我国黄土高原夏季玉米树冠特点和用水效率的响应

![]()

Agricultural Water Management 254 (2021) 106948

Agricultural Water Management 254 (2021) 106948

![]()

Responses of canopy characteristics and water use efficiency to ![]() ammoniated straw incorporation for summer maize (Zea mays L.) in the

ammoniated straw incorporation for summer maize (Zea mays L.) in the

Loess Plateau, China

Yue Li a, c, Ji Chen c, f, g, Hao Feng a, b, d,*, 1, Qin’ge Dong a, b, d,*, 1, Kadambot H.M. Siddique e

a College of Water Resources and Architectural Engineering, Northwest A&F University, Yangling 712100, Shaanxi, China

b Institute of Soil and Water Conservation, Chinese Academy of Sciences and Ministry of Water Resources, Yangling 712100, Shaanxi, China

c Aarhus University Centre for Circular Bioeconomy, Department of Agroecology, Aarhus University, 8830 Tjele, Denmark

d Institute of Water Saving Agriculture in Arid Areas of China, Northwest A&F University, Yangling 712100, Shaanxi, China

e The UWA Institute of Agriculture and School of Agriculture and Environment, The University of Western Australia, Perth, WA 6001, Australia

f Department of Agroecology, Aarhus University, 8830 Tjele, Denmark

g iCLIMATE Interdisciplinary Centre for Climate Change, Aarhus University, 4000 Roskilde, Denmark

![]()

A R T I C L E I N F O

![]() Handling Editor - Dr. B.E. Clothier

Handling Editor - Dr. B.E. Clothier

![]() Keywords:

Keywords:

Ammoniated straw incorporation Maize growth

Grain yield

Water use efficiency Loess Plateau

A B S T R A C T

![]()

Straw application has a wide range of environmental benefits that make it an effective practice for sustainable agriculture. However, little is well known about the impacts of ammoniated straw addition on soil water and crop canopy characteristics in maize cultivation systems. A 3-year field experiment of summer maize (Zea mays L.) in Northwest China was conducted to evaluate the effects of different straw applications on soil water storage, maize canopy growth, grain yield and water use efficiency (WUE). The three treatments were: (i) no straw (traditional tillage, CK), (ii) straw mulch (traditional straw returning, T1), and (iii) ammoniated straw incor- porated into the soil (optimized straw returning, T2). The T2 treatment increased average WUE by 14.8%, 7.8%, and 16.1% in 2016, 2017, and 2018, respectively, relative to the CK treatment. The 3-year average grain yield of the T2 treatment was 13.5% and 8.3% greater than grain yield of the CK and T1 treatments, respectively. Harvest index and 100-kernel weight of summer maize in the T2 treatment were higher than observed for the CK and T1 treatments. Across the three growing years, the T2 treatment was superior over the T1 and CK treatments in improving average LAI, spatial density of leaf area, green canopy cover and aboveground biomass. Hence, our study recommends that using ammoniated straw incorporation could be a promising application for synergis- tically improving maize growth, WUE and grain yield within this semi-arid region.

![]()

Globally larger areas may experience soil degradation and water scarcity with global warming (IPCC, 2013), which may be one of the most critical factors for limiting crop productivity in arid and semi-arid croplands. To meet the growing demands for food and bioenergy, sci- entists have been searching for ways to increase crop production in cropland systems (Battaglia et al., 2021). The Loess Plateau in China is a representative rainfed agricultural region, where maize (Zea mays L.) is one of the most popular crops (Bu et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2018). The main problems affecting crop productivity in this planting area are excessive fertilizer with low fertilizer use efficiency

(Chen et al., 2015), limited precipitation (Bai et al., 2009), and shortage of valid measures improving water and fertilization conservation (Bu et al., 2013). As such, there is a growing demand currently for finding effective measures to promote crop growth and increase soil water use efficiency.

Straw addition practices have ecological prospects because they can provide favorable soil conditions to benefit crop growth (Battaglia et al., 2021; Xia et al., 2018). Straw returning not only decreases the air pollution caused by straw burning, but also promotes soil fertility (K¨anka¨nen et al., 2011; Romic et al., 2003; Zhao et al., 2014). Compared with traditional tillage practices (e.g., only fertilizer added to the soil), straw application could increase crop production and improve soil water

![]()

* Corresponding authors at: College of Water Resources and Architectural Engineering, Northwest A&F University, Yangling 712100, Shaanxi, China.

E-mail addresses: nercwsi@vip.sina.com (H. Feng), qgdong2011@163.com (Q. Dong).

1 Current address: Institute of Soil and Water Conservation, Northwest A&F University, Yangling 712100, China.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2021.106948

Received 3 June 2020; Received in revised form 26 April 2021; Accepted 27 April 2021

Available online 13 May 2021

0378-3774/© 2021 Published by Elsevier B.V.

![]()

![]()

![]()

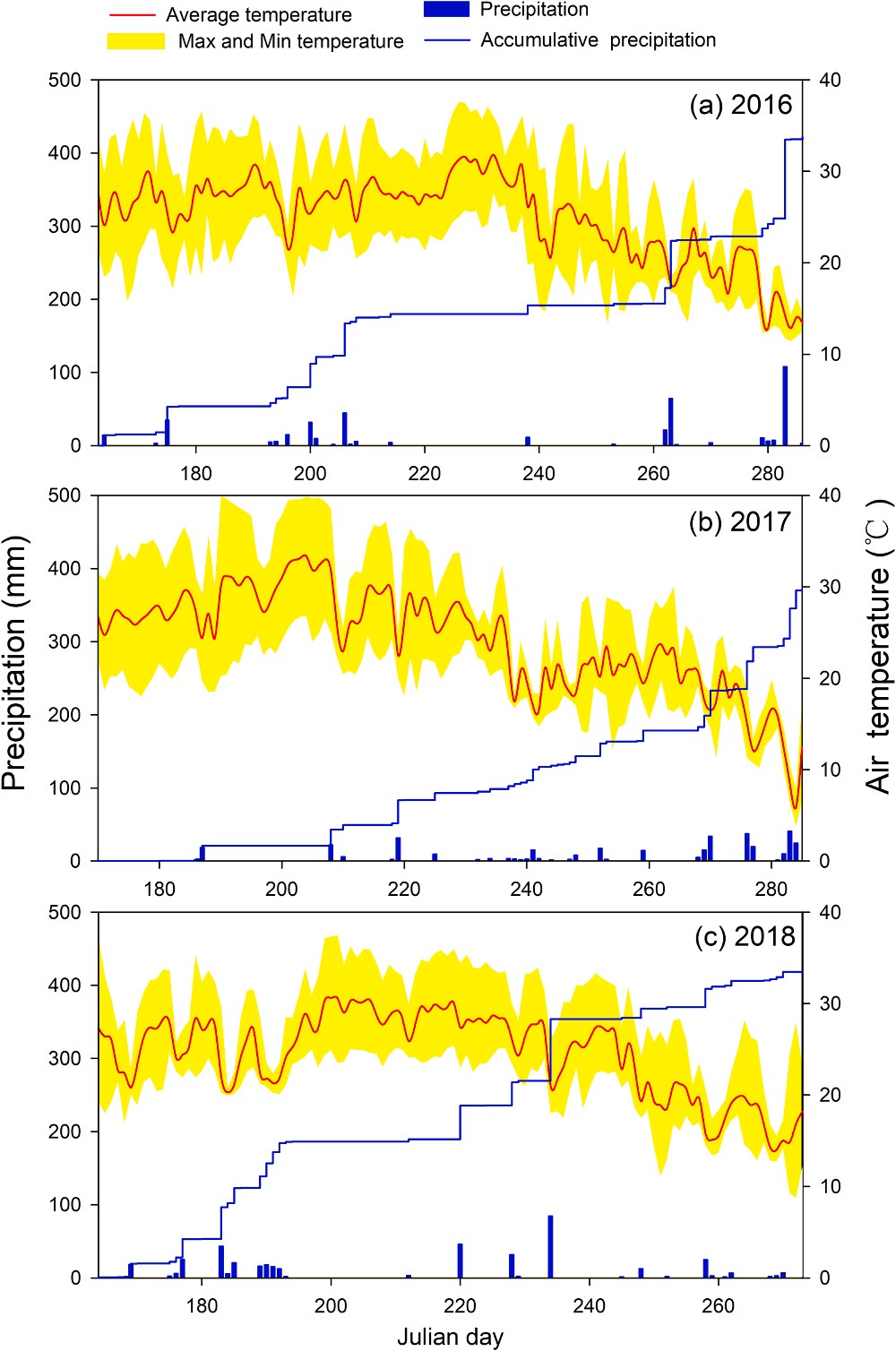

Fig. 1. Daily average temperature (solid red line), changes in daily maximum and minimum temperatures (yellow shade), accumulative precipitation (solid

Fig. 1. Daily average temperature (solid red line), changes in daily maximum and minimum temperatures (yellow shade), accumulative precipitation (solid

blue line), and daily precipitation (blue bars) during the 2016–2018 summer

maize growing seasons. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

storage (Wang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2021). Chen et al. (2007) re- ported that straw mulching can improve soil temperature (that is, keep the soil warmer in winter and cooler in summer) and decrease soil evaporation. Ram et al. (2013) stated that straw addition could increase grain yield because of the enhanced soil organic matter. However, there are lots of issues associated with straw utilization. One may be the nu- trients in the straw cannot be quickly absorbed and utilized by crops due to the slow decomposition (Cabiles et al., 2008; Yu et al., 2017). Another problem may be crop straw is usually used for household heating or grazing, resulting in resource waste (Liu et al., 2014). Therefore, there needs to be wiser straw management to establish new paradigms for better straw returning in the future.

