils and

soil science towards realization of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Soil 2, 111–128. https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-2-111-2016.

Keesstra, S., Pereira, P., Novara, A., Brevik, E.C., Azorin-Molina, C., Parras-Alc´antara, L.,

Jorda´n, A., Cerda`, A., 2016b. Effects of soil management techniques on soil water erosion in apricot orchards. Sci. Total Environ. 551–552, 357–366. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.01.182.

Keesstra, S.D., Rodrigo-Comino, J., Novara, A., Gim´enez-Morera, A., Pulido, M., Di Prima, S., Cerd`a, A., 2019. Straw mulch as a sustainable solution to decrease runoff

and erosion in glyphosate-treated clementine plantations in Eastern Spain. An assessment using rainfall simulation experiments. Catena 174, 95–103. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.catena.2018.11.007.

Kinnell, P.I.A., 2005. Raindrop-impact-induced erosion processes and prediction: a review. Hydrol. Process. 19 (14), 2815–2844. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.5788.

Kothyari, B.P., Verma, P.K., Joshi, B.K., Kothyari, U.C., 2004. Rainfall-runoff-soil and nutrient loss relationships for plot size areas of bhetagad watershed in Central

Himalaya, India. J. Hydrol. 293 (1–4), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

Li, T., Chen, Y., He, B.H., Xiang, M.H., Tang, H., Liu, X.H., Wang, R.Z., 2019. Study on soil and water conservation effects of Vetiveria zizanioides and Leucaena leucocephala hedgerows with different planting years in central hill region of Sichuan Basin.

J. Soil Water Conserv. 33 (3), 27–35 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI: CNKI:

Liang, Y., Li, D.C., Lu, X.X., Yang, X., Pan, X.Z., Mu, H., Shi, D.M., Zhang, B., 2010. Soil

erosion changes over the past five decades in the red soil region of Southern China. J. Mt. Sci. 7 (1), 92–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-010-1052-0.

Lo´pez-Vicente, M., Calvo-Seas, E., A´lvarez, S., Cerd`a, A., 2020. Effectiveness of cover

crops to reduce loss of soil organic matter in a rainfed vineyard. Land 9 (7), 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9070230.

Liu, Y.J., Yang, J., Hu, J.M., Tang, C.J., Zheng, H.J., 2016. Characteristics of the surface- subsurface flow generation and sediment yield to the rainfall regime and land-cover by long-term in-situ observation in the red soil region, Southern China. J. Hydrol.

539, 457–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2016.05.058.

Mayor, A.G., Bautista, S., Llovet, J., Bellot, J., 2007. Post-fire hydrological and erosional responses of a Mediterranean landscpe: seven years of catchment-scale dynamics.

Catena 71 (1), 68–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2006.10.006.

Mchugh, O.V., Steenhuis, T.S., Abebe, B., Fernandes, E.C.M., 2007. Performance of in situ rainwater conservation tillage techniques on dry spell mitigation and erosion

control in the drought-prone North Wello zone of the Ethiopian highlands. Soil . Res. 97 (1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2007.08.002.

Mekonnen, M., Keesstra, S.D., Baartman, J.E.M., Stroosnijder, L., Maroulis, J., 2017. Reducing sediment connectivity through man-made and natural sediment sinks in

the Minizr Catchment, Northwest Ethiopia. Land Degrad. Dev. 28 (2), 708–717.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.2629.

Mekonnen, M., Keesstra, S.D., Stroosnijder, L., Baartman, J.E.M., Maroulis, J., 2015. Soil

conservation through sediment trapping: a review. Land Degrad. Dev. 26 (6), 544–556. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.2308.

Moges, A., Hailu, W., Yimer, F., 2012. The Effects of “Fanya juu” soil conservation

structure on selected soil physical & chemical properties: the case of Goromti watershed, western Ethiopia. Res. Environ. 2 (4), 132–140. https://doi.org/ 10.5923/j.re.20120204.02.

Nearing, M.A., Xie, Y., Liu, B.Y., Ye, Y., 2017. Natural and anthropogenic rates of soil erosion. Int. Soil Water Conserv. 5 (2), 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. iswcr.2017.04.001.

Ngetich, K.F., Diels, J., Shisanya, C.A., Mugwe, J.N., Mucheru-Muna, M., Mugendi, D.N., 2014. Effects of selected soil and water conservation techniques on runoff, sediment yield and maize productivity under sub-humid and semi-arid conditions in Kenya.

Catena 121, 288–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2014.05.026.

Novara, A., Cerda, A., Barone, E., Gristina, L., 2021. Cover crop management and water conservation in vineyard and olive orchards. Soil Tillage Res. 208, 104896 https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2020.104896.

Peng, T., Wang, S.J., 2012. Effects of land use, land cover and rainfall regimes on the surface runoff and soil loss on karst slopes in southwest China. Catena 90, 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2011.11.001.

Prosdocimi, M., Burguet, M., Prima, S.D., Sofia, G., Terol, E., Rodrigo-Comino, J., Cerda`, A., Tarolli, P., 2017. Rainfall simulation and Structure-from-Motion photogrammetry for the analysis of soil water erosion in Mediterranean vineyards.

Sci. Total Environ. 574, 204–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.09.036.

Qin, W., Zuo, C.Q., Yan, Q.H., Wang, Z.Y., Du, P.F., Yan, N., 2015. Regularity of

individual rainfall soil erosion in bare slope land of red soil. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 31 (2), 124–132. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-6819.2015.02.018.

Ran, Q.H., Su, D.Y., Li, P., He, Z.G., 2012. Experimental study of the impact of rainfall characteristics on runoff generation and soil erosion. J. Hydrol. 424–425, 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2011.12.035.

