通过增加渗透和减少蒸发,覆盖可以改善半干旱地区的土壤水环境和果园的苹果产量

![]()

Agricultural Water Management 253 (2021) 106936

Agricultural Water Management 253 (2021) 106936

![]()

By increasing infiltration and reducing evaporation, mulching can improve ![]() the soil water environment and apple yield of orchards in semiarid areas

the soil water environment and apple yield of orchards in semiarid areas

Yang Liao, Hong-Xia Cao *, Xing Liu, Huang-Tao Li, Qing-Yang Hu, Wen-Kai Xue

Key Laboratory of Agricultural Soil and Water Engineering in Arid and Semiarid Areas, Ministry of Education, Northwest A&F University, Yangling 712100, China

![]()

A R T I C L E I N F O

![]() Handling Editor - Dr. B.E. Clothier

Handling Editor - Dr. B.E. Clothier

![]() Keywords: Mulching Infiltration Evaporation Soil water Orchards Yield

Keywords: Mulching Infiltration Evaporation Soil water Orchards Yield

A B S T R A C T

![]()

Infiltration and evaporation are two important components of soil water balance in semiarid areas. For local orchards using drip irrigation, rainfall and irrigation events have a profound impact on soil infiltration and evaporation. As an effective water conservation technique, soil surface mulching is widely used in semiarid areas. The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of mulching (e.g., horticultural fabric mulching and corn straw mulching) on soil infiltration and evaporation after irrigation and rainfall. Through field experiments, we investigated soil infiltration and evaporation during three wet-dry cycles and for a rainy month and studied the effects of mulching on soil physical properties and apple yields. The results showed that both horticultural fabric mulching (FM) and straw mulching (SM) improved soil physical properties by reducing soil bulk density and increasing porosity and that SM had a better effect. Mulching increased infiltration after irrigation and heavy rain, while SM reduced infiltration when light rain occurred. Regardless of whether the soil was in the energy- limited stage or falling-rate stage, mulching can effectively reduce soil evaporation. We determined that the threshold of soil water content (SWC) between the energy-limited stage and falling-rate stage was 22.09–22.75%. When SWC is lower than the threshold, there is a positive significant correlation between evaporation and SWC, while no significant correlation was found when it is above the threshold. Moreover, mulching effectively increased apple yields and irrigation water use efficiency (IWUE) for three consecutive years. Therefore, both FM and SM have potential for application in orchards in semiarid areas to improve soil and moisture conditions in the root zone.

![]()

Apple trees are one of the most important perennial fruit trees planted in the Loess Plateau of China. However, due to drought and serious soil erosion, sustainable development of the apple industry in this region has been seriously affected (Zhong et al., 2019). In recent years, the apple industry in Shaanxi Province has expanded rapidly from semi-humid areas to semi-arid areas, which further aggravates the contradiction between supply and demand of water resources (Yang et al., 2020). Therefore, maintaining sufficient soil moisture storage is very important for this industry. In local apple orchards, rainfall is the main source of soil water supplements. However, due to the character- istics of scarce and uneven rainfall, drip irrigation was introduced to supplement soil moisture. Evaporation and infiltration are two types of soil water movement for maintaining soil water balance. In the context of climate change, increasing infiltration from precipitation and irriga- tion and decreasing soil evaporation are therefore of great importance to

the sustainability of agriculture in water-limited regions (Li et al., 2018; Cao et al.,2009).

Water infiltration is an important process of mutual transformation of rainwater, irrigation water, surface water, soil water and ground- water. Water infiltration is affected by irrigation amounts, precipitation characteristics, canopy interception capacities and soil hydraulic char- acteristics (Khan et al., 2016). In general, when rainfall occurs, due to the low initial soil water content (SWC), a large amount of rainwater infiltrates into the soil and is converted into soil water. If the rainfall amount is large, as infiltration progresses, soil water gradually becomes saturated, and the infiltration rate gradually becomes lower than the rainfall intensity, rainwater gathers on the soil surface to form surface water and runoff and is ultimately lost. Furthermore, surface runoff causes severe soil degradation and loss of sustainable production through soil erosion and nutrient loss (Liu et al., 2012, 2018; Prosdocimi et al., 2016).

Under the influence of atmospheric radiant heat, soil water

![]()

* Correspondence to: No. 26, Weihui Road, Yangling, Shaanxi 712100, China.

E-mail addresses: ly0225@126.com (Y. Liao), nschx225@nwafu.edu.cn (H.-X. Cao).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2021.106936

Received 9 December 2020; Received in revised form 18 April 2021; Accepted 19 April 2021

Available online 29 April 2021

0378-3774/© 2021 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

![]()

![]()

evaporates at the soil-atmosphere interface. However, this portion of soil water loss is often regarded as invalid water consumption because it does not participate in biomass formation or yields (Chen et al., 2015; Ram et al., 2013). Some scholars have found that when evaporation decreases due to the controlling effect of mulching, plant transpiration increases in some field crops (Singh et al., 2011; Li et al., 2008). In field environments, soil water evaporation can be divided into two stages. When rainfall or irrigation have just ended, SWC is high, and soil evaporation has nothing to do with SWC and is only determined by meteorological factors (e.g., air temperature, solar radiation, wind speed and air humidity), this stage is called “energy-limited stage”. During this energy-limited stage, the soil evaporation rate is relatively constant and occurs at a maximum rate that is limited only by meteorological con- ditions (Zribi et al., 2015). When SWC drops to a certain threshold, the “energy-limited stage” ends. Due to the low SWC, the ability of soil to transport water upward is weakened, which makes it difficult to meet the demand of atmospheric evaporation in the surface layer. The evaporation rate depends on the demand for atmospheric evaporation and the ability of soil to transport water upward. During this stage, the evaporation rate is reduced in proportion to the water available at the soil surface, and this stage is called “falling-rate stage”(Allen et al., 1998).

As an effective water conservation technique, soil surface mulching is widely used in arid and semiarid areas (Chakraborty et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2009; Zribi et al., 2015). Mulch forms a physical isolation layer on the soil surface, which slows down and hinders exchange of water and energy between the soil and atmosphere. The effectiveness of mulching for soil evaporation control and increasing infiltration has been documented in some studies (Li et al., 2018; Khan et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2009). In addition to the benefits of water conservation, previous studies have shown that soil surface mulching was also reported to regulate soil temperature variations (Olasantan, 1999; Awe et al., 2015; Sarkar et al., 2007), alter soil microbiology (Steinmetz et al., 2016; Carney and Matson, 2005), improve soil physical properties and soil fertility (Smets et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2014; Rodrigues et al., 2013; Jord´an et al., 2010), and affect crop growth, physiology and, ultimately, yields and water use efficiency (Zhang et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015; Abd El-Wahed and Ali, 2013).

In our previous study (Liao et al., 2021), we studied the effect of mulching on SWC during the whole growth period from 2018 to 2019, and found that mulching effectively increased SWC, but the reason was not clear. Infiltration after rainfall and irrigation is the main water replenishment method in this area, while evaporation is the main loss method of field soil water. We hypothesize that given these processes, mulching exerts a great impact on the Soil-Plant-Atmosphere Contin- uum (SPAC) and is different after irrigation and rainfall. This is because water can enter the soil directly during irrigation, while it must pass through the mulching layer first before reaching the soil during rainfall. Regardless of whether rain or irrigation has occurred, mulching can significantly reduce evaporation because it hinders water and vapor exchange between the soil and atmosphere and reduces the amount of heat radiation reaching the ground. However, the effects of mulching on soil infiltration are different after irrigation and rainfall because mulching changes the structure of the underlying surface of the field, and the mulching itself absorbs water, which depends on the mulching material.

Several field experiments were conducted on the control of soil evaporation and regulation of infiltration under mulching, respectively. However, there is a lack of mechanistic research on the effects of mulching on soil evaporation and infiltration after rainfall and irriga- tion, especially for orchards in semiarid areas. During the fruit expan- sion stage (late June to late August), the SWC changed dramatically. In the early fruit expansion stage, the SWC was at the lowest level throughout the growth season due to higher evapotranspiration and less rainfall, while in the late fruit expansion stage, a large amount of rainfall infiltration will lead to the rapid increase of SWC (Liao et al., 2021).

Both soil evaporation and infiltration at this stage are representative. Therefore, we chose the fruit expansion stage to study the effect of Mulching on soil evaporation and infiltration. The specific objectives were to (1) study the infiltration and evaporation processes after rainfall and irrigation and the effects of mulching on them; (2) analyse the relationship between soil evaporation and soil water content; and (3) investigate the effects of mulching on yields and irrigation water use efficiency (IWUE).

2.1. Experiment location

The study was carried out from 2018 to 2020 at a modern agriculture apple demonstration orchard located in Qingshuigou Village, Zizhou County, Yulin City, Shaanxi Province, northwest China (37◦27′ N, 110◦2′ E, altitude: 1020 m). The experimental site is in a typical hilly gully region of the Loess Plateau and has a continental temperate climate with an annual average sunshine duration of over 2543.3 h. The annual average temperature is 9.7 ◦C, and the annual average frost-free period is 170 days. The average annual rainfall is 453 mm, and more than 60% occurs from July to September. The test soil is classified as sandy loam with favourable hydraulic properties (Gao et al., 2018). The mean pH and field capacity (θf) of the one-metre soil layer are 8.5 and 0.30

cm3⋅cm—3, respectively. An automated weather station was installed in

the orchard to monitor meteorological factors such as precipitation, wind velocity, wind direction, solar radiation, atmospheric pressure, air temperature and relative air humidity.