Crop residue is a valuable natural source that can enhance soil nu- trients and increase crop yield (Liu et al., 2014; Xia et al., 2018). Different straw management practices could affect crop growth and grain yield by modifying soil nutrient status (Bhella, 1988; Parfitt and Stott, 1984). Ammoniated crop straw can be used as a food supplement for ruminant livestock (Mann et al., 1988). Cabiles et al. (2008) and Yu et al. (2017) reported that straw with low C/N ratios can improve soil fertility by accelerating nutrient release from the straw. Angers and Recous (1997) and Xia et al. (2018) reported that straw with different C/N ratios could affect straw characteristics (e.g., straw hemicellulose, straw lignin and straw crude protein content), which may affect straw decomposition. Li et al. (2020) and Zou et al. (2020) demonstrated that

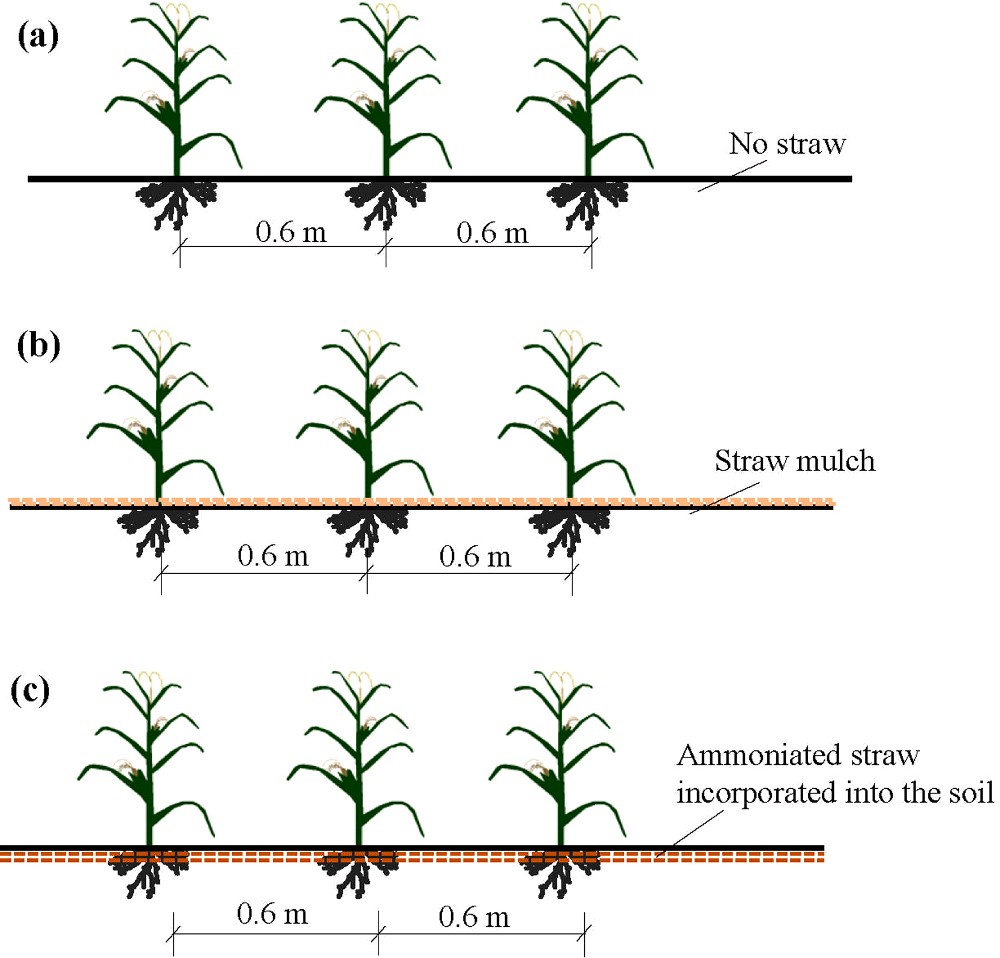

Fig. 2. Schematic diagram of the experimental system for summer maize. (a) CK, no straw (traditional tillage); (b) T1, straw mulch (traditional straw returning); and (c) T2, ammoniated straw incorporated into the soil (optimized straw returning).

ammoniated straw returning could promote grain yield. In semi-arid areas, agronomic management practices, such as straw application, which could increase soil moisture and reduce crop water losses (Fran- zluebbers, 2002; Singh et al., 1993). However, less attention has been simultaneously paid to the effects of ammoniated crop straw on maize growth and soil water in semi-arid croplands.

Optimizing straw application that aims to improve crop growth, in- crease crop production and promote water use efficiency (WUE) should be strongly pursued. However, few studies have simultaneously focused on the effects of ammoniated crop straw on soil water content, canopy characteristics of summer maize (e.g., leaf rolling index, leaf erection index and spatial density of leaf area), aboveground biomass, grain yield and WUE. Based on the previous studies, we hypothesized that ammo- niated straw incorporation could improve maize growth to increase aboveground biomass and grain yield compared to the traditional straw addition. We also hypothesized that ammoniated straw addition could increase soil water content and WUE compared to straw mulch. There- fore, our aims were to explore the effects of ammoniated straw incor- poration and straw mulch on (1) changes in canopy characteristics of summer maize at different growth stages across the 3 years, and (2) soil water storage, grain yield and WUE over the 3 years.

2.1. Experiment site description

A 3-year field experiment was conducted at Northwest A&F Uni- versity (34◦ 20′ N, 108◦ 24′ E, 521 m) in Yangling, China. This region has

warm temperatures and a monsoon climate. The soil texture is silty loam

![]() (silt: sand: clay 75: 8: 17), and the 0–20 cm topsoil has an average soil bulk density of 1.45 g cm–3, pH of 8.4, a field water capacity of

(silt: sand: clay 75: 8: 17), and the 0–20 cm topsoil has an average soil bulk density of 1.45 g cm–3, pH of 8.4, a field water capacity of

23–25% (volumetric), and permanent wilting water content of 8.5%. The frost-free period and total annual sunshine hours are about 220 days and 2196 h, respectively. Meteorological data during the summer maize

growing seasons were collected from an automatic weather station (HOBO event logger, USA) located in a nearby experimental field (Fig. 1).

![]()

![]()

![]()

Crop information for summer maize (Zea mays L.) at the experimental site.

Year Variety Date of operation Fertilization date Fertilization rate

![]()

![]() Sowing date Harvest date

Sowing date Harvest date

2016 Qinlong 14 16–Jun 12–Oct 15 June 2016 P: 54 kg ha–1, N: 120 kg ha–1

2017 19–Jun 12–Oct 18 June 2017

![]()

2018 13–Jun 30–Sep 12 June 2018

![]()

2.2. Field experimental design

The experiment was conducted during the 2016, 2017 and 2018 summer maize growing seasons. The three treatments, each with three replicates, comprised a flat panting system with: (i) no straw (CK), (ii)

LAI = A⋅ρ⋅10—4 (3)

GCC = 1.005 × (1 — exp—0.6×LAI )1.2 (4)

LAI

straw mulch (traditional straw returning, T1), and (iii) ammoniated straw incorporated into the soil (optimized straw returning, T2) (Fig. 2).

SDA = H (5)

Each plot was 4 m wide by 5 m long. A 2 m maize buffer was planted to prevent marginal effects. The maize variety ‘Qinlong No.14’, widely grown by local farmers, was sown in rows 60 cm apart, with 30 cm spacing between plants. The amount of winter wheat straw returned to

the experiment field was 4000 kg ha—1, which was mechanically chop- ped into 5 cm lengths. Following typical local practices and general

recommendations, all plots received a basal fertilizer before sowing maize, with no top dressing during each growing season. Cropping in- formation at the experimental site is presented in Table 1.

2.3. Sampling and measurement

2.3.1. Soil water

During each summer maize growing season, the gravimetric water content to 100 cm depth was measured at the 3-leaf, jointing, tasseling,

grain filling and maturity stages. Soil samples were taken at 0–10, 10–20, 20–30, 30–40, 40–60, 60–80 and 80–100 cm depths using stainless steel cylinders (50 mm diameter) in triplicate, which were

oven-dried at 105 ◦C to determine soil water content. Before sowing and after harvesting time, soil water content (10 cm intervals from 0 to 100 cm) was measured to determine changes in soil water storage (SWS, mm) in the soil profile throughout the summer maize growing season. Extra measurements were also taken before and after precipitation.

Soil water storage was calculated using Eq. (1):

where ρ is plant density (plants ha–1), A is total leaf area of a single maize plant (m2), and H is maize plant height (cm), respectively.

The maize leaf natural length (Ln, cm), maximum leaf length (Lm, cm), leaf natural width (Wn, cm), and maximum leaf width (Wm, cm) were measured to calculate the leaf erection index (LEI, %) and leaf rolling index (LRI, %) using Eqs. (6) and (7) (Xiang et al., 2012):

2.3.3. Plant water content, aboveground biomass and grain yield

Three plants of summer maize from the central rows were cut close to the soil surface and weighed for determination of aboveground biomass at 3-leaf, jointing, tasseling, grain filling and maturity stages. And, fresh weight of maize plants was weighed after cutting, and dry weight of maize plants was determined after oven drying at 75 ◦C to constant weight. The plots were harvested manually on October 12, 2016, October 12, 2017 and September 30, 2018. And, grain yield and 100- kernel weights were recorded.

Plant water content (θ, %) was calculated using Eq. (8):

SWS = 10⋅h⋅a⋅b

(1) –1

100

where SWS is soil water storage (mm), h is soil depth (cm), a is soil density (g cm–3), and b is soil water content (%, wt/wt), respectively.

where Wf is fresh weight of aboveground biomass (g plant weight of aboveground biomass (g plant–1), respectively.

2.3.4. Evapotranspiration and water use efficiency

), Wd is dry

2.3.2. Leaf area, spatial density of leaf area, leaf rolling index and leaf erection index

Six representative maize plants were randomly selected for plant height and leaf area measurements at the 3-leaf, jointing, tasseling, grain filling and maturity stages in each growing season, which were manually measured using a tape. The maximum width and length of each maize

leaf was measured. The total leaf area per plant (A, m2) was estimated

using Eq. (2) (Mckee, 1964):

Evapotranspiration (ET, mm) was calculated using Eq. (9):

ET = (ΔSWS + I + P) — (R + D + C) (9)

where ∆SWS, I, P, R, D, and C represent changes in soil water storage (mm), irrigation (mm), precipitation (mm), surface runoff (mm), downward drainage out of the root zone (mm), and upward flow (mm), respectively. The groundwater table remained about 50 m below the surface, so the upward flow into roots was negligible. There were no heavy rains, irrigation applied or runoff observed (experimental field is flat) during the experiment period (thus, R, D, C, and I were zero) (Dong

i=1

where i is leaf number, Li is maximum leaf length (m), Wi is maximum leaf width (m), 0.75 is the correction coefficient for leaf shape,

et al., 2018; Li et al., 2020).

Water use efficiency (WUE, kg ha–1 were calculated as follows:

Y

mm–1) and harvest index (HI, %)

respectively.