Renard, K., Foster, G., Weesies, G., McCool, D., Yoder, D., 1997. Predicting soil erosion by water. A guide to conservation planning with the revised universal soil loss

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() equation (RUSLE). U. S. Dep. Agric., Agric. Res. Serv., Agric. Handb. (No. 703) http://handle.nal.usda.gov/10113/11126 .

equation (RUSLE). U. S. Dep. Agric., Agric. Res. Serv., Agric. Handb. (No. 703) http://handle.nal.usda.gov/10113/11126 .

Rodrigo-Comino, J., Terol, E., Mora, G., Gim´enez-Morera, A., Cerd`a, A., 2020. Vicia

sativa Roth. can reduce soil and water losses in recently planted vineyards (Vitis vinifera L.). Earth Syst. Environ. 4, 827–842. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41748-020- 00191-5.

Rodrigo-Comino, J., Keesstra, S.D., Cerda`, A., 2018. Connectivity assessment in Mediterranean vineyards using improved stock unearthing method, LiDAR and soil

erosion field surveys. Earth Surf. Proc. Land 43 (10), 2193–2206. https://doi.org/

Shi, Z.H., Huang, X.D., Ai, L., Fang, N.F., Wu, G.L., 2014. Quantitative analysis of factors

controlling sediment yield in mountainous watersheds. Geomorphology 226, 193–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2014.08.012.

Shui, J.G., Chai, X.Z., Zhang, R.L., 2001. Water and soil loss in different ecological models on sloping land of red soil. J. Soil. Water Conserv. 15 (2), 33–36. https://doi. org/10.13870/j.cnki.stbcxb.2001.02.009.

Sudhishri, S., Dass, A., Lenka, N.K., 2008. Efficacy of vegetative barriers for rehabilitation of degraded hill slopes in eastern India. Soil . Res. 99 (1), 98–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2008.01.004.

Teressa, D., 2017. The effectiveness of stone bund to maintain soil physical and chemical

![]() properties: the case of Weday watershed, east hararge zone, oromia, Ethiopia. Civ. Environ. Res. 9 (12), 9–18. https://core.ac.uk/reader/234678633 .

properties: the case of Weday watershed, east hararge zone, oromia, Ethiopia. Civ. Environ. Res. 9 (12), 9–18. https://core.ac.uk/reader/234678633 .

Teshome, A., de Graaff, J., Kassie, M., 2016. Household-level determinants of soil and

water conservation adoption phases: evidence from north-western Ethiopian highlands. Environ. Manag. 57 (3), 620–636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-015-

Truman, C.C., Strickland, T.C., Potter, T.L., Franklin, D.H., Bosch, D.D., Bednarz, C.W., 2007. Variable rainfall intensity and tillage effects on runoff, sediment, and carbon

losses from a loamy sand under simulated rainfall. J. Environ. Qual. 36 (5), 1495–1502. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2006.0018.

Tu, A.G., Xie, S.H., Li, Y., Nie, X.F., Mo, M.H., 2018. Dynamic characteristics of soil and water loss under long-term experiment in citrus orchard on red soil slope. J. Soil.

Water Conserv. 32 (2), 160–165. https://doi.org/10.13870/j.cnki.

van Dijk, A.I.J.M., Bruijnzeel, L.A., Rosewell, C.J., 2002. Rainfall intensity-kinetic energy relationships: a critical literature appraisal. J. Hydrol. 261 (1–4), 1–23. https://doi. org/10.1016/S0022-1694(02)00020-3.

Wang, L.J., Zhang, G.H., Wang, X., Li, X.Y., 2019. Hydraulics of overland flow influenced by litter incorporation under extreme rainfall. Hydrol. Process. 33 (5), 737–747. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.13358.

Wei, W., Chen, L.D., Fu, B.J., Huang, Z.L., Wu, D.P., Gui, L.D., 2007. The effect of land uses and rainfall regimes on runoff and soil erosion in the semi-arid loess hilly area,

China. J. Hydrol. 335 (3–4), 247–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

Wei, W., Chen, L.D., Fu, B.J., Lü, Y.H., Gong, J., 2009. Responses of water erosion to

rainfall extremes and vegetation types in a loess semiarid hilly area, NW China. Hydrol. Process. 23 (12), 1780–1791. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.7294.

Wei, W., Jia, F.Y., Yang, L., Chen, L.D., Zhang, H.D., Yu, Y., 2014. Effects of surficial condition and rainfall intensity on runoff in a loess hilly area, China. J. Hydrol. 513,

115–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2014.03.022.

Xie, T.S., Xie, S.C., Zhao, L., Yang, A.Q., 2015. Experiment of planting effect on ridge

hayrick field in sloping farmland of red soil and low hilly land. J. Water Resour. Water Eng. 26 (6), 220–224. https://doi.org/10.11705/j.issn.1672- 643X.2015.06.41.

Yang, J., Zheng, H.J., Chen, X.A., Shen, L., 2013. Effects of tillage practices on nutrient loss and soybean growth in red-soil slope farmland. Int. Soil Water Conserv. 1 (3),

49–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2095-6339(15)30030-7.

Zhang, L.M., Lin, J.S., Yu, D.S., Shi, X.Z., 2011. Relationship between sediment yield and rainfall factors on various soils of southern China. Bull. Soil. Water Conserv. 31 (2),

10–14. https://doi.org/10.13961/j.cnki.stbctb.2011.02.029.

Zhao, L.S., Hou, R., Wu, F.Q., Keesstra, S., 2018. Effect of soil surface roughness on

infiltration water, ponding and runoff on tilled soils under rainfall simulation experiments. Soil . Res. 179, 47–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2018.01.009.

Zheng, H.J., Li, H.R., Mo, M.H., Song, Y.J., Liu, Z., Zhang, H.M., 2021. Quantified