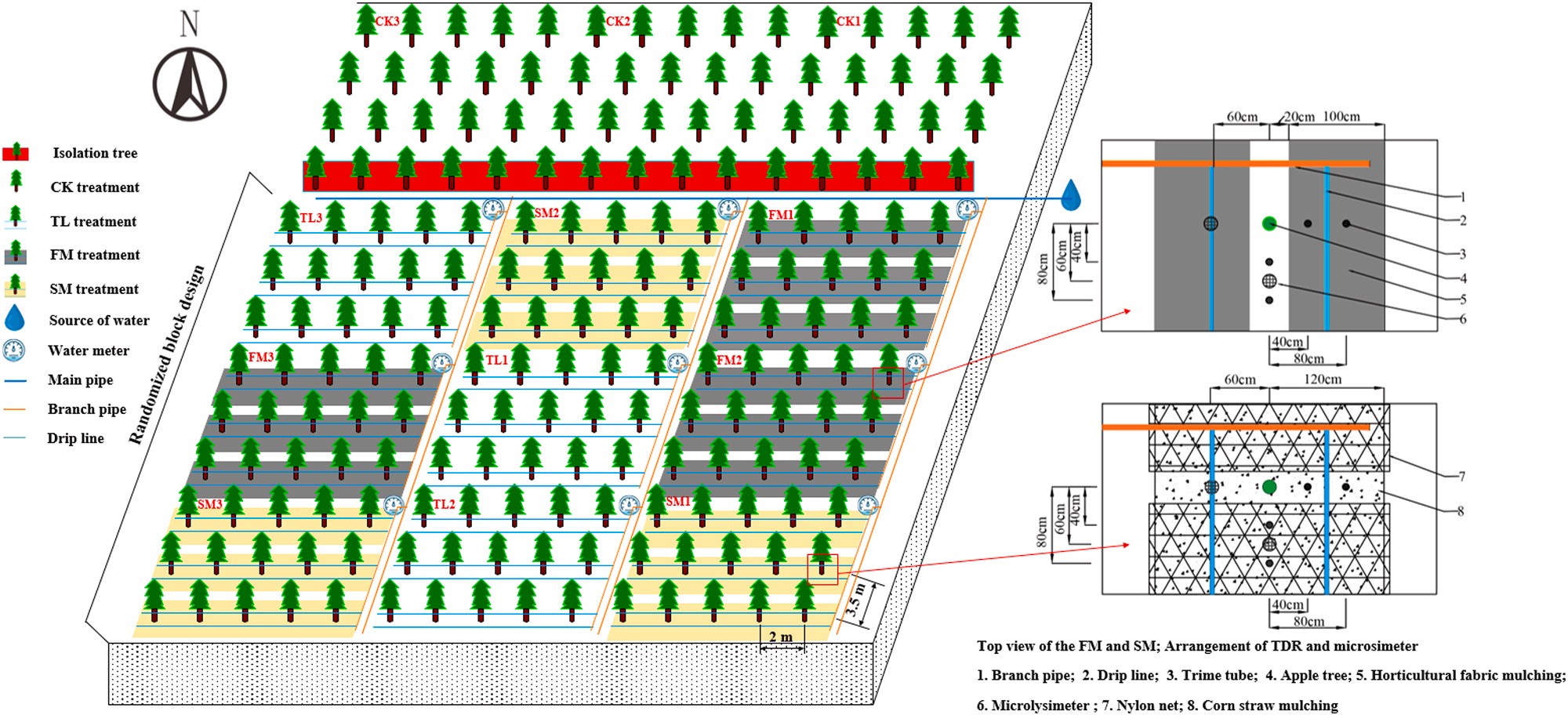

2.2. Experimental design

Eight-year-old ‘Honeycrisp’ apple trees (Malus pumila Mill) with similar trunk diameters and bark depths were selected as the experi- mental trees. The apple trees were planted in an east-west orientation

with a row spacing of 3.5 m and plant spacing of 2 m (1429 plants ha—1).

Each treatment included three rows of apple trees. Three apple trees in each treatment with similar growth vigour and canopy were selected as the experimental trees.

Four treatments were employed: horticultural fabric mulching with drip irrigation (FM), corn straw mulching with drip irrigation (SM), clear tillage with drip irrigation (TL), and clear tillage with rain feeding (CK). The randomized complete block design with a split-plot arrange- ment were adopted in the experiment, each treatment was repeated three times (Fig. 1). More specific details of the mulching treatments are provided in our other report (Liao et al., 2021). In April every year, TL and CK were cultivated to a tillage depth of 30 cm by a mechanical cultivator, while no tillage was implemented for SM and FM. Other agronomic measures were consistent, such as fertilization, weeding, pruning and insecticide spraying.

2.3. Irrigation and soil water monitoring

According to local soil water consumption rates, vertical SWC pro- files were monitored for an approximately 10 days interval with a TRIME-T3 tubular TDR (IMKO Ltd, DE) at 20 cm intervals over the 80 cm-depth soil layer. Two trim tubes for each treatment were installed at horizontal distances of 40 and 80 cm from the tree row (Fig. 1). The SWC for each treatment was the average of the SWCs that were measured by the two trim tubes. Different mulching treatments received the same irrigation amounts, and the irrigation amount applied was defined based on the volumetric SWC of TL. When the SWC of TL was lower than the lower irrigation limit (70% θf), irrigation was carried out. More specific details on irrigation systems and irrigation events are given in Liao et al. (2021).

From June 27 to the end of August 2020, nearly daily continuous monitoring of SWC was carried out to observe SWC variations after rain

![]()

![]()

![]()

and irrigation and to investigate their relationships with evaporation.

Soil water storage (SWS) is a key component of soil water balance and is defined by the formula (1):

Here, θ is the mean volumetric soil water content of a specific soil layer (%), it should be noted that in the rainy August, some measurements of SWC are not carried out on the day of rain or the next day due to the surface water and mud in the field (Table 4); h is the depth of a specific soil layer (mm).

Increased SWS (ΔSWS) after rain or irrigation can be used to assess infiltration efficiency (Song et al., 2020) and was calculated using the following formula (2):

Here, SWS1 is soil water storage after rain or irrigation and SWS0 is soil water storage before rain or irrigation.

2.4. Measurements of soil bulk density and porosity

After the apple harvests in 2019 and 2020, soil bulk density, porosity, capillary porosity and non-capillary porosity were measured at 20 cm intervals over the 60 cm-depth soil layer using the cutting ring method (Bao, 2007). The soil bulk density and porosity in 2018 were not measured because the orchard ground was just covered in April 2018, which may have little impact on the soil.

2.5. Monitoring of evaporation

Soil evaporation was measured by weighing microlysimeters (MLs) at 8:00 every day during fruit expansion (late June to late August) in 2020. Each microlysimeter consisted of an inner cylinder made of PVC pipe and an outer cylinder made of iron sheet. The inner cylinder had a diameter of 10.5 cm and height of 19.5 cm, and the outer cylinder had a slightly larger size to facilitate the tight installation of the inner cylinder into the outer cylinder. A handle was attached to the inner cylinder to facilitate its periodic extraction from the outer cylinder.

Two MLs each treatment were installed on both sides of the tree row, with a horizontal distance of 60 cm from the tree row of each subplot. First, on the day after a rain or irrigation event, the inner cylinder was inserted into the soil to extract the undisturbed soil, and this cylinder

was then was packed with gauze at the bottom. Then, it was weighed by a portable balance (0.01 g precision) and was placed back into the outer cylinder. After that, the inner cylinder was weighed at 8:00 each day to measure the amount of evaporation of the previous day. Long et al. (2010) found that if the soil was not replaced within 15 days, the ac- curacy of soil evaporation was still high. Therefore, the MLs were renewed with undisturbed soil after the next rain (greater than 10 mm) or irrigation or use for more than 15 days. Moreover, for the mulching treatments, the MLs were covered by the mulching layer. In the SM treatment, a 20 cm by 20 cm metal screen was placed on the top of the MLs to prevent straw debris from falling into the MLs. This process was followed during three wet-dry cycles: 27 June (irrigation 15.3 mm) – 7 July, 9 July (one day after rainfall 17.5 mm) – 19 July and 20 July (one day after irrigation 17.2 mm) to 29 July. Due to the high frequency-high magnitude rainfall in August, it was difficult to measure SWC and soil evaporation when rainfall amounts were large. Therefore, in August, there were no long-term continuous observations of soil moisture con- tent and soil evaporation.

In order to eliminate the influence of climate conditions and canopy shading on soil evaporation, we introduced the relative evaporation rate (ER) under the trees, which was calculated using the following formula (3):

Here, E is soil evaporation measured by MLs and Epan is the water surface evaporation measured by two standard 20 cm diameter evaporation pans that were installed on both sides of the tree row at 60 cm horizontal distances from the tree rows. More details on measurements of water surface evaporation are given in Zhao et al. (2020).

2.6. Leaf area index, fruit yield and IWUE

The leaf area index (LAI) was measured by an LI-2200C canopy analysis system (LI-COR, Nebraska, USA). To reduce the influence of strong light, measurements of LAI were performed before sunrise or after sunset.

Apples were harvested and the yield per treatment were weighed on 17 September 2018, 21 September 2019 and 10 September 2020. Irri- gation water use efficiency (IWUE) was calculated using the following formula (Du et al. 2017) (4):

![]()

![]()

![]()

Here, Y is the yield under irrigation (kg ha—1), Y1 is the yield under rainfed conditions, and I is the irrigation amount (mm).

2.7.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed with SPSS 25.0 Sta- tistics (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The least significant difference

![]()

![]()

![]() 40 1.25 40

40 1.25 40

![]() 1.25

1.25

30

0

CK TL

FM SM

1.00

30

0

CK TL

FM SM

1.00

a. 0-20cm (2019)

50

50

1.50 50

d. 0-20cm (2020)

1.50

1.50

![]()

![]() 40 1.25 40

40 1.25 40

![]() 1.25

1.25

30

0

CK TL

FM SM

30

1.00 0

CK TL

FM SM

1.00

b. 20-40cm (2019)

50

50

1.50 50

e. 20-40cm (2020)

1.50

1.50

![]()

![]() 40 1.25 40

40 1.25 40

![]() 1.25

1.25

![]()

![]()

30

0

CK TL

FM SM

1.00

30

0

CK TL

FM SM

1.00

![]()

c. 40-60cm (2019) f. 40-60cm (2020)