–2 –2

WUE = ET (10)

Leaf area index (LAI, m m ), green canopy cover (GCC, %) and

![]()

![]()

spatial density of maize leaf area (SDA, cm–2 cm–3) for each plot were calculated using the following equations (Hsiao et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2017):

HI = Y (11)

![]() where Y is grain yield, kg ha–1; ET represents evapotranspiration, mm; B

where Y is grain yield, kg ha–1; ET represents evapotranspiration, mm; B

![]()

![]()

![]()

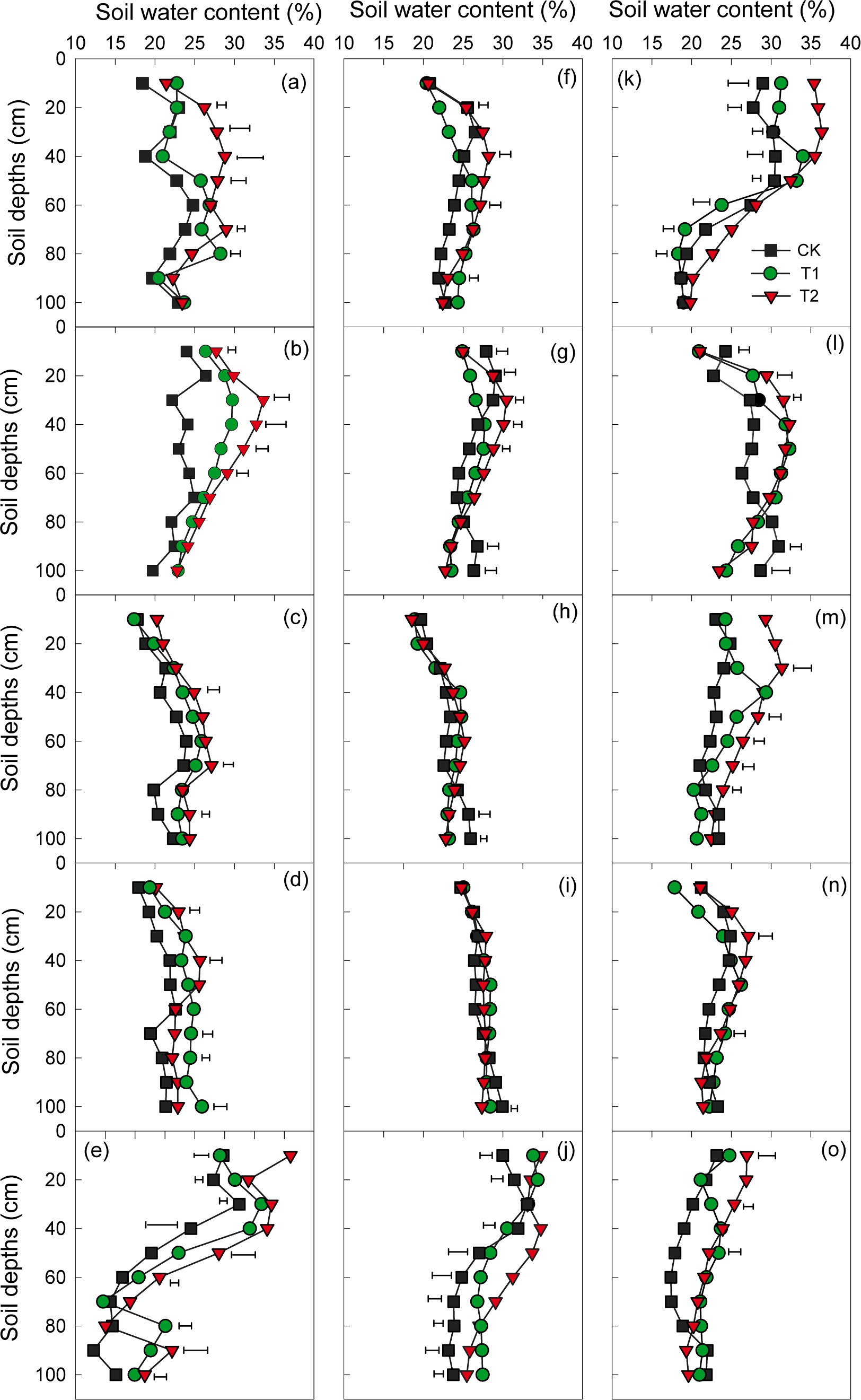

Fig. 3. Vertical distribution of gravimetric soil moisture under three treatments (CK, T1, and T2) in the 2016–2018 summer maize growing seasons. CK, no straw (traditional tillage); T1, straw mulch (traditional straw returning); T2, ammoniated straw incorporated into the soil (optimized straw returning). (a–e), (f–j), and (k–o) are the 3-leaf, jointing, tasseling, grain-filling, and maturity stages in the 2016, 2017, and 2018 summer maize growing seasons, respectively. Horizontal black bars indicate LSD at p = 0.05 (n = 3).

![]()

![]()

![]()

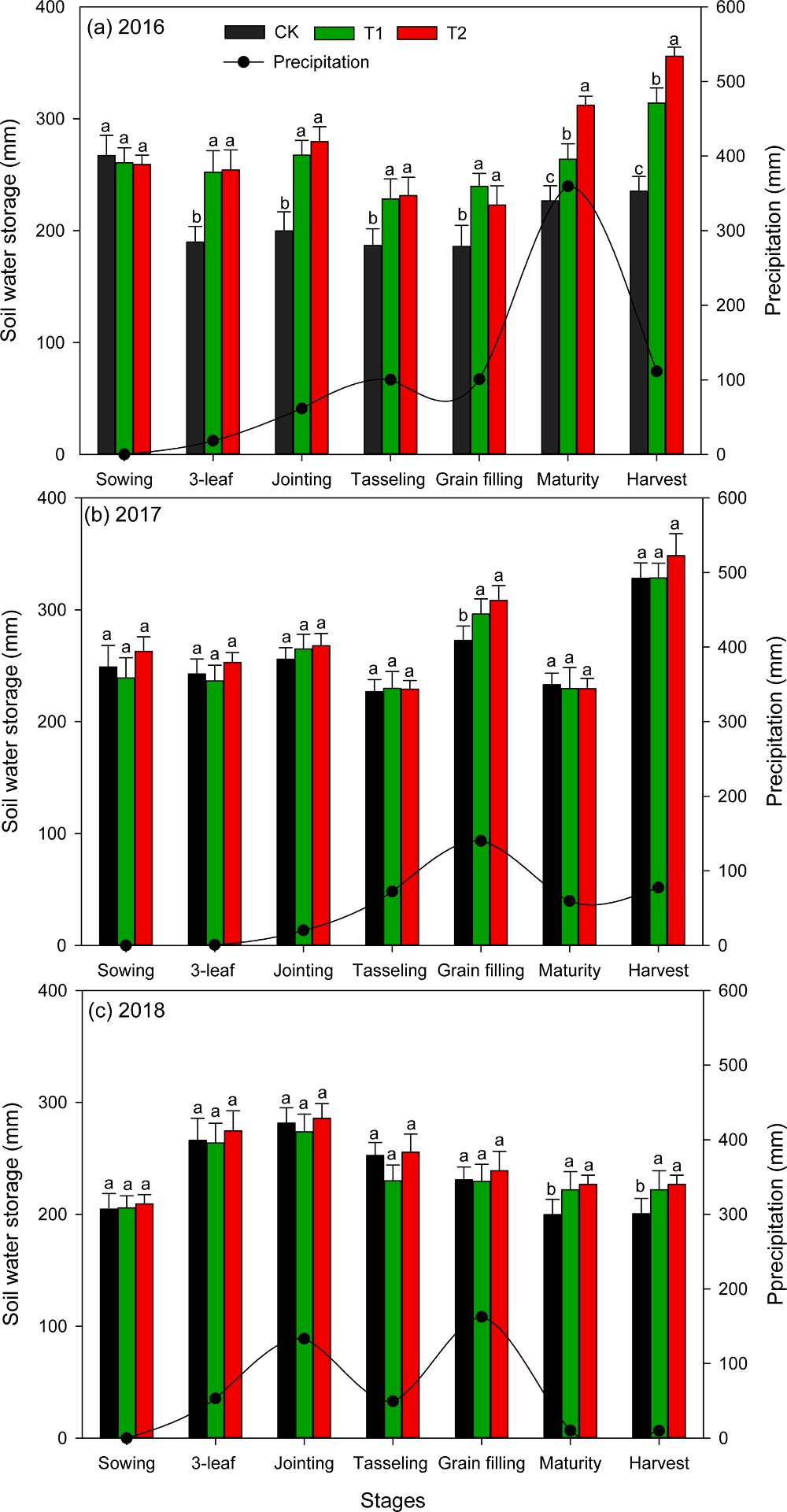

Fig. 4. Changes in soil water storage in the 0—100 cm soil layer under three treatments (CK, T1, and T2) in the 2016–2018 summer maize growing seasons. CK, no straw (traditional tillage); T1, straw mulch (traditional straw returning); T2, ammoniated straw incorporated into the soil (optimized straw returning). Vertical bars show mean ± SE (n = 3).

is aboveground biomass, kg ha–1, respectively.

2.4. Statistic analysis

All data were tested and analyzed using ANOVA in SPSS 20 (IBM, Inc.). The multiple comparisons of annual mean values were performed

using Duncan’s Multiple Range Test. Vertical changes in soil water content (0–100 cm soil layer) were tested with an LSD (least significant difference) means comparison test. A linear mixed-effects model (LME)

was used to test for differences in the interactions between maize growth

parameters (i.e., leaf rolling index, leaf erection index and spatial den- sity of leaf areas) between treatments (CK, T1, and T2), using the “nlme” package within R software (R Core Team, 2013). And, we set treatments, growth stages and their interactions as fixed effects, and the plot as random factor. All observations of growing years are put separately or

together for each summer maize growing year. To evaluate effects on grain yield, we set treatments and growing years as fixed effects, and the plot as random factor. And, to evaluate year effects on aboveground biomass and WUE for treatments, we set treatments as fixed effects, and the plot as random factor. All graphics were performed using R software (version 4.0.2) and Sigmaplot 12.5 (Sytat Software, Inc.).

3.1. Soil water

The significant effects on the soil water content were observed at 3- leaf stage in the three growing years (Fig. 3). During the 3-leaf stage, the T2 treatment had higher soil water content than the CK and T1 treat-

ments at 20–40 cm soil depth in 2016, 2017 and 2018 growing years

(p < 0.05). At the jointing stage in 2016 and 2017, the T2 treatment had lower soil water content than the CK treatment at 90–100 cm soil depth. At tasseling stage in 2018, the T2 treatment had significantly higher soil water content than the CK treatment at 20–60 cm soil depth. Across the three growing seasons, the average soil water contents within the 0–100 cm soil layer under the T1 (15.3%) and T2 (26.4%) treatments were higher than the CK treatment.

The results indicated that the T2 and T1 treatments generally enhanced soil water storage within the 0–100 cm soil layer compared to the CK treatment during the three growing seasons (Fig. 4). In 2016 and 2017, soil water storage (SWS) had the greatest values at the harvest

time, whereas in 2018 the highest SWS was observed at the jointing stage. In 2016, the precipitation was concentrated at the maturity stage. The SWS increased with the increased precipitation at maturity stage and harvest time. In 2017 and 2018, precipitation increased at grain filling stages and summer maize grew well with increased water con- sumption. The T2 and T1 treatments had 13.8% and 12.3% higher mean

soil water storage within the 0–100 cm soil layer than the CK treatment across the three maize growing seasons.