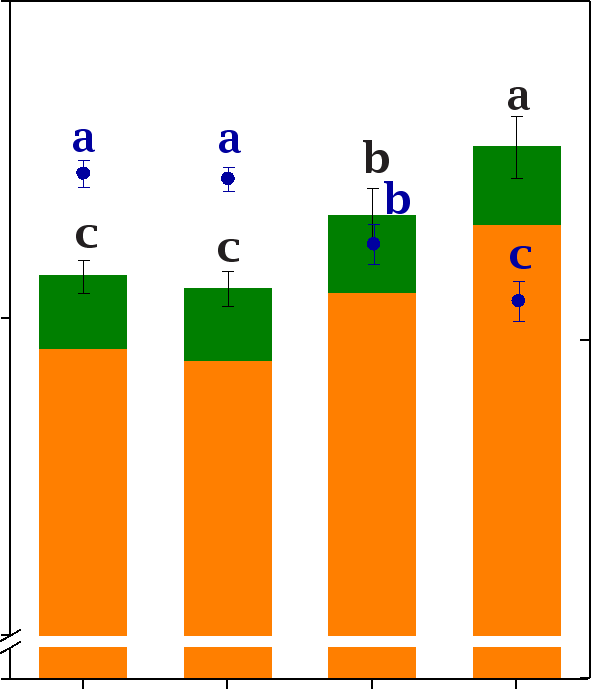

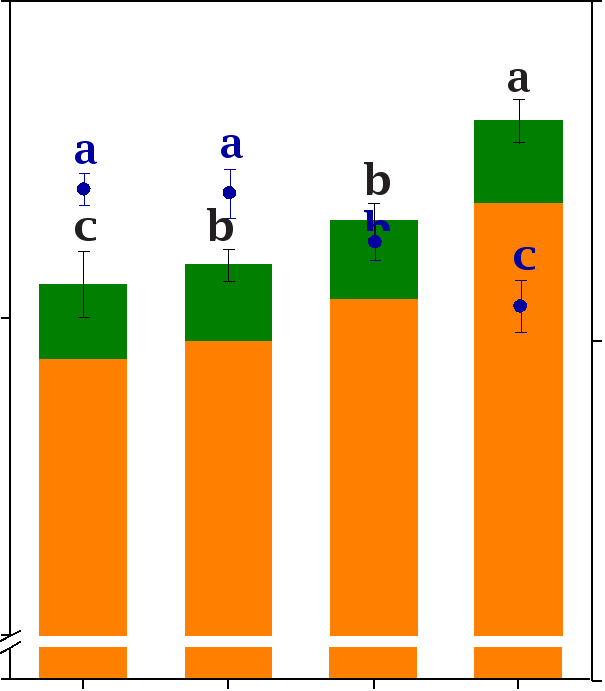

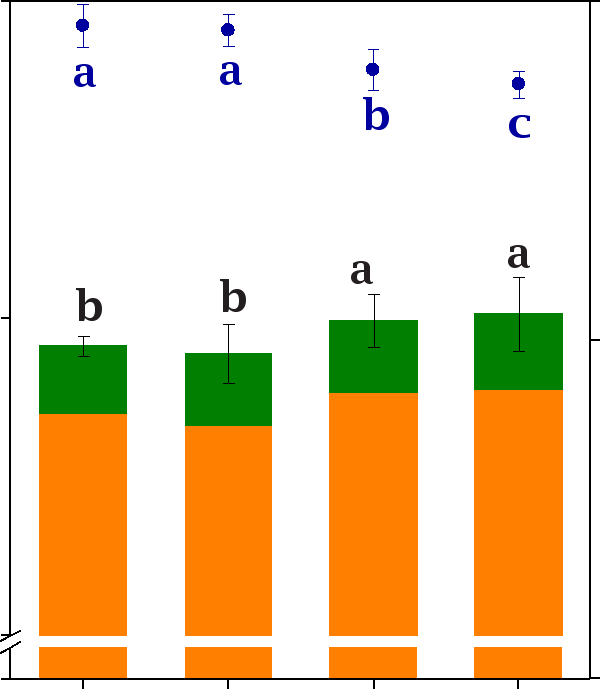

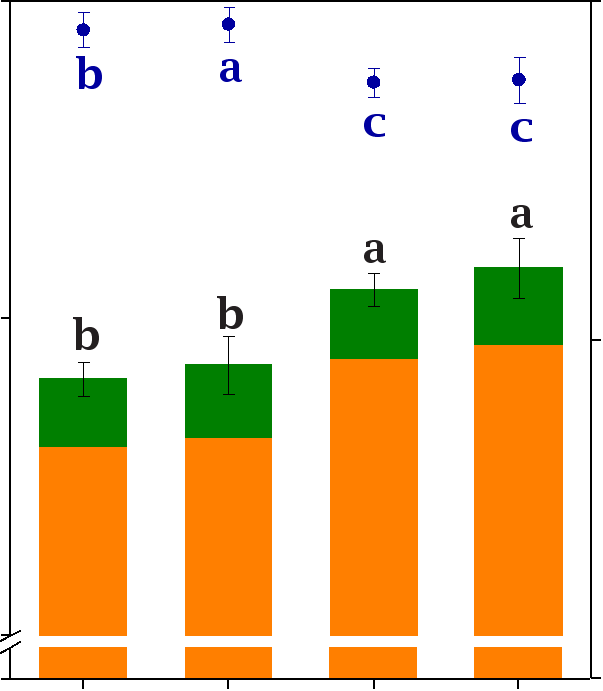

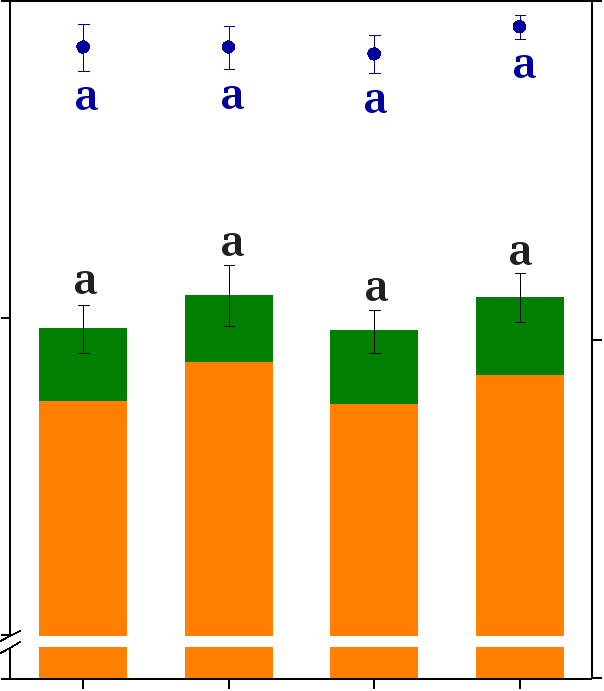

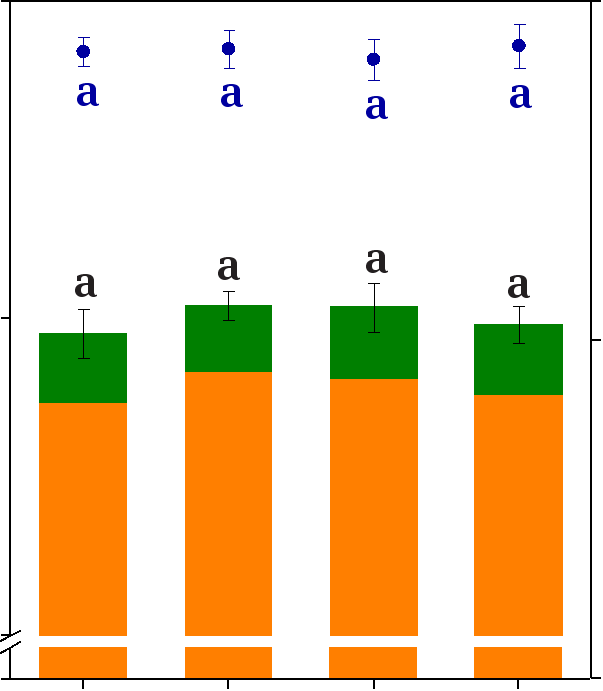

Fig. 2. Soil bulk density and porosity in 0–60 cm soil layer in 2019 and 2020. The error bars represent the standard deviations (black error bars represent the standard deviations of porosity). Different letters within a column indicate significant differences among treatments at P = 0.05 level. TL: clear tillage with drip irrigation; FM: horticultural fabric mulching with drip irrigation; SM: corn straw mulching with drip irrigation; CK: clear tillage with rain feeding.

![]()

![]()

(LSD) at a 5% significance level was used to determine any significant differences. Images were generated using Origin 2018 (OriginLab Inc., Massachusetts, USA).

3.1. Soil bulk density and porosity

In the second (2019) and third (2020) years of the experiment, the soil bulk density of the 0–40 cm soil layer was significantly reduced by mulching, especially in the 0–20 cm soil layer, and there were no sig- nificant differences between the two years (Fig. 2). With increasing soil depth, the soil bulk density first increased and then decreased, with a minimum at 0–20 cm and maximum at 20–40 cm. In the 0–20 cm soil layer, the mean soil bulk densities of FM and SM in the two years were

1.32 g/cm3 and 1.28 g/cm3, which were 3.1% and 6.4% lower than that

of TL (1.36 g/cm3), respectively. In the 20–40 cm soil layer, the mean soil bulk densities of FM and SM in the two years were 1.44 g/cm3 and

1.45 g/cm3, which were 2.7% and 2.5% lower than that of TL (1.48 g/ cm3), respectively. The soil bulk density in the 0–40 cm layer of SM was

significantly lower than that of FM except in the 20–40 cm soil layer in 2020.

In the 0–40 cm soil layer, capillary porosity, non-capillary porosity and total porosity were increased significantly by mulching in the two years (Fig. 2). In contrast to soil bulk density, with increasing soil depth, the porosity first decreased and then increased, with a minimum at 20–40 cm and maximum at 0–20 cm. In the 0–20 cm soil layer, the mean soil porosities of FM and SM in the two years were 43.17% and 45.83%, respectively, which were 4.5% and 10.9% higher than that of TL (41.33%). In the 20–40 cm soil layer, the mean soil porosities of FM and SM of the two years were 39.6% and 40.4%, which were 5.0% and 7.0% higher than that of TL (37.72%), respectively. In the 0–20 cm soil layer, SM soil porosity was significantly higher than FM soil porosity; however, there was no significant difference in the 20–40 cm soil layer.

Regardless of the soil bulk density or porosity, no significant differ- ence was observed in the 40–60 cm soil layer under the different tillage practices. There were no significant differences in porosity or soil bulk density under irrigation in the two years, and no significant difference was observed between TL and CK.

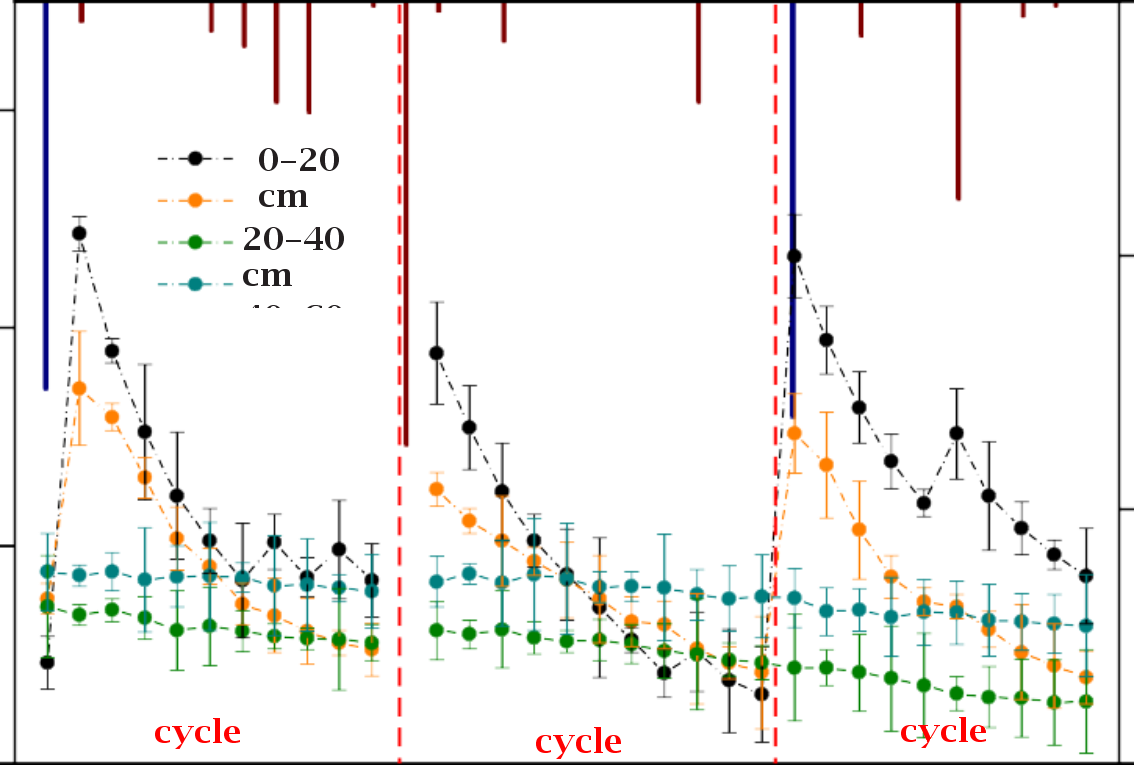

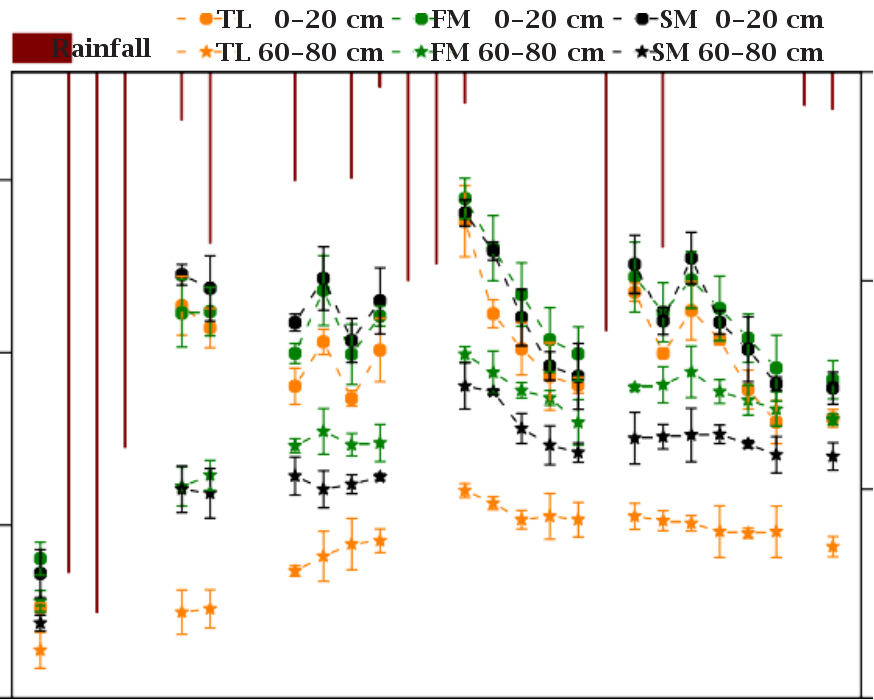

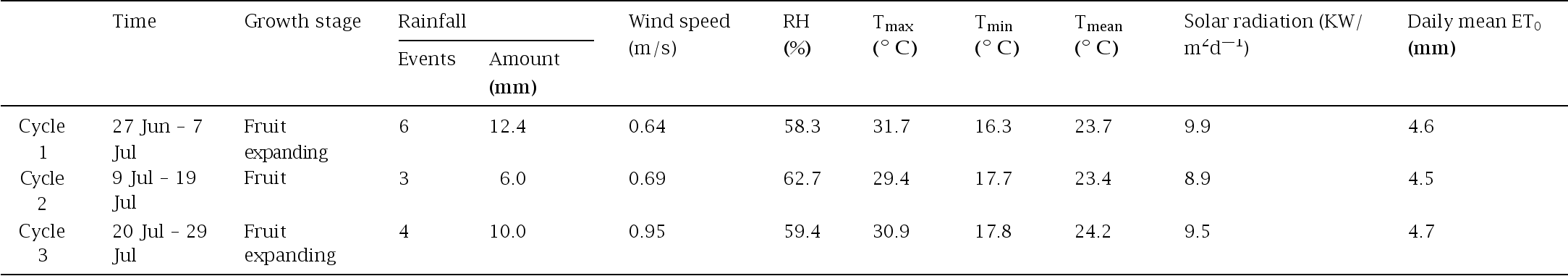

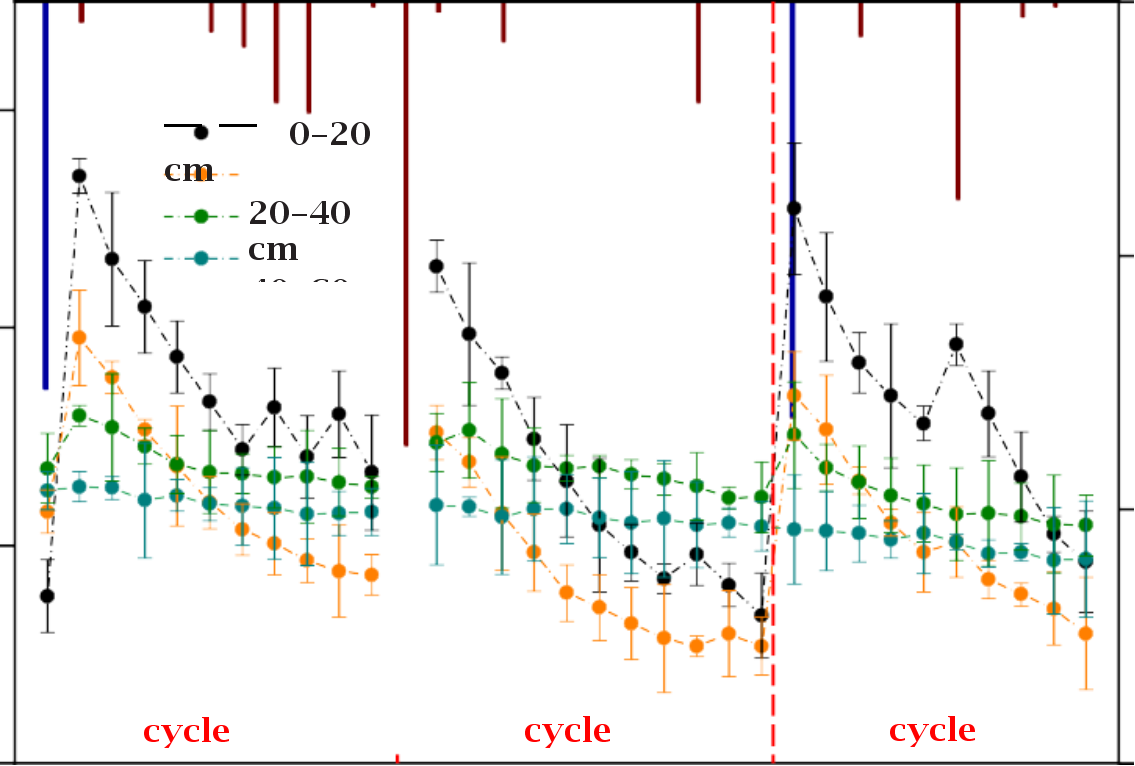

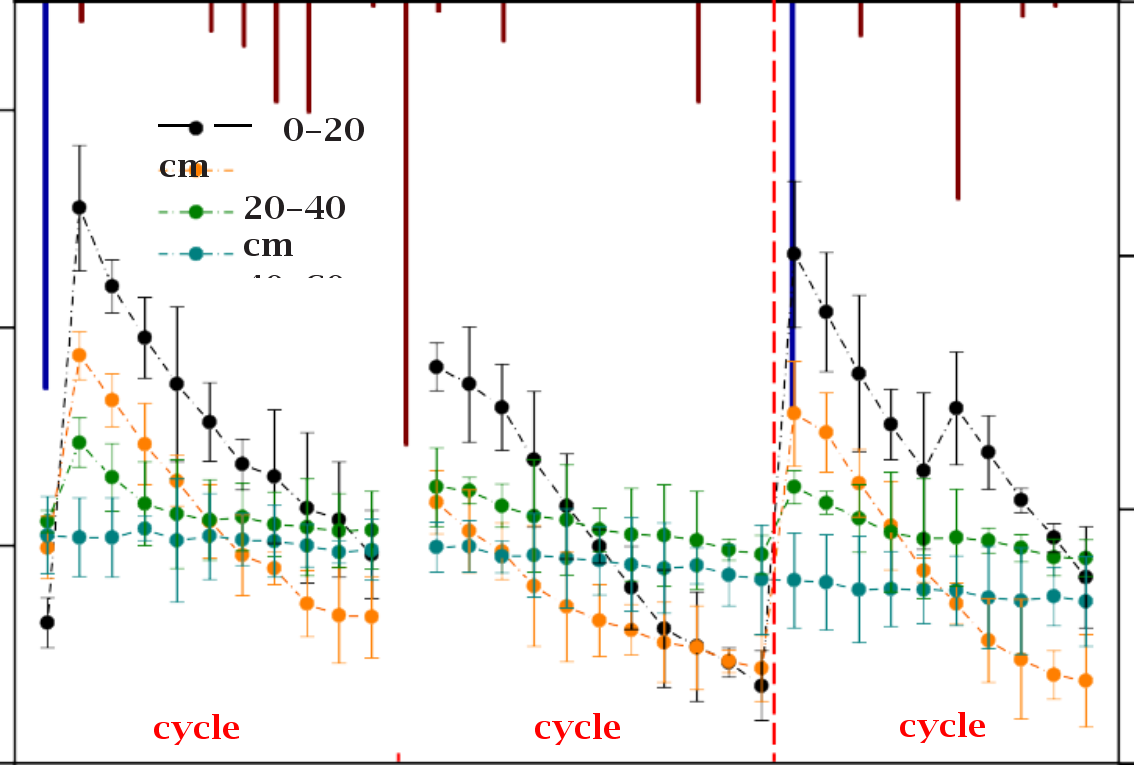

3.2. Variations in soil water after irrigation and rain

The meteorological factors in the three wet-dry cycles were generally the same (Table 1). Fig. 3 shows the variations in SWC of the three tillage practices at different soil depths after rain or irrigation. After irrigation, the SWC of the 0–40 cm soil layer increased rapidly and then gradually returned to a lower level. The increase in SWC in the 0–20 cm soil layer was greater than that in the 20–40 cm soil layer, which was related to water replenishment in the upper soil that occurred first after rainfall or irrigation. In the SM and FM treatments, the SWC of the 40–60 cm soil layer also increased, but there was no similar increase in the TL treat- ment. The SWC of the 60–80 cm soil layer did not change after irrigation and showed a gradually decreasing trend in July. When irrigation

Meteorological conditions of three wet-dry cycles in fruit expansion stage in 2020.

occurred, we found that the increase in soil water storage (SWS) was higher than the irrigation amount (Table 2), which could be due to accumulation of water around the emitters after irrigation. In the FM and SM treatments, the increased SWS was higher than that in the TL treatment Table 3.