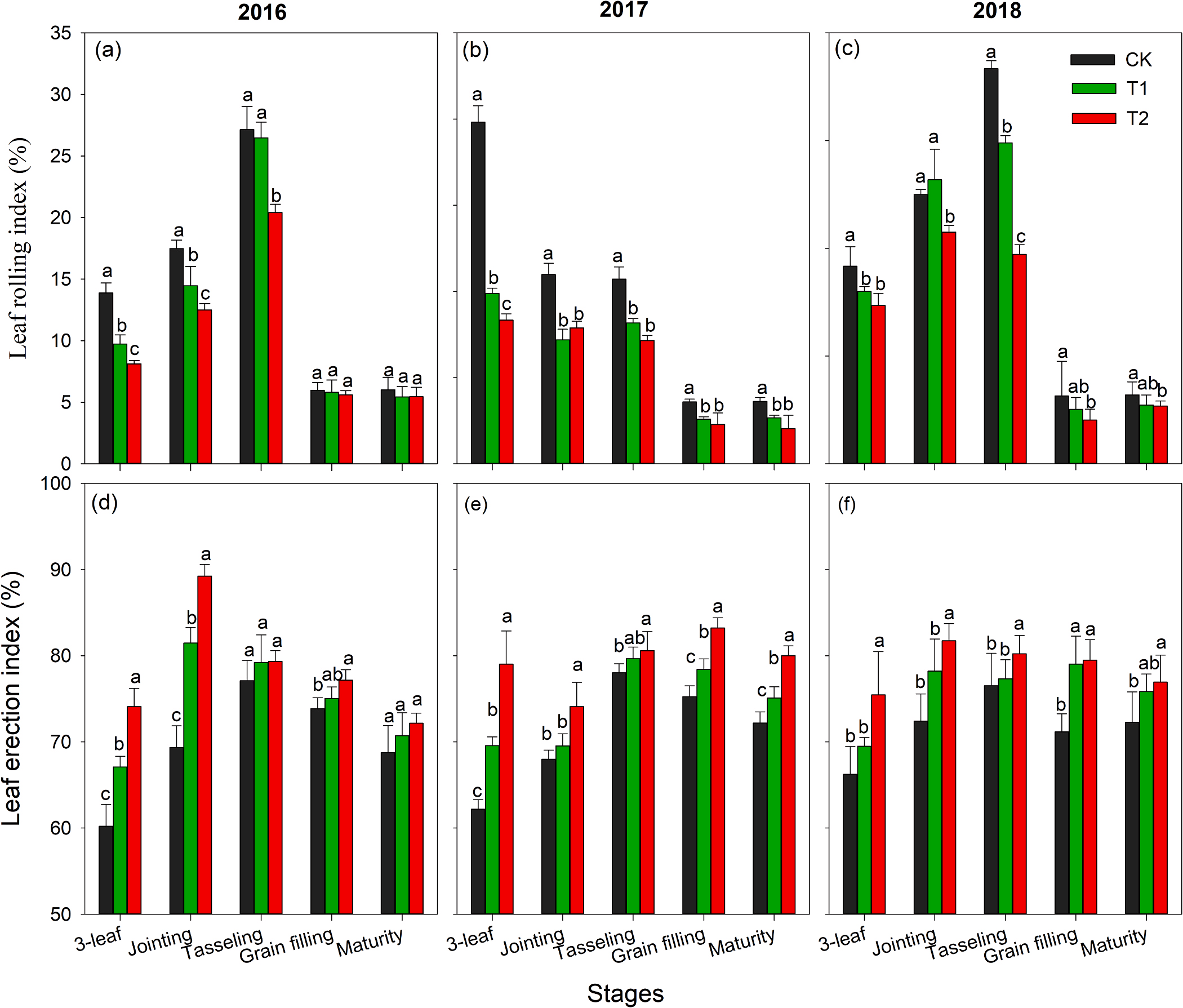

3.2. Maize growth

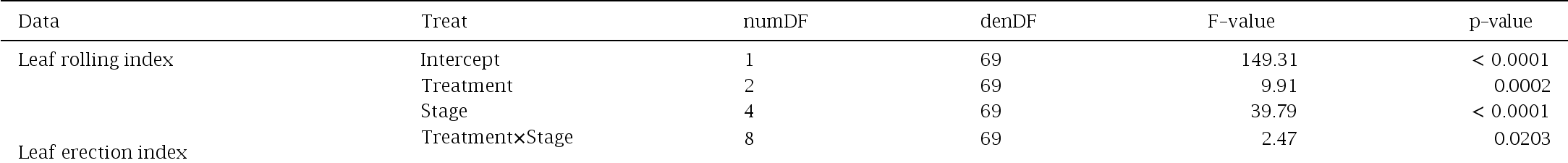

3.2.1. Leaf rolling index, leaf erection index and spatial density of leaf area Averaged across the 3 years, the T2 treatment decreased the leaf rolling index and increased the leaf erection index (Fig. 5). The average leaf rolling index was higher at early growth stages (3-leaf, jointing, and tasseling) than later growth stages (grain filling and maturity). Compared with the CK treatment, the T2 and T1 treatments decreased the leaf rolling index at each growth stage, with significant decreases observed during grain filling and at maturity. At the 3-leaf stage each year, the T2 treatment had lower leaf rolling index than the CK and T1 treatments. For the leaf erection index, the CK, T1, and T2 treatments were ranked as: T2 > T1 > CK. Changes in the leaf erection index generally followed consistent trends each year. The results of the linear mixed-effects model for treatments on leaf rolling index, leaf erection index, spatial density of leaf area and their interactions are summarized in Table 2. The treatments had significant effects on maize growth, i.e., there were significant interactions between leaf rolling index, leaf

erection index and spatial density of leaf area.

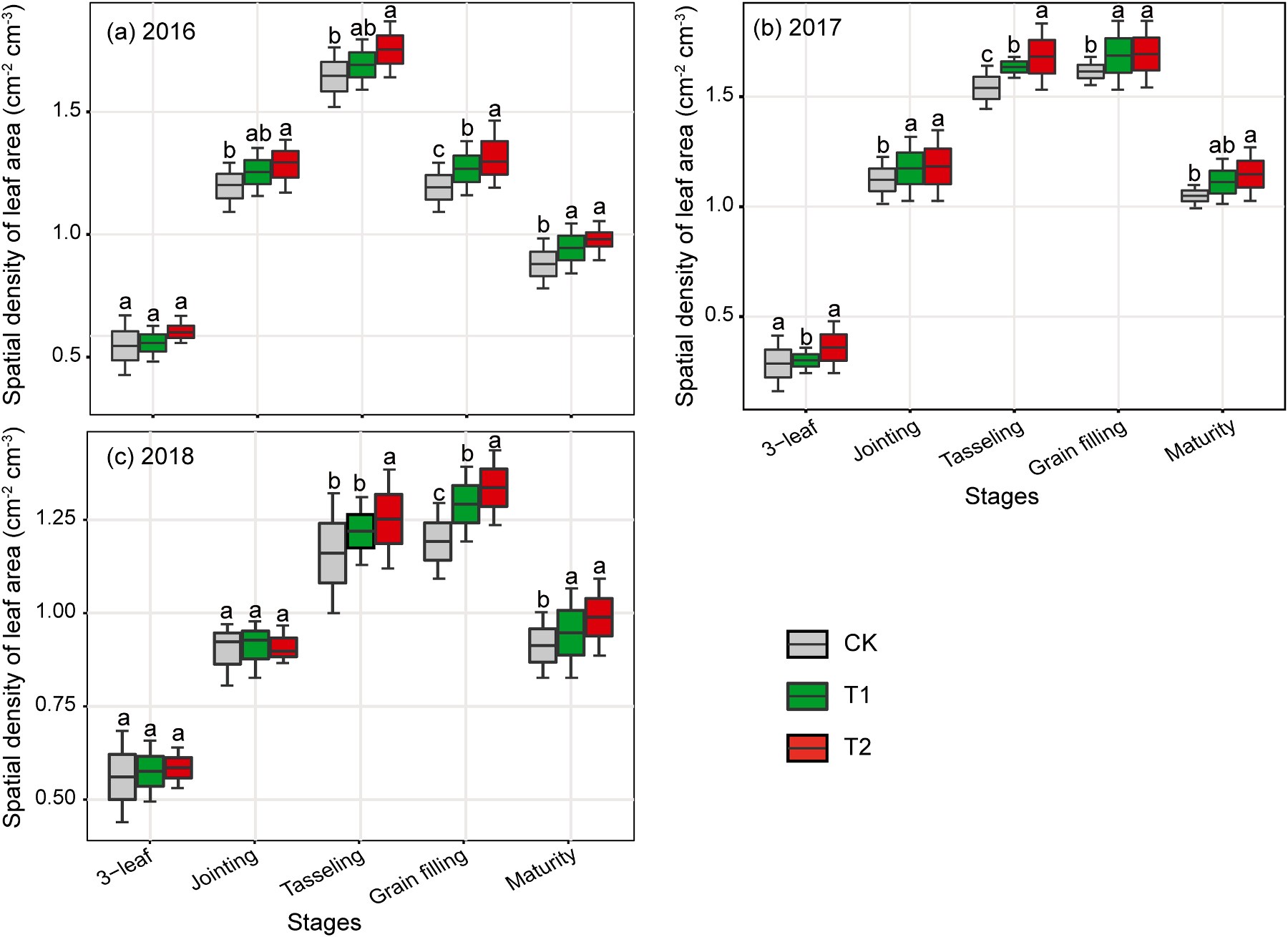

Seasonal fluctuations in the spatial density of leaf area, LAI, and plant height followed similar trends for each treatment in each year (Fig. 6, S1, and S2). Generally, the T2 treatment had a higher spatial density of leaf area than the CK and T1 treatments. For the CK, T1 and T2 treatments, the plant height and LAI of summer maize first increased and then decreased as growth proceeded during the 3 years of the study. Maximum plant height and LAI occurred at grain filling stage, after which plant height and LAI gradually decreased, as plants senesced (Figs. S1 and S2). The plant height and LAI values of the T2 treatment were significantly greater than those of the CK and T1 treatments.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Fig. 5. Changes in leaf rolling index and leaf erection index of summer maize at different growth stages in the 2016–2018 growing seasons. CK, no straw (traditional tillage); T1, straw mulch (traditional straw returning); T2, ammoniated straw incorporated into the soil (optimized straw returning). Different lowercase letters denote significant differences between treatments (n = 3).