The increase in SWS was always lower than rainfall due to canopy interception, surface runoff and soil evaporation. After the rain on 8 July, the TL treatment (15.04 mm) exhibited the greatest increase in SWS, while the lowest increase occurred in the SM treatment (12.80 mm). In addition, some small rainfall amounts occurred during the three cycles. When the rainfall was greater than 4 mm, the SWC of the 0–20 cm soil layers in TL and FM increased slightly, while SM only increased when larger rainfall occurred (7.8 mm on 25 July) during the three cycles Fig. 4 and Fig. 5.

The high frequency-high magnitude rainfall that occurred in August had a great impact on SWC, especially the continuous rainfall from August 4 to August 6 (Fig. 6 and Table 4). A total of 135.8 mm of rain fell from August 4 to August 6, which led to a sharp increase in SWC, and the increased SWS of SM (91.1 mm) was higher than those of TL (61.3 mm) and FM (78.6 mm). After another large continuous rainfall event

(rainfall of 41.4 mm from 16 Aug to 18 Aug), the same trend was pre- sent, and the increased SWS exhibited a trend of SM (34.9 mm) > FM (31.9 mm) > TL (26.7 mm). However, when the rainfall amounts were

small, SM always exhibited the smallest SWS increment (Table 4). After rainfall in August, the SWC of the 0–20 cm soil layer under the three tillage practices significantly improved, and no significant differences appeared among them (Fig. 6). However, in the deeper soil layer (80 cm), significantly more water recharge occurred in the two mulch- ing treatments.

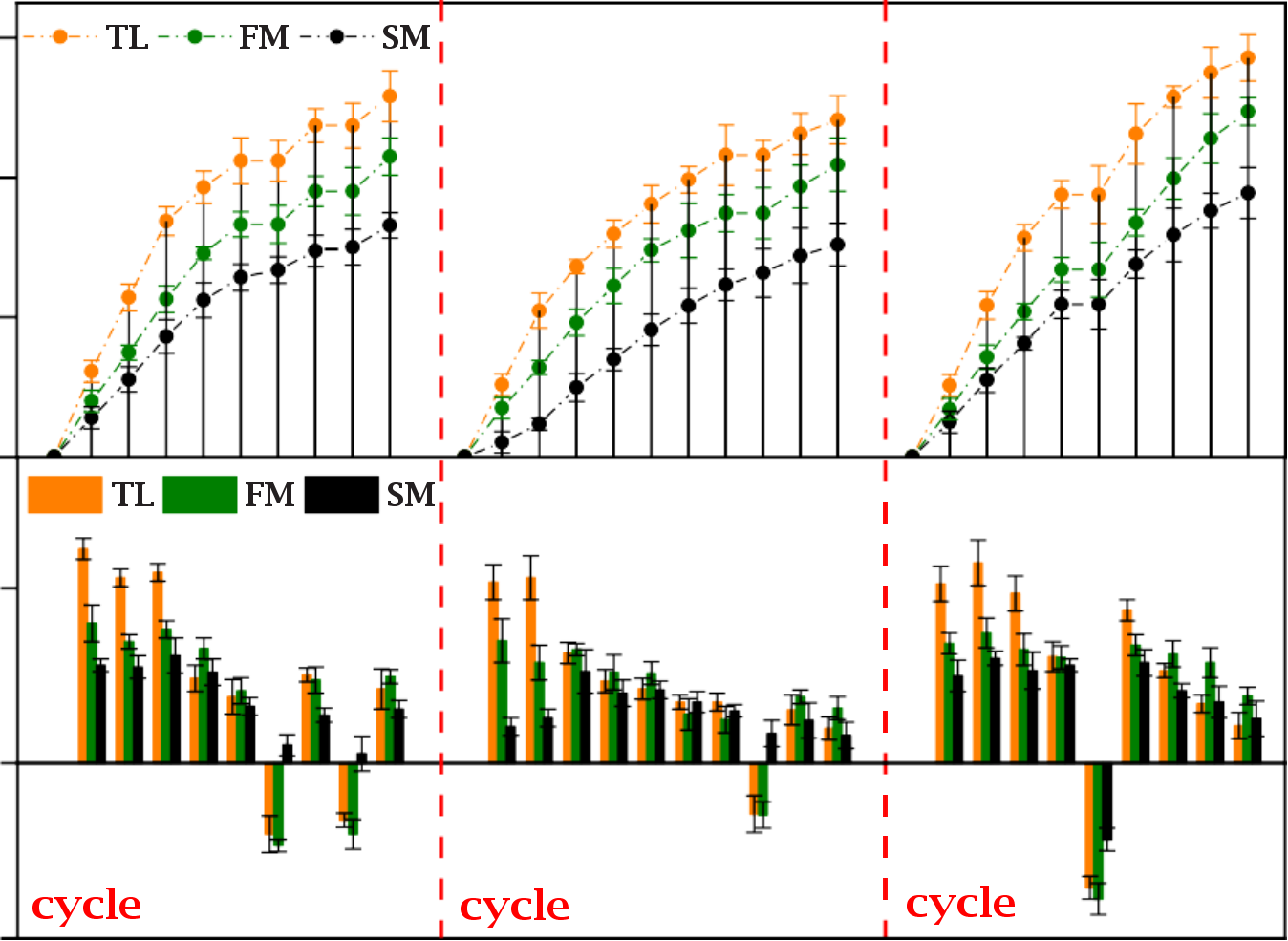

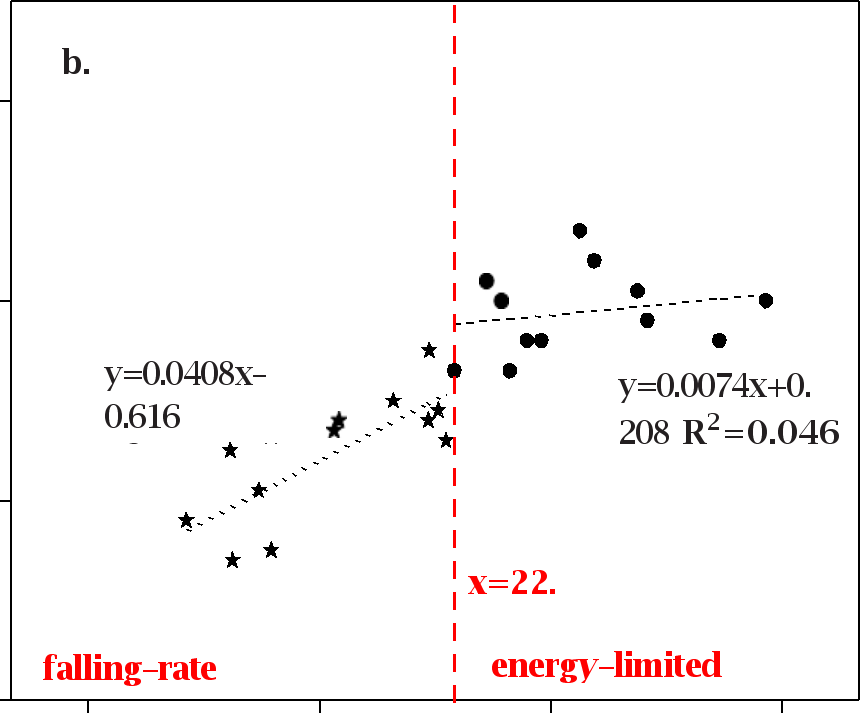

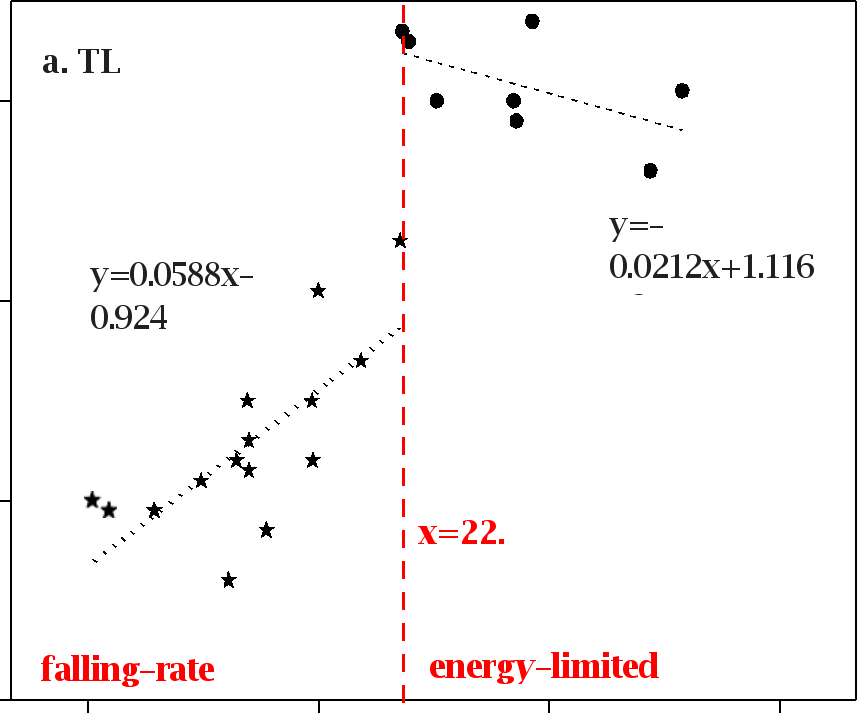

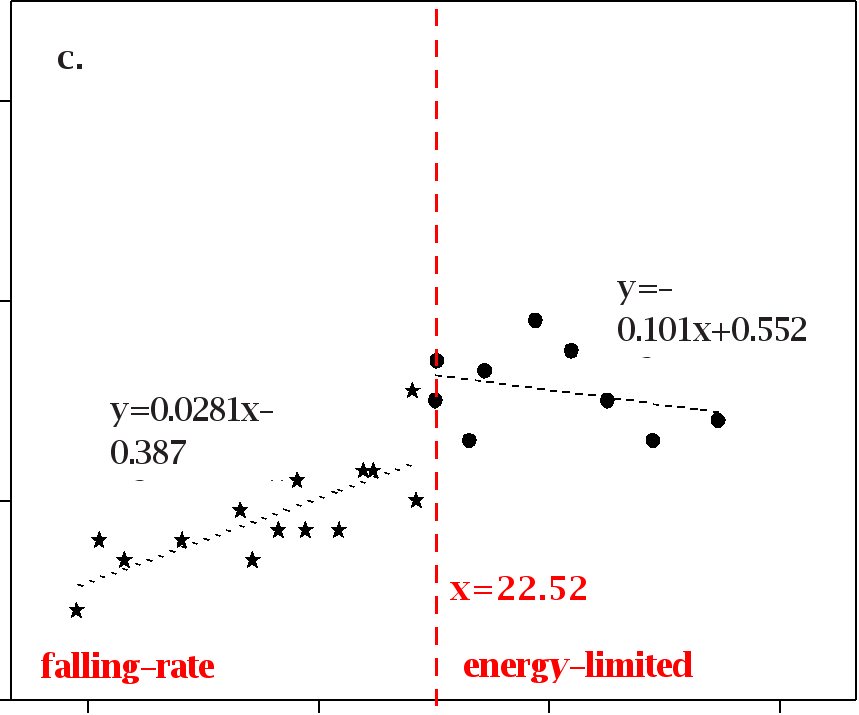

3.3. Variations of evaporation after irrigation or rain

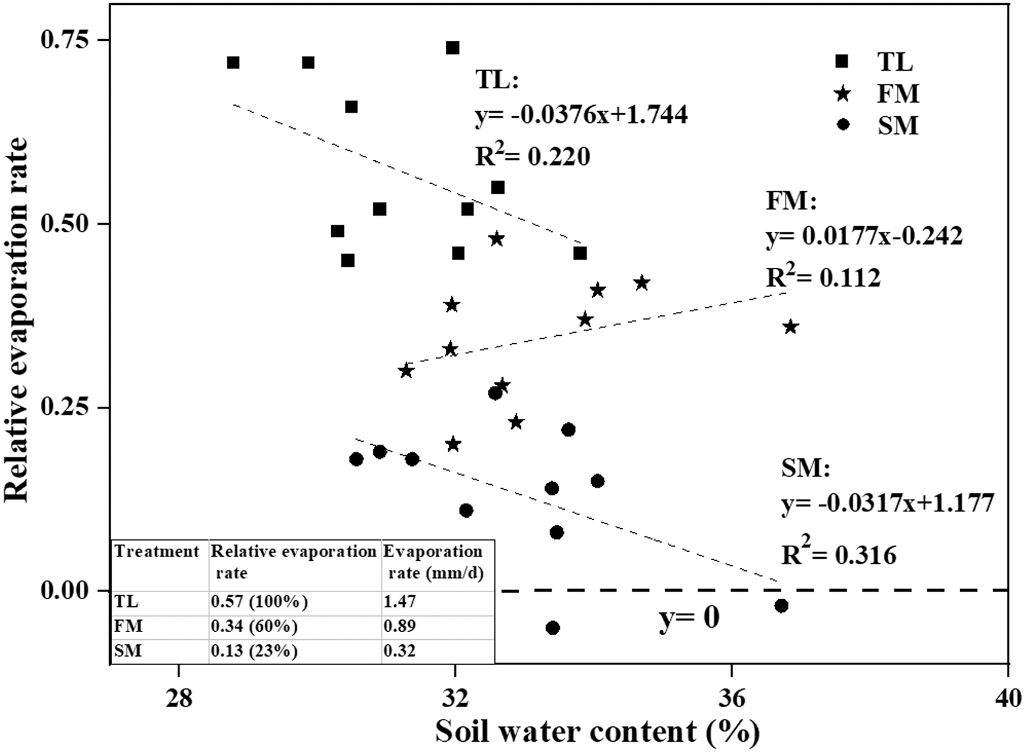

We analysed the relationship between soil evaporation and SWC in the 0–20 cm soil layer. The relative evaporation rate was introduced to eliminate the influence of meteorological factors and canopy shading on soil evaporation. Fig. 5 shows the relationship between the relative soil evaporation rate and SWC in the three wet-dry cycles. Thresholds of SWC between two evaporation stages were found in the process of soil evaporation. The thresholds for TL, FM and SM were 22.09%, 22.75% and 22.52%, respectively. When the SWC was above the threshold, the relative soil evaporation changed little with SWC, and there was no significant correlation between them. At this time, soil evaporation is in the energy-limited stage. However, when the SWC was below the threshold, the relative soil evaporation rate decreased linearly with the decrease in SWC, and extremely significant correlations were found in both the bare soil and mulching treatments. At this time, soil evapora- tion is in the falling-rate stage. Due to rainfall recharge, the SWC was above the threshold on the date we monitored in August, and no sig- nificant correlation was found between the relative evaporation rate and SWC (Fig. 7). This was consistent with the results in the energy-limited stage in the three wet-dry cycles.

Despite some differences, the same soil evaporation pattern occurred in the three wet-dry cycles. In the early stage of the wet-dry cycle, under

![]()

expanding

expanding

28

![]()

![]() 10

10

24

20

20

16

6/27 7/2 7/7

6/27 7/2 7/7

28

7/12 7/17

a. TL Date (month/day)

30

7/22 7/27

0

![]()

![]() 10

10

24

20

20

16 30

6/27 7/2 7/7 7/12 7/17 7/22 7/27

b. FM Date (month/day)

0

0

28

![]()

![]() 10

10

24

20

20

16 30

6/27 7/2 7/7 7/12 7/17 7/22 7/27

c. SM Date (month/day)

Fig. 3. Variation of volumetric soil water content in the three wet-dry cycles in fruit expansion stage in 2020. The error bars represent the standard deviations. TL: clear tillage with drip irrigation; FM: horticultural fabric mulching with drip irrigation; SM: corn straw mulching with drip irrigation.

![]()

![]()

Increase and consumption of soil moisture in the three wet-dry cycles in fruit expansion stage in 2020.

![]()

Cycle 2

Cycle 3

FM Irrigation 15.3 mm 23.90 ± 1.06ab 23.16 ± 0.64b 8.60 ± 0.53b 2.66 ± 0.30a

![]() SM Irrigation 15.3 mm 25.15 ± 0.51a 26.03 ± 041a 6.63 ± 0.36c 2.70 ± 0.20a

SM Irrigation 15.3 mm 25.15 ± 0.51a 26.03 ± 041a 6.63 ± 0.36c 2.70 ± 0.20a

TL Rainfall 17.5 mm 15.04 ± 0.41a 20.98 ± 0.77b 9.65 ± 0.69a 2.66 ± 0.19a

FM Rainfall 17.5 mm 14.70 ± 0.57a 23.48 ± 0.34a 8.37 ± 0.76a 2.70 ± 0.22a

SM Rainfall 17.5 mm 12.80 ± 0.35b 21.50 ± 0.18b 6.08 ± 0.61b 2.74 ± 0.17a

TL Irrigation 17.2 mm 24.64 ± 0.25b 22.98 ± 0.49b 11.43 ± 0.66a 2.60 ± 0.31a

FM Irrigation 17.2 mm 26.32 ± 0.83a 26.12 ± 1.13a 9.89 ± 0.40a 2.70 ± 0.28a

SM Irrigation 17.2 mm 27.68 ± 0.57a 25.06 ± 0.67a 7.56 ± 0.73b 2.77 ± 0.20a

![]()

Note: TL: clear tillage with drip irrigation; FM: horticultural fabric mulching with drip irrigation; SM: corn straw mulching with drip irrigation. Data are mean

± standard deviation of the three replicates. *Different letters within a column indicate significant differences among treatments at P = 0.05 level.

Evaporation rate in different evaporation stages in the three wet-dry cycles in fruit expansion stage in 2020, and the percentage in parentheses indicates the soil evaporation rate of each treatment relative to that of the TL treatment.

![]()

Treatment Energy-limited stage Falling-rate stage

![]() Relative evaporation rate Evaporation rate (mm/d) Soil water content (%) Relative evaporation rate Evaporation rate (mm/d) Soil water content (%)

Relative evaporation rate Evaporation rate (mm/d) Soil water content (%) Relative evaporation rate Evaporation rate (mm/d) Soil water content (%)

Note: TL: clear tillage with drip irrigation; FM: horticultural fabric mulching with drip irrigation; SM: corn straw mulching with drip irrigation.

![]() 8

8

4

0

![]() 2

2

0

-2

6/27

7/2

7/7

7/12

7/17

7/22

7/27

Date (month/day)

Fig. 4. Daily evaporation and cumulative soil evaporation in the three wet-dry cycles in fruit expansion stage in 2020. The error bars represent the standard de- viations. TL: clear tillage with drip irrigation; FM: horticultural fabric mulching with drip irrigation; SM: corn straw mulching with drip irrigation.

the same treatment, the soil evaporation rate was basically the same, and the cumulative soil evaporation increased steadily (energy-limited stage) (Fig. 4). In the later stage of the wet-dry cycle, evaporation gradually decreased as the soil inside the ML dried out, and the cumu- lative soil evaporation levelled off (falling-rate stage). Several rainfall events (more than 4 mm) in the three wet-dry cycles affected soil evaporation and even led to negative values (which were manually adjusted to 0 in the calculations of cumulative evaporation). These values were due to raindrops falling into the MLs, which resulted in increased ML weights.

In the energy-limited stage, mulching significantly reduced soil

evaporation. In the three wet-dry cycles, compared with bare soil, the mean evaporation rates decreased by approximately 35% and 48% in the FM and SM treatments, respectively (Table 3). In the rainy August, compared with TL, the mean evaporation rates decreased by approxi- mately 40% and 77% in the FM and SM treatments, respectively (inserted table in Fig. 7). In the falling-rate stage, SM reduced evapo- ration rates by 34% relative to TL, while no significant differences were found between TL and FM. SM significantly reduced cumulative evap- oration in all three wet-dry cycles. However, FM significantly reduced cumulative evaporation only in the first cycle, even if there were dif- ferences in the latter two cycles. The mean cumulative evaporation

0.0

18 21

24 27

0.0

18 21

24 27

Volumetric soil water content (%) Volumetric soil water content (%)

0.6

0.6

![]() 0.4

0.4

0.2

0.0

18 21

24 27

Volumetric soil water content (%)

Fig. 5. Relationships and linear regression equations between relative soil evaporation rate and gravimetric soil water content measured in each tillage practice in the three wet-dry cycles in fruit expansion stage in 2020. TL: clear tillage with drip irrigation; FM: horticultural fabric mulching with drip irrigation; SM: corn straw mulching with drip irrigation.