![]()

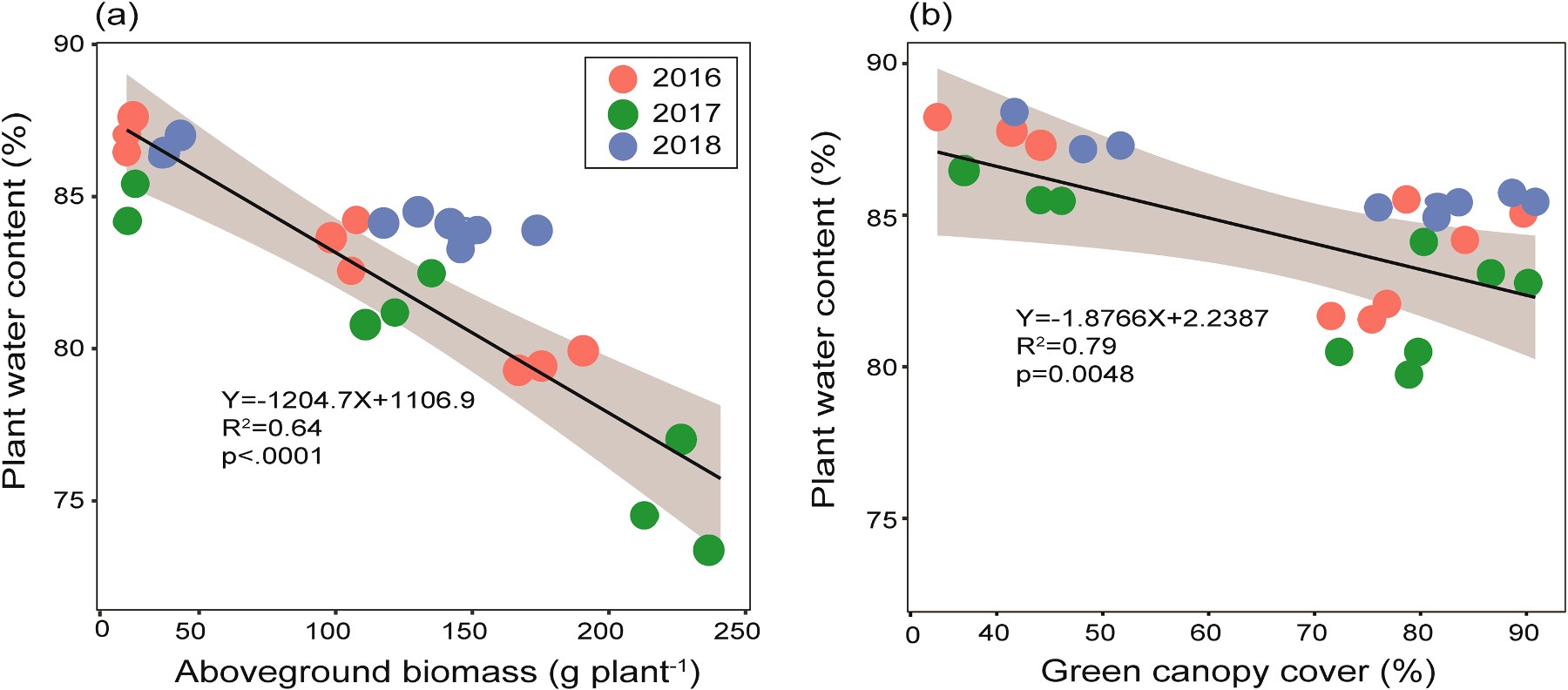

3.2.2. Green canopy cover, aboveground biomass and plant water content A negative relationship was found between average plant water content and aboveground biomass (Fig. 7a). Similarly, there is a nega- tive correlation between average plant content and green canopy cover

(Fig. 7b). Averaged across the 3 years (2016–2018), the T2 treatment

had higher green canopy cover compared to the T1 and CK treatments (Fig. S3). After the jointing stage, significant treatment effects occurred for green canopy cover. The T2 treatment had the highest green canopy cover at the grain filling stage, being 15.0%, 18.7%, and 13.3% higher than that of CK in 2016, 2017, and 2018, respectively. In addition, the T2 treatment had higher aboveground biomass, both fresh and dry, than the CK and T1 treatments at each growth stage in each year (Fig. S4).

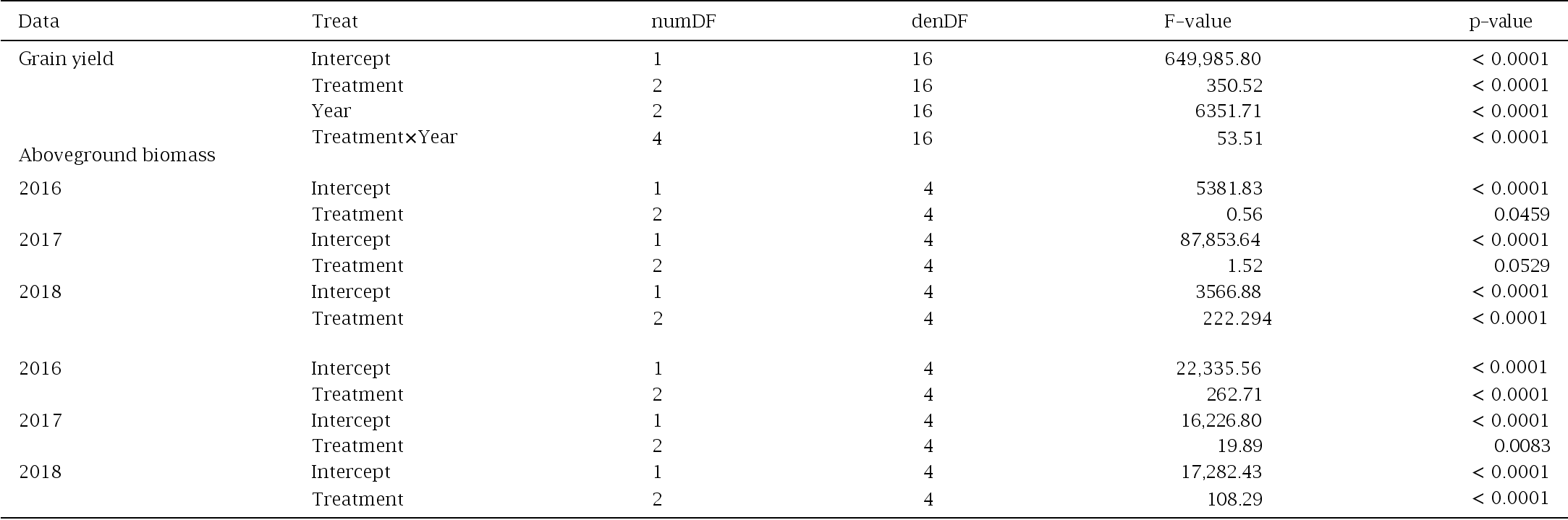

3.2.3. Grain yield, harvest index, evapotranspiration, and water use efficiency (WUE)

Grain yield and harvest index values are presented in Table 3. The T2 treatment had 5.9% and 3.9% higher grain yield than the CK and T1 treatment in 2016, 5.4% and 4.1% higher in 2017, and 13.4% and 8.9% higher in 2018, respectively. The T2 treatment had the highest harvest index and grain yield across the three seasons of summer maize. The

highest WUE was recorded under the T2 treatment than those values under the CK and T1 treatments. In addition, the T2 treatment had the lower ET values, and the CK treatment had the highest values. The T2 treatment had 5.8%, 7.7%, and 11.2% greater 100-kernel weight than the CK treatment, and the T1 treatment had 4.9%, 3.8%, and 5.6% greater 100-kernel weight than CK in 2016, 2017 and 2018 (Table 3), respectively. In the linear mixed-effects model, we found significant year effects for grain yield, aboveground biomass and WUE, and year effects were found for those values (Table 4).

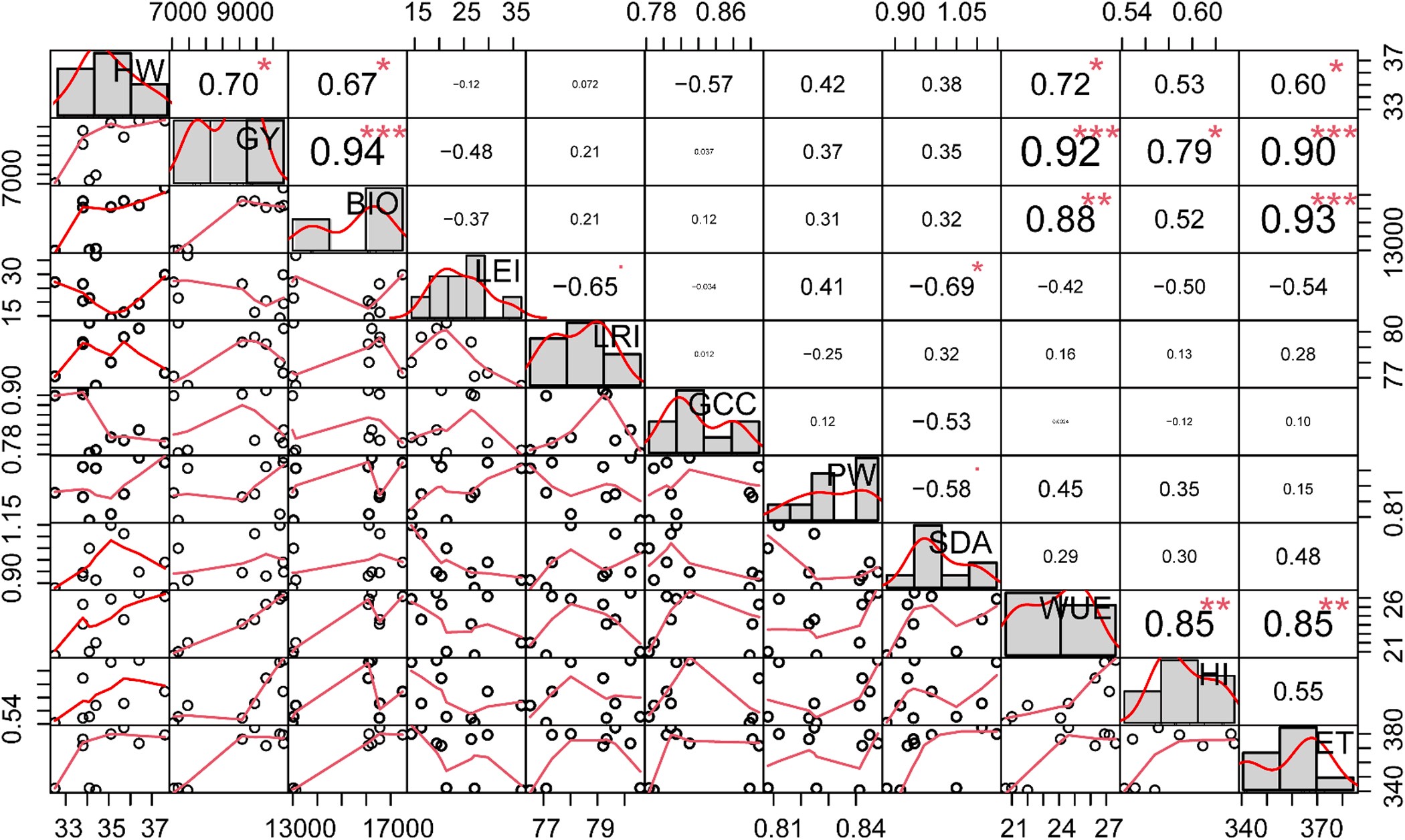

3.3. Correlations between 100-grain weight (HW), grain yield (GY), aboveground biomass (BIO), leaf rolling index (LEI), leaf erection index (LRI), green canopy cover (GCC), plant water (PW), spatial density of leaf areas (SDA), water use efficiency (WUE), harvest index (HI), and evapotranspiration (ET)

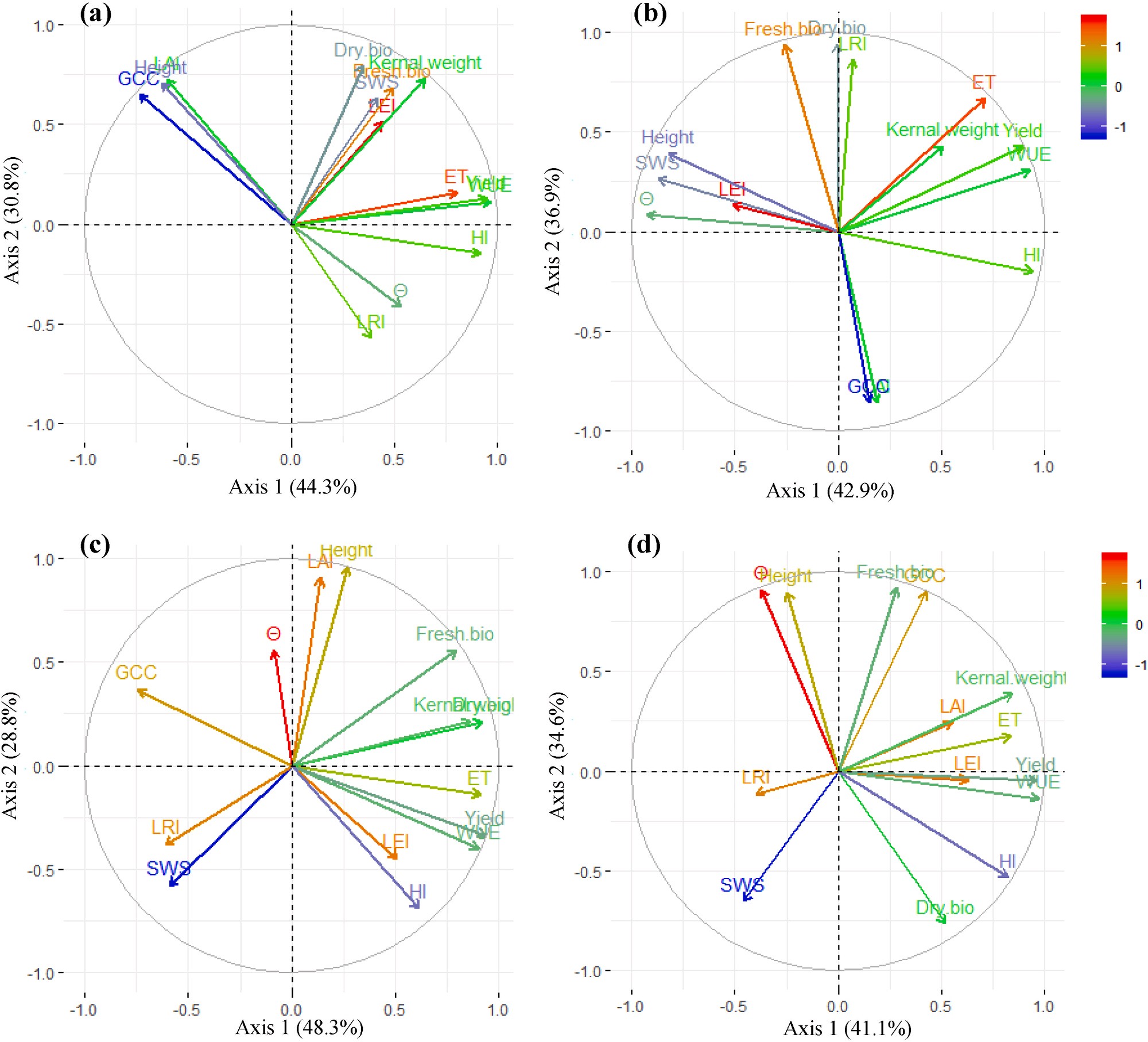

Based on the principal component analysis (PCA) on the indices of soil water and maize growth, the first two principal components accounted for 74.9%, 79.8%, 77.1%, and 75.7% of the variation at the 3- leaf, jointing, grain filling and maturity stages, respectively (Fig. 8). The

![]()

![]()

Linear mixed-effects model (LME) for treatments (Treatment; CK, T1 and T2), growing stages (Stage), and their interactive effects on leaf rolling index, leaf erection index and spatial density of leaf area.

![]()

Spatial density of leaf area

Intercept 1 69 45,600.08 < 0.0001

Treatment 2 69 47.17 < 0.0001

Treatment 2 69 47.17 < 0.0001

Stages 4 69 28.37 < 0.0001

Treatment×Stage 8 69 5.25 < 0.0001

Intercept 1 69 6633.76 < 0.0001

Treatment 2 69 1.16 0.0194

Stages 4 69 249.01 < 0.0001

![]() Treatment×Stage 8 69 0.22 0.0855

Treatment×Stage 8 69 0.22 0.0855

Note: numDF, numerator degrees of freedom; denDF, denominator degrees of freedom. CK, no straw (traditional tillage); T1, straw mulch (traditional straw returning); T2, ammoniated straw incorporated into the soil (optimized straw returning). A LME was used to test for differences, i.e., to evaluate effects on leaf rolling index, leaf erection index and spatial density of leaf area, we set treatments (Treatment), growing stages (Stage) and their interactions (Treatment×Stage) as fixed effects, and plot as a random factor.

WUE, grain yield and HI were positively correlated with principal component one (Axis 1), while the GCC was closely positively correlated with principal component two (Axis 2). There were negative correla- tions of Axis 2 with SWS at grain filling and maturity stages (Fig. 8c and d). In addition, the LRI and SWS were put on in quadrant III at grain filling and maturity stages. A correlation analysis was performed be- tween HW, GY, BIO, LEI, LRI, GCC, PW, SDA, WUE, HI, and ET (Fig. 9).

The GY had significant positive correlations with BIO (0.94), WUE (0.92) and HI (0.79). And, the GY and BIO had the highest correlation

coefficient (0.94). The LEI had negative correlations with LRI (–0.65) and SDA (–0.69). The WUE had significant positive correlations with

HW, GY, and BIO; WUE and GY had the highest correlation coefficient (0.92).

4.1. Soil water

Our results demonstrated that the straw returning treatments (T1 and T2) increased the 0–100 cm soil water during the early growing stages (3-leaf and jointing stages) of summer maize (Figs. 3 and 4). The significant soil water advantages for straw application compared to

Fig. 6. Boxplots show spatial density of leaf area in the 2016–2018 summer maize growing seasons. Note: CK, no straw (traditional tillage); T1, straw mulch (traditional straw returning); T2, ammoniated straw incorporated into the soil (optimized straw returning). Different lowercase letters denote significant differences between treatments (n = 3).

![]()

![]()

Fig. 7. Relationships between plant water content and changes in (a) aboveground biomass and (b) green canopy cover in the 2016–2018 summer maize growing seasons. Relationships occurred for plant water content and changes in aboveground biomass (Y = — 1204.7X + 1106.9, R2 = 0.64, df = 23, F = 70.37,

p < 0.0001) and changes in green canopy cover (Y = 1.8766X + 2.2387, R2 = 0.79, df = 23, F = 9.73, p = 0.0048). The solid black lines indicate significant slopes for the linear mixed-effects model, and gray shaded areas present the 95% CI for slopes.

The 100-kernel weight, grain yield, aboveground biomass, harvest index, evapotranspiration (ET) and water use efficiency (WUE) at harvest in the 2016–2018 summer maize growing seasons.

![]()

2017

2018

T1 34.1 ± 6.9ab 7178 ± 239b 13,027 ± 339b 55.1 ± 0.71b 363.4 ± 8.2a 19.8 ± 2.9ab

![]() T2 34.4 ± 7.5a 7460 ± 221a 13,121 ± 487a 56.8 ± 0.45a 343 ± 10.1b 21.7 ± 2.2a

T2 34.4 ± 7.5a 7460 ± 221a 13,121 ± 487a 56.8 ± 0.45a 343 ± 10.1b 21.7 ± 2.2a

CK 33.8 ± 8.1c 9790 ± 197c 16,084 ± 399c 60.9 ± 0.49b 379.1 ± 12.5a 25.8 ± 1.6b

T1 35.1 ± 6.4b 10,201 ± 251b 16,114 ± 521b 63.3 ± 0.48a 373.4 ± 5.9a 27.3 ± 4.3a

T2 36.4 ± 7.7a 10,316 ± 352a 16,231 ± 411a 63.6 ± 0.86a 371 ± 8.7a 27.8 ± 4.0a

CK 33.8 ± 6.1c 9081 ± 253c 16,541 ± 356c 54.9 ± 0.71c 384.1 ± 9.5a 23.6 ± 2.7c

T1 35.7 ± 4.7b 9453 ± 187b 16,556 ± 367ab 57.1 ± 0.51b 379.4 ± 8.6a 24.9 ± 2.2b

T2 37.6 ± 5.2a 10,299 ± 219a 17,487 ± 419a 58.9 ± 0.52a 376 ± 11.1a 27.4 ± 1.9a

![]()

Note: CK, no straw (traditional tillage); T1, straw mulch (traditional straw returning); T2, ammoniated straw incorporated into the soil (optimized straw returning). Values are mean ± SE (n = 3). The same letters within a column in each growing season do not significantly differ according to Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05).

traditional tillage (e.g., only chemical fertilization) were also every- where reported from other planting systems (Chen et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2021). In this study, one of the major purposes of the optimized straw incorporation (T2 treatment) was to increase the soil water and improve summer maize growth. Recent findings from our experiment site confirmed that the T2 treatment enhanced annual soil water storage, which may explain the higher maize production of the T2 treatment compared to the CK treatment (Zou et al., 2020). Soil water plays a very crucial role in promoting crop yield production (Shaver et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2014). The increase in soil water content under straw addition was likely due to the increased amounts of precipitation during the growing seasons (Bu et al., 2013; Ding et al. 2018; Li et al., 2020). In addition, the excessive irrigation and chemical fertilizer may lead to low water use efficiency and the contamination of water resources (Hassanli et al., 2009; Yan et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2021). Although irrigation has been used to increase crop production in arid areas of China (Yan et al., 2017), available water resources are severe shortage in agricultural croplands (Panda et al., 2004; Tolk et al., 1999). Therefore, for summer maize cultivation under rainfed drylands, exploring optimal straw returning may be one of the most promising options to improve the use of available water resources and increase summer maize production.