![]()

![]()

amounts for FM and SM in the three wet-dry cycles were 9.0 mm and

6.8 mm, respectively, which were 14% and 35% lower, respectively, than that of TL (10.5 mm).

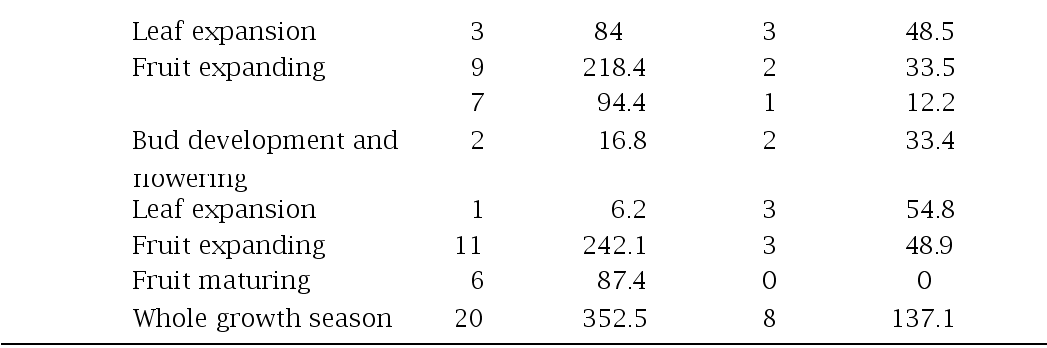

3.4. Yield and IWUE

In 2018, 2019 and 2020, 116.4 mm, 120.3 mm and 137.1 mm irri- gation were applied, respectively (Table 5). Due to the impact of COVID- 19, irrigation was carried out from late April in 2020, instead of starting in early April (the beginning of the growth season) like the other two years. Yields varied significantly among different years (Table 6). The lowest yield was present in 2018 due to the occurrence of a severe frost, which caused many flowers to be damaged. Yields under the irrigation treatments were significantly higher than those under rain feeding (CK), and mulching effectively increased yields compared with TL. The three-

year average yields indicated that yields improved by 24.1% and 20.6%, respectively, in FM (34.7 t ha—1) and SM (33.7 t ha—1) compared with TL (27.9 t ha—1). Simultaneously, mulching significantly increased IWUEs.

Compared with TL, the three-year average IWUE improved by 111.3% and 96.3% in FM and SM, respectively.

Soil bulk density and soil porosity are two key factors for good soil structure. These two factors directly affect the aeration and permeability of soil, water retention and migration, and the difficulty of root pene- tration. Capillary pores store capillary water, which is easily absorbed by crop roots and is used for crop transpiration and growth. Soil- detained water is stored within non-capillary pores and has the poten- tial to supplement capillary water when needed (Liu et al., 2013). Our study found that mulching effectively reduced soil bulk densities and increased soil porosities (both capillary and non-capillary) in the 0–40 cm soil layer. These results demonstrated that the soil structure of orchards can be substantially improved by mulching. Similar results

were observed in Kahlon et al. (2013) and Z˙ elazny & Licznar-Małan´czuk.

(2018). Moreover, soil bulk density presented a trend of first increasing and then decreasing with increasing soil depth, while soil porosity showed the opposite trend. The highest soil bulk density and lowest soil porosity occurred in the 20–40 cm soil layer. This may have been caused by the plough pan that was formed due to long-term tillage, which was consistent with the results of Gao et al. (2010).

![]()

![]()

![]()

0 Effective rainfall, irrigation during the different growth stages of apple trees.

![]() Bud development and flowering stage: early April to mid-May; Leaf expansion stage: late May to mid-June; Fruit expansion stage: late June to late August; Fruit

Bud development and flowering stage: early April to mid-May; Leaf expansion stage: late May to mid-June; Fruit expansion stage: late June to late August; Fruit

![]()

40 maturing stage: early September to fruit harvest.

Year Growth stage Effective rainfall Irrigation

![]()

![]()

![]() 20 Events Amount

20 Events Amount

(mm)

![]() 32

32

![]()

Events Amount (mm)

2018 Bud development and flowering

5 49.2 4 57.4

Leaf expansion 4 56.6 1 14.7

40 Fruit expanding 15 291.2 3 44.3

24 Fruit maturing 6 89.8 0 0

Whole growth season 30 486.8 8 116.4

Whole growth season 30 486.8 8 116.4

16

8/5

60

8/10 8/15 8/20 8/25 8/30

2019 Bud development and flowering

3 55.4 2 26.1

Date (month/d)

Fig. 6. Variation of volumetric soil water content of 0–20 cm and 60–80 cm soil layers in August 2020. The error bars represent the standard deviations. TL: clear tillage with drip irrigation; FM: horticultural fabric mulching with drip irrigation; SM: corn straw mulching with drip irrigation.

2020

Fruit maturing

Increased soil water storage after rain in August 2020.

Period Rainfall (mm) Monitoring date Increased soil water storage

(mm)

TL FM SM 4 Aug-6 Aug 135.8 8 Aug 61.3 78.6 91.1

9-Aug 16.4 12 Aug -0.4 -0.4 -2.6

12-Aug 10.4 13 Aug 6.3 7.2 6.7

14-Aug 10.2 15 Aug 10.4 7.0 8.0

16 Aug-18 Aug 41.4 18 Aug 26.7 31.9 34.9

23-Aug 24.8 24 Aug 20.1 20.8 20.2

25-Aug 16.8 26 Aug 12.8 12.6 11.6

![]()

Note: TL: clear tillage with drip irrigation; FM: horticultural fabric mulching with drip irrigation; SM: corn straw mulching with drip irrigation.

Fig. 7. Relationships and linear regression equations between relative evapo- ration rate and volumetric soil water content measured in each tillage practice in August 2020. TL: clear tillage with drip irrigation; FM: horticultural fabric mulching with drip irrigation; SM: corn straw mulching with drip irrigation. The inserted table shows the average relative evaporation rate and evaporation rate in August.

Note: When the rainfall ≥ 5 mm, the rainfall is effective rainfall. Due to the impact of COVID-19, irrigation was not carried out in the early and middle April in 2020.

Under the effects of tillage and raindrops, aggregates with porous and permeable properties are easily broken. Le Bissonnais et al. (2005) reported that under intense rainfall, both slaking and raindrop impacts will break down dry soil aggregates. Broken soil aggregates are easily eroded by wind and water on the soil surface and settle under the effect of gravity. When rainfall occurs, surface seals are often formed on the soil surface (Rahma et al., 2017), which increase soil bulk density and reduce the hydraulic properties of soil. This can be ascribed to compaction due to raindrop impact and “washed in” smaller soil parti- cles plug partial pores in the surface. Formation of a surface seal significantly decreases the infiltrability of soil. When the rainfall in- tensity is greater than the infiltration rate, surface ponds and runoff will be produced. Horticultural fabric and straw form a protective layer on the soil surface, which can reduce the impact of raindrops and protect the soil from water and wind erosion. In addition, straw gradually de- composes into organic matter, which aids the formation of soil aggre- gates. These factors were conducive to the formation of a good soil structure and avoid formation of surface seal.

In this study, when irrigation took place, both FM and SM effectively increased soil infiltration relative to TL, which can be attributed to two factors. The first is that good soil structure increased the vertical infil- tration of irrigation water. Another explanation is that mulching covered the wetted soil surface and reduced evaporation. However, some dif- ferences existed in infiltration after rain between FM and SM. Both FM and SM greatly increased soil infiltration relative to TL when heavy rain occurred, and SM had a better effect. When light rain occurred, no sig- nificant differences were found between TL and FM, while SM always reduced infiltration in comparison to TL.

Horticultural fabric is a woven permeable polyethylene material. Straw itself forms a rainfall collection and absorption layer and addi- tional barriers on the soil surface (Liao et al., 2021). Therefore, when light rain occurs, 10 cm thick straw mulch absorbs part of the rainfall and loses it through evaporation. Even so, when heavy rain occurs, straw can promote soil infiltration by increasing the roughness and tortuosity of flow paths and thus reduce flow velocities (Rahma et al., 2017). Prosdocimi et al. (2016) reported that the formation of surface ponds and runoff was effectively delayed and prevented by straw mulch. Similar results were observed in Liu et al. (2012), who reported that runoff and nutrient losses were effectively controlled by straw mulch.

![]()

![]()

![]() Yield and irrigation water use efficiency (IWUE) in the three consecutive years.

Yield and irrigation water use efficiency (IWUE) in the three consecutive years.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Treatment 2018 2019 2020

Irrigation (mm) Yield (t ha—1) IWUE Irrigation (mm) Yield (t ha—1) IWUE Irrigation (mm) Yield (t ha—1) IWUE

![]()

TL 116.4 17.8 ± 1.4ab* 3.1 ± 1.2a 120.3 36.4 ± 1.2ab 6.7 ± 1.1b 137.1 29.7 ± 3.6b 4.6 ± 2.6b

FM 116.4 21.3 ± 3.5a 6.1 ± 3.0a 120.3 44.4 ± 7.6a 13.4 ± 4.8a 137.1 38.3 ± 4.9a 10.8 ± 3.6a

SM 116.4 21.9 ± 4.5a 6.6 ± 3.9a 120.3 43.5 ± 4.0a 12.7 ± 2.1ab 137.1 35.7 ± 1.8a 8.9 ± 1.3a

![]()

CK 0 14.2 ± 0.4b 0 28.3 ± 2.0b 0 23.4 ± 3.1c

Note: TL: clear tillage with drip irrigation; FM: horticultural fabric mulching with drip irrigation; SM: corn straw mulching with drip irrigation; CK: clear tillage with rain feeding. Data are mean ± standard deviation of the three replicates. *Different letters within a column indicate significant differences among treatments at P = 0.05 level.

![]()

![]()

![]()

When the rainfall intensity is greater than the infiltration rate, the ab- sorption capability of straw provides additional pathways for water infiltration (Li et al., 2011). This water trapped in straw will gradually be released over several days and result in increased infiltration (Liu et al., 2014). In our study, very low or even negative soil evaporation under SM in August can also prove this point because this trapped water was released into the MLs, which resulted in increased water in the MLs (Fig. 7).