In our study, the T2 treatment had lower ET than the CK and T1 treatments (Tables 2 and 3). Straw returning could reduce soil evapo- ration, which favors soil water storage in semiarid croplands (Zhao et al., 2014). Studies have linked increasing soil water content to

increasing precipitation (i.e., mainly in September) and decreasing evaporation during crop growth (Zhang et al., 2010). Li et al. (2013) reported that straw addition impeded evaporation losses during maize growth period, which is consistent with the findings in our study. In addition, the seasonal WUE results in the current study were consistent with those of Hsiao and Acevedo (1974), i.e., straw mulching reduced soil surface evaporation. We found that straw with a low C/N ratio increased soil water storage compared to traditional straw returning (Fig. 4). The ammoniated straw incorporation (T2) increased WUE and decreased ET during three maize growing seasons (Table 3), which is in line with Yu et al. (2017). The T2 treatment may reduce evaporation and improve soil moisture for maize growth (Table 3). Straw application could decrease early evaporation and change water consumption pat- terns from soil water evaporation to crop transpiration (Deng et al., 2006; Li et al., 2013). Different mulching technologies have varying effects on water consumption (Fan et al., 2016; Li et al., 2013). Here, straw with a low C/N ratio (T2) increased WUE compared to the CK and T1 treatments, in a semi-arid growing season, improving the soil water regime to increase summer maize growth.

4.2. Summer maize growth

Across the three growing seasons, our results indicated that the T2 treatment improved summer maize growth (i.e., higher average of LAI, leaf erection index, spatial density of leaf area, plant height and green

![]()

![]()

Linear mixed-effects model (LME) for treatments (Treatment; CK, T1 and T2), growing year (Year), and their interactive effects on grain yield, aboveground biomass, and water use efficiency (WUE).

Linear mixed-effects model (LME) for treatments (Treatment; CK, T1 and T2), growing year (Year), and their interactive effects on grain yield, aboveground biomass, and water use efficiency (WUE).

WUE

Note: numDF, numerator degrees of freedom; denDF, denominator degrees of freedom. CK, no straw (traditional tillage); T1, straw mulch (traditional straw returning); T2, ammoniated straw incorporated into the soil (optimized straw returning). A LME was used to test for differences, i.e., to evaluate effects on grain yield, we set treatments (Treatment), growing years (Year) and their interactions (Treatment×Year) as fixed effects, and plots as random factor; and to evaluate effects on aboveground and WUE, we set treatments (Treatment) as fixed effects, and plot as a random factor.

![]()

canopy cover) in comparison to the CK and T1 treatments (Figs. 5, 6, S1, S2 and S3). Previous studies have demonstrated that straw application could conserve soil water and impede weed growth (Rahman et al., 2005). Gao et al. (2009) and Hsiao and Acevedo (1974) stated that straw addition could decrease leaf growth at emergence stage. However, the effect of straw application on crop growth and grain yield has been inconsistent. Chen et al. (2015) stated that straw returning increased winter wheat yields compared with no straw returning. Tu et al. (2006) reported straw addition could improve maize growth by increasing leaf area and plant height at jointing and silking stages. This complies very well with recent results from our experimental site, which confirmed that the T2 treatment increased leaf area and plant height, explaining the higher aboveground biomass of the T2 treatment relative to the CK and T1 treatments (Figs. S1 and S2). One explanation might be that the increased leaf growth under the T2 treatment due to soil nutrient dy- namics caused by straw decomposition (Guan et al., 2020). Soil water stress may be one of the most important factors decreasing LAI and plant height (Bai et al., 2009). Zheng et al. (2018) stated that the maximum LAI occurred at the grain filling stage before decreasing gradually due to leaf senescence. Leaf rolling index, spatial density of leaf area and leaf erection index as the key parameters of plant growth characteristics, can be a sensitive indicator for soil water at different growing stages (Song et al., 2018; Xiang et al., 2012). Collectively, based on the present study, the ammoniated straw incorporated into the croplands is essential to summer maize growth, offering the potential to improve aboveground biomass and grain yield in semi-arid croplands.

In our study, the T2 treatment had the highest average total dry biomass and grain yield across the three growing seasons, suggesting that ammoniated crop straw improved grain yield (Table 3). Indeed, the T1 and T2 treatments had higher aboveground biomass and grain yield than the CK treatment, supporting the suggestion that straw with low C/ N ratios increased grain productivity (Ishfaq et al., 2020; Plante et al., 2006). Zou et al. (2020) also reported that ammoniated straw could increase grain yield of winter wheat. The increase in aboveground biomass would be attributed to leaf and plant growth (Bavec and Bavec, 2002; Borr´as et al., 2007). Li et al. (2013) stated that the increase in aboveground biomass and yield induced by straw addition was associ- ated with an improvement in leaf area index and leaf growth. The response of aboveground biomass varied with the T1 and T2 treatments (Fig. 6), and was consistent with the reported link between leaf growth and plant growth (Campos et al., 2004). Further research is urgently

needed to explain the influences of ammoniated straw management on leaf photosynthetic characteristics and associations with biomass, grain yield, and nitrogen-use efficiency in semi-arid zones.

Across the three consecutive growing seasons of summer maize, the negative correlation was found between leaf rolling index and leaf erection index (Fig. 9). Plant height has been closely correlated with total leaf area (Liu et al., 2017), suggesting that maize canopy structure could help researchers evaluate morphological traits and spatial density of leaf area in maize (Ma et al., 2014). Straw incorporation favored maize growth (Tables 3 and 4; Figs. 8 and 9), which may be due to the changes in soil moisture responses to straw incorporated into the soil. Significant positive associations occurred among aboveground biomass, yield and WUE (p < 0.05; Fig. 9). Leaf growth may be correlated with canopy growth, which might be correlated with crop biomass (Ciganda et al., 2009; Ma et al., 2014; Uddling et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2019). To clarify the impacts of the T2 treatment on soil water, maize growth and grain yield, long-term continuous observations and field samplings are urgently warranted.

Across the 3-year study, we found that the T2 treatment increased soil water storage, enhanced grain yield, and promoted WUE, relative to the CK and T1 treatments. Also, the T2 treatment improved maize growth, i.e., the T2 treatment had a higher leaf erection index, spatial density of leaf area, green canopy cover, and aboveground biomass during maize growing seasons. The T2 treatment can maintain or in- crease grain yield and aboveground biomass during three growing years. Furthermore, those findings are beneficial for better understanding the maize planting system that increases soil water storage and crop pro- duction by applying optimized straw practices. Long-term and contin- uous field observations or measurements in the same agroecosystems are urgently warranted to clarify the effects of ammoniated straw incorpo- ration on long-term crop growth and soil water changes in semiarid regions.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

![]()

![]()

Fig. 8. Principal component analysis (PCA) of soil water parameters [SWS (soil water storage), θ (plant water content), ET (evaporation) and WUE (water use efficiency)] and summer maize growth indices [LAI (leaf area index), LEI (leaf erection index), LRI (leaf rolling index), GCC (green canopy cover), height (plant height), dry bio. (dry aboveground biomass), Yield (maize yield), HI (harvest index), kernel weight (100-kernel weight), and fresh bio. (fresh aboveground biomass)]

under three treatments at the (a) 3-leaf stage, (b) jointing stage, (c) grain filling stage, and (d) maturity stages.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Fig. 9. Scatter matrix plots between hundred-grain weight (HW), grain yield (GY), aboveground biomass (BIO), leaf rolling index (LEI), leaf erection index (LRI), green canopy cover (GCC), plant water (PW), spatial density of leaf areas (SDA), water use efficiency (WUE), harvest index (HI), and evapotranspiration (ET) for the 2016–018 summer maize growing seasons. Lower panels indicate scatterplots with red lines presenting the best fit, upper panels show Pearson’s correlation co-

efficients, and diagonal panel shows phenotypic traits with histograms. *, ** and *** indicate significance levels of p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

![]()

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51609237 and 51879224), 111 Project of the Ministry of Education and the State Administration of Foreign Experts Affairs (B12007), and Key R&D projects of Shaanxi Province (2019NY-190). This work was also financially supported by the China Scholarship Council (No. 202006300072) and supported by Aarhus University. Thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable review and com- ments on the manuscript.

Appendix A. Supporting information

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2021.106948.

Angers, D.A., Recous, S., 1997. Decomposition of wheat straw and rye residues as affected by particle size. Plant Soil 189 (2), 197–203.

Bai, X.L., Sun, S., Yang, G., Liu, M., Zhang, Z., Qi, H., 2009. Effect of water stress on

maize yield during different growing stages. J. Maize Sci. 17 (2), 60–63.

Battaglia, M., Thomason, W., Fike, J.H., Evanylo, G.K., von Cossel, M., Babur, E., Iqbal, Y., Diatta, A.A., 2021. The broad impacts of corn stover and wheat straw removal for biofuel production on crop productivity, soil health and greenhouse gas

emissions: a review. Glob. Chang. Biol. Bioenergy 13, 45–57.

Bavec, F., Bavec, M., 2002. Effects of plant population on leaf area index, cob characteristics and grain yield of early maturing maize cultivars (FAO 100–400). Eur. J. Agron. 16, 151–159.

Bhella, H.S., 1988. Effect of trickle irrigation and black mulch on growth, yield, and

mineral composition of watermelon. Hort Science 23 (1), 123–125.

Borr´as, L., Westgate, M.E., Astini, J.P., Echarte, L., 2007. Coupling time to silking with plant growth rate in maize. Field Crop. Res. 102 (1), 73–85.

Bu, L.D., Liu, J.L., Zhu, L., Luo, S.S., Chen, X.P., Li, S.Q., Hill, R.L., Zhao, Y., 2013. The

effects of mulching on maize growth, yield and water use in a semi-arid region. Agric. Water Manag. 123, 71–78.

Cabiles, D., Angeles, O.R., Johnson-Beebout, S.E., Sanchez, P.B., Buresh, R.J., 2008.

Faster residue decomposition of brittle stem rice mutant due to finer breakage during threshing. Soil Tillage Res. 98 (2), 211–216.

Campos, H., Cooper, M., Habben, J.E., Edmeades, G.O., Schussler, J.R., 2004. Improving

drought tolerance in maize: a view from industry. Field Crop. Res. 90 (1), 19–34.

Chen, S., Zhang, X., Pei, D., Sun, H., Chen, S., 2007. Effects of straw mulching on soil temperature, evaporation and yield of winter wheat: field experiments on the North

China Plain. Ann. Appl. Biol. 150, 261–268.

Chen, Y.L., Liu, T., Tian, X.H., Wang, X.F., Li, M., Wang, S.X., Wang, Z., 2015. Effects of

plastic film combined with straw mulch on grain yield and water use efficiency of winter wheat in Loess Plateau. Field Crop. Res. 172, 53–58.

Ciganda, V., Gitelson, A., Schepers, J., 2009. Non-destructive determination of maize leaf and canopy chlorophyll content. J. Plant Physiol. 166, 157–167.

Deng, X.P., Shan, L., Zhang, H., Turner, N.C., 2006. Improving agricultural water use

efficiency in arid and semiarid areas of China. Agric. Water Manag. 80, 23–40.

Ding, D., Zhao, Y., Feng, H., Hill, R.L., Chu, X., Zhang, T., He, J., 2018. Soil water

utilization with plastic mulching for a winter wheat-summer maize rotation system on the Loess Plateau of China. Agric. Water Manag. 201, 246–257.

Dong, Q.G., Li, Y., Feng, H., Yu, K., Dong, W.J., Ding, D.Y., 2018. Effects of ammoniated

straw incorporation on soil water and yield of summer maize (Zea mays L.). Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 49 (11), 220–229.

Fan, Y., Ding, R., Kang, S., Hao, X., Du, T., Tong, L., Li, S., 2016. Plastic mulch decreases available energy and evapotranspiration and improves yield and water use efficiency

in an irrigated maize cropland. Agric. Water Manag. 179, 122–131.

Franzluebbers, A.J., 2002. Water infiltration and soil structure related to organic matter and its stratification with depth. Soil Tillage Res. 66 (2), 197–205.

Gao, Y., Li, Y., Zhang, J., Liu, W., Dang, Z., Cao, W., Qiang, Q., 2009. Effects of mulch, N fertilizer, and plant density on wheat yield, wheat nitrogen uptake, and residual soil

nitrate in a dryland area of China. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 85 (2), 109–121.

Guan, X.K., Wei, L., Neil, C.T., Ma, S.C., Yang, M.D., Wang, T.C., 2020. Improved straw management practices promote in situ straw decomposition and nutrient release, and increase crop production. J. Clean. Prod. 250, 119514.

Hassanli, A., Ebrahimizadeh, M.A., Beecham, S., 2009. The effects of irrigation methods with effluent and irrigation scheduling on water use efficiency and corn yields in an arid region. Agric. Water Manag. 96 (1), 93–99.

![]()

![]()

Hsiao, T.C., Acevedo, E., 1974. Plant responses to water deficits, water-use efficiency, and drought resistance. Agric. Meteorol. 14 (1), 59–84.

Hsiao, T.C., Heng, L., Stedutob, P., Rojas-Laraa, B., Raesc, D., Fereresd, E., 2009.

AquaCrop—The FAO crop model to simulate yield response to water: III. Parameterization and testing for maize. Agron. J. 101 (3), 448–459.

IPCC, 2013. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Ishfaq, A., Burhan, A., Kenneth, B., 2020. Adaptation strategies for maize production under climate change for semi-arid environments. Eur. J. Agron. 115, 126040.

Ka¨nka¨nen, H., Alakukku, L., Salo, Y., Pitka¨nena, T., 2011. Growth and yield of spring

cereals during transition to zero tillage on clay soils. Eur. J. Agron. 34 (1), 35–45. Li, S.X., Wang, Z.H., Li, S.Q., Gao, Y.J., Tian, X.H., 2013. Effect of plastic sheet mulch, wheat straw mulch, and maize growth on water loss by evaporation in dryland areas

of China. Agric. Water Manag. 116, 39–49.

Li, Y., Chen, H., Feng, H., Dong, Q.G., Wu, W.J., Zou, Y.F., Henry, Chau, Siddique, K.H. M., 2020. Influence of straw incorporation on soil water utilization and summer maize productivity: a five-year field study on the Loess Plateau of China. Agric.

Liu, C., Lu, M., Cui, J., Li, B., Fang, C., 2014. Effects of straw carbon input on carbon dynamics in agricultural soils: a meta-analysis. Glob. Chang. Biol. 20, 1366–1381.

Liu, G.Z., Hou, P., Xie, R.A., Ming, B., Wang, K.R., Xu, W.J., Liu, W.M., Yang, Y.S., Li, S.

K., 2017. Canopy characteristics of high-yield maize with yield potential of 22.5 Mg ha—1. Field Crop. Res. 213, 221–230.

Ma, D.L., Xie, R.Z., Niu, X.K., Li, S.K., Long, H.L., Liu, Y.E., 2014. Changes in the

morphological traits of maize genotypes in China between the 1950 and 2000. Eur. J. Agron. 58, 1–10.

Mann, M.E., Cohen, R.D.H., Kernan, J.A., Nicholson, H.H., Christensen, D.A., Smart, M. E., 1988. The feeding value of ammoniated flax straw, wheat straw and wheat chaff

for beef cattle. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 21 (1), 57–66.

Mckee, G.W., 1964. A coefficient for computing leaf area in hybrid corn. Agron. J. 56 (2), 240–241.

Panda, R.K., Behera, S.K., Kashyap, P.S., 2004. Effective management of irrigation water for wheat under stressed conditions. Agric. Water Manag. 66 (3), 181–203.

Parfitt, R.I., Stott, K.G., 1984. Effects of mulch covers and herbicides on the

establishment, growth, and nutrition of poplar and willow cuttings. Asp. Appl. Biol. 5, 305–313.

Plante, A.F., Stewart, C.E., Conant, R.T., Paustian, K., Six, J., 2006. Soil management effects on organic carbon in isolated fractions of a Gray Luvisol. Can. J. Soil Sci. 86

R Core Team, 2013. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. URL. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

Rahman, M.A., Chikushi, J., Saifizzaman, M., Lauren, J.G., 2005. Rice straw mulching and nitrogen response of no-till wheat following rice in Bangladesh. Field Crop. Res.

Ram, H., Dadhwal, V., Vashist, K.K., Kaur, H., 2013. Grain yield and water use efficiency

of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) in relation to irrigation levels and rice straw mulching in North West India. Agric. Water Manag. 128, 92–101.

Romic, D., Romic, M., Borosic, J., Poljak, M., 2003. Mulching decreases nitrate leaching in bell pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) cultivation. Agric. Water Manag. 60 (2), 87–97.

Shaver, T.M., Peterson, G.A., Ahuja, L.R., Westfall, D.G., 2013. Soil sorptivity

enhancement with crop residue accumulation in semiarid; dryland no-till agroecosystems. Geoderma 192 (1), 254–258.

Singh, G., Laryea, K.B., Karwasra, S.P.S., Pathak, P., 1993. Tillage methods related to soil and water conservation in South Asia. Soil Tillage Res. 27 (1–4), 273–282.

Song, H., Li, Y., Zhou, L., Xu, Z., Zhou, G., 2018. Maize leaf functional responses to

drought episode and rewatering. Agric. For. Meteorol. 249, 57–70.

Sun, C., Gao, X., Chen, X., Fu, J., Zhang, Y., 2016. Metabolic and growth responses of

maize to successive drought and re-watering cycles. Agric. Water Manag. 172, 62–73.

Tolk, A., Howell, T.A., Evett, S.R., 1999. Effect of mulch, irrigation, and soil type on

water use and yield of maize. Soil Tillage Res. 50 (2), 137–147.

Tu, C., Ristaino, J.B., Hu, S., 2006. Soil microbial biomass and activity in organic tomato

farming systems: effects of organic inputs and straw mulching. Soil Biol. Biochem. 38 (2), 247–255.

Uddling, J., Gelang-Alfredsson, J., Piikki, K., Pleijel, H., 2007. Evaluating the relationship between leaf chlorophyll concentration and SPAD-502 chlorophyll

meter readings. Photosynth. Res. 91, 37–46.

Wang, H., Shen, M., Hui, D., Chen, J., Sun, G., Wang, X., Zhang, Y., 2019. Straw incorporation influences soil organic carbon sequestration, greenhouse gas emission,

and crop yields in a Chinese rice (Oryza sativa L.) –wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)

cropping system. Soil Tillage Res. 195, 104377.

Xia, L., Lam, S.K., Wolf, B., Kiese, R., Chen, D., Butterbach-Bahl, K., 2018. Trade-offs

between soil carbon sequestration and reactive nitrogen losses under straw return in global agroecosystems. Glob. Chang. Biol. 24, 5919–5932.

Xiang, J.J., Zhang, G.H., Qian, Q., Xue, H.W., 2012. Semi-rolled leaf encodes a putative glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein and modulates rice leaf rolling by

regulating the formation of bulliform cells. Plant Physiol. 159 (4), 1488–1500.

Yan, Z., Gao, C., Ren, Y., Zong, R., Ma, Y., Li, Q., 2017. Effects of pre-sowing irrigation and straw mulching on the grain yield and water use efficiency of summer maize in

the north china plain. Agric. Water Manag. 186, 21–28.

Yu, K., Dong, Q.G., Chen, H.X., Feng, H., Zhao, Y., Si, B.C., Li, Y., Hopkins, D.W., 2017.

Incorporation of pre-treated straw improves soil aggregate stability and increases crop productivity. Agron. J. 109, 2253–2265.

Zhang, X., Chen, S., Sun, H., Wang, Y., Shao, L., 2010. Water use efficiency and

associated traits in winter wheat cultivars in the North China Plain. Agric. Water Manag. 97 (8), 1117–1125.

Zhang, Y., Wang, J., Gong, S., Xu, D., Mo, Y., Zhang, B., 2021. Straw mulching improves soil water content, increases flag leaf photosynthetic parameters and maintaines the yield of winter wheat with different irrigation amounts. Agric. Water Manag. 249, 106809.

Zhao, Y., Pang, H., Wang, J., Huo, L., Li, Y., 2014. Effects of straw mulch and buried

straw on soil moisture and salinity in relation to sunflower growth and yield. Field Crop. Res. 161, 16–25.

Zheng, J., Fan, J., Zhang, F., Yan, S., Xiang, Y., 2018. Rainfall partitioning into throughfall, stem flow and interception loss by maize canopy on the semi-arid Loess

Plateau of China. Agric. Water Manag. 195, 25–36.

Zou, Y., Feng, H., Wu, S., Dong, Q.G., Siddique, K.H.M., 2020. An ammoniated straw incorporation increased biomass production and water use efficiency in an annual wheat–maize rotation system in semi-arid China. Agronomy 10 (2), 243.

![]()