Rainfall is the most important soil water supply source for orchards on the Loess Plateau. When it rains, rainfall first infiltrates the surface soil, and large gradients in the gravitational potential and matrix po- tential in the vertical direction are formed. Water will continue to penetrate downwards until the wetting front stops moving, and the water compensation depth reaches a maximum value. In our research, irrigation increased SWC in the 40–60 cm soil layer under FM and SM; however, no similar increase was found in TL. Based on this result, we can infer that mulching can effectively promote water compensation in deeper soil layers. This is also reflected during the high frequency-high magnitude rainfall in August, where significantly more water recharge occurred in deeper soil (60–80 cm) in the two mulching treatments. Song et al. (2020) also observed similar results. This could be because i) thick plough pans and low porosity under the TL treatment are not conducive to water infiltration; ii) the SM and FM treatments have higher SWCs than TL in the upper soil, so a larger water potential gradient between the upper soil and deeper soil will form after rainfall and irrigation, which can promote downward transmission of water; and

iii) more water evaporates in the TL treatment.

Soil evaporation is affected by meteorological factors, canopy shading and SWC. We measured the leaf area index in the three wet-dry cycles, and there were no significant differences among the three treatments (Table 2). When soil is wet, the soil water at the soil- atmosphere interface evaporates due to heat from solar radiation, which leads to a decrease in soil water potential at the soil-atmosphere interface. Under the action of capillary forces, soil water moves from the underlying soil with higher water potential to the soil-atmosphere interface (Liu et al., 2008). Mulching on the soil surface forms an insu- lating layer, which can effectively slow down and hinder the exchange of water and energy by preventing solar radiation heat from directly reaching the soil surface.

In our study, both FM and SM significantly reduced soil evaporation rates in the energy-limited stage, and SM had a better effect. In the falling-rate stage, SM still reduced soil evaporation compared with TL, even if the reduction was lower than that in the energy-limited stage, while FM did not. It was speculated that this may be due to the higher SWC of FM in the falling-rate stage. This finding contrasts with that of Zribi et al. (2015), who found that mulching did not significantly reduce soil evaporation in the falling-rate stage. This could be because their research monitored the wet-dry cycle for a longer period (30 days), so the soil evaporation rate was very low in the falling-rate stage for all treatments. At the same time, the accuracy of evaporation measure- ments over a longer time without renewing undisturbed soil in the field experiments should also be considered. We noticed that in the energy-limited stage, the soil evaporation rate under SM in August

(0.32 mm/d) was significantly lower than that in the three wet-dry cy- cles (1.11 mm/d) (inserted table in Fig. 7 and Table 3). This may be because high frequency-high magnitude rainfall caused the straw to be soaked with water, which greatly hindered the exchange of water and vapor between the soil and atmosphere. Simultaneously, when water that soaks the straw evaporates, it absorbs large amounts of heat and reduces surface soil temperatures. In addition, we analysed the rela- tionship between the relative evaporation rate and surface SWC and found the existence of a threshold of SWC (22.09% 22.75%) between the energy-limited stage and falling-rate stage. In a similar study, Sun et al. (2012) reported that evaporation dropped to very low levels when the SWC of the soil surface decreased. Zribi et al. (2015) found that soil evaporation and SWC were positively and linearly correlated because most observations pertain to the falling-rate stage of soil evaporation.

![]() Yields are affected by many factors, and soil water is a key limiting factor on the Loess Plateau. Combining mulching with irrigation can increase water inputs to compensate for water deficits caused by insuf- ficient rainfall, and on the other hand, it can effectively maintain soil moisture by reducing evaporation and promoting infiltration. In this study, irrigation effectively increased yields for three consecutive years, and mulching accentuated this trend. Moreover, compared with TL, mulching greatly improved IWUE. This finding was also reported by Zhang et al. (2014). Due to the contradiction between water supply and consumption, deficit irrigation has been widely studied for optimizing water application. Some scholars have studied applying a combination of mulching and deficit irrigation in semiarid areas and have reported improvements in yields and water use efficiency (Yang et al., 2018; Rashid et al., 2019). Sokalska et al. (2009) reported that in the apple orchards with drip irrigation system, more than 92.3% of the fine roots of mature apple trees are distributed in the 0–80 cm soil layer, and more than 76.7% of the fine roots are distributed in the 0–60 cm soil layer. However, in our study, after irrigation, only 0–40 cm soil layer greatly increased SWS, while SWS of 40–80 cm soil layer increased little. In order to make irrigation water infiltration deeper and directly transport to the roots, surge-root irrigation was invented (Wu et al.,2010), and some scholars reported its applicability in semi-arid orchards (Dai et al., 2019; Zhong et al., 2019).

Yields are affected by many factors, and soil water is a key limiting factor on the Loess Plateau. Combining mulching with irrigation can increase water inputs to compensate for water deficits caused by insuf- ficient rainfall, and on the other hand, it can effectively maintain soil moisture by reducing evaporation and promoting infiltration. In this study, irrigation effectively increased yields for three consecutive years, and mulching accentuated this trend. Moreover, compared with TL, mulching greatly improved IWUE. This finding was also reported by Zhang et al. (2014). Due to the contradiction between water supply and consumption, deficit irrigation has been widely studied for optimizing water application. Some scholars have studied applying a combination of mulching and deficit irrigation in semiarid areas and have reported improvements in yields and water use efficiency (Yang et al., 2018; Rashid et al., 2019). Sokalska et al. (2009) reported that in the apple orchards with drip irrigation system, more than 92.3% of the fine roots of mature apple trees are distributed in the 0–80 cm soil layer, and more than 76.7% of the fine roots are distributed in the 0–60 cm soil layer. However, in our study, after irrigation, only 0–40 cm soil layer greatly increased SWS, while SWS of 40–80 cm soil layer increased little. In order to make irrigation water infiltration deeper and directly transport to the roots, surge-root irrigation was invented (Wu et al.,2010), and some scholars reported its applicability in semi-arid orchards (Dai et al., 2019; Zhong et al., 2019).

The rainfall in July 2020 (45.1 mm) was much lower than the average rainfall (98.0 mm) in July (from 1971 to 2020), while the rainfall in August (271.2 mm) was much higher than the average rainfall in August (101.4 mm). However, this rare rainfall distribution provides a good opportunity for our experiment to observe water infiltration and evaporation under different rainfall conditions. On the other hand, the two irrigation events we chose are representative because the irrigation amounts in each irrigation event were nearly the same (11.9–17.4 mm in the three years).

In this study, corn straw and horticultural fabric were selected as mulching materials. Corn is widely planted in local areas, so it is inex- pensive and can be widely used. However, straw mulching is more dispersed, and it can easily drift when it is windy or rainy, so we added a nylon net to stabilize it. It should be noted that in August, soil evapo- ration was very low, even negative, this may mean that the soaked straw mulch reduce soil air permeability and is not conducive to crop root

![]()

![]()

![]()

respiration. Rahma et al. (2017) reported that in extreme rainfall events, the use of straw mulching with high mulching rates on sloping land may more easily induce soil loss. Therefore, we do not recommend the use of straw mulch with high mulching rates in farmland in rain-rich areas, especially on sloping land, but it can be used to restore soil water storage for flat land. Compared with plastic film, horticultural fabric has a longer service life with the same low price. In our research, in the three-year test, only the edges of the horticultural fabric were slightly damaged, so it can also effectively minimise plastic pollution. Moreover, application of straw mulching and horticultural fabric mulching does not have a high demand for labour. Taken together, both FM and SM have potential for application in orchards in semiarid areas to improve soil and moisture conditions in the root zone. In addition, we agree with Zribi et al. (2015) that mulching would be more beneficial in high-frequency irrigation systems with wet soil surfaces most of the time than in low-frequency irrigation systems because mulching has a better evaporation control effect on wet soil surfaces.

On the Loess Plateau, in the water cycle of fields, infiltration after irrigation or rainfall is the most important method of water input, and evaporation and transpiration are the main methods of water con- sumption. Through field experiments, we studied infiltration and evaporation after irrigation and rainfall. However, further research on transpiration is needed to understand the complete water cycle of fields. In addition, mulching greatly changes the soil environment in root zones, and roots are the main tissue for plants to absorb water and nu- trients. Therefore, to explain crop responses, more research is required on roots.

The results of this study show that mulching with no tillage effec- tively improved soil physical properties by reducing soil bulk density and increasing porosity. In the 0–40 cm soil layer, the mean soil bulk densities of FM and SM were 2.8% and 4.5% lower than TL, and the mean porosity were 4.7% and 9.0% higher than TL. By changing the structure of the underlying surface of the field, mulching increased infiltration after irrigation and heavy rain. Due to water absorption by the straw layer, straw mulching reduced infiltration when light rain occurred.

Regardless of whether the soil is in the energy-limited stage or falling-rate stage, mulching can effectively reduce soil evaporation, and straw mulching has a better effect. In the energy-limited stage, evapo- ration and soil moisture content showed a very significant linear rela- tionship, but in the falling-rate stage, there was no significant correlation between them. In August, because the straw was soaked with water, soil evaporation was extremely low and even negative, which may affect soil permeability. Therefore, we do not recommend the use of straw mulch with a high mulching rate in farmlands in rain-rich areas. Mulching has a better evaporation control effect on wet soil surfaces, therefore, mulching would be more beneficial in high-frequency irri- gation systems from the perspective of inhibiting evaporation.

In three consecutive years, mulching effectively increased apple yields and IWUE. The three-year average yields indicated that yields improved by 24.1% and 20.6%, respectively, in FM and SM compared with TL. However, to understand the complete water cycle of the fields, further research is needed on transpiration. In addition, more research is required on roots to explain the response of crops to mulching.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Devel- opment Project (grant number: 2016YFC0400204) and the Science and Technology Plan Project of the Water Conservancy Department of Shaanxi Province (grant number: 2020slkj-08).

Abd El-Wahed, M.H., Ali, E.A., 2013. Effect of irrigation systems, amounts of irrigation water and mulching on corn yield, water use efficiency and net profit. Agric. Water Manag. 120, 64–71.

Allen, R.G., Pereira, L.S., Raes, D.S., Smith, M., 1998. Crop Evapotranspiration Guidelines for Estimating Crop Water Requirements. In: FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper, vol. 56. FAO, Rome, p. 300.

Awe, G.O., Reichert, J.M., Wendroth, O.O., 2015. Temporal variability and covariance structures of soil temperature in a sugarcane field under different management practices in southern Brazil. Soil Tillage Res. 150, 93–106.

Bao, S., 2007. Soil and Agricultural Chemistry Analysis. China Agricultural Press, Beijing.

Cao, S.X., Chen, L., Yu, X.X., 2009. Impact of China’s grain for green project on the landscape of vulnerable arid and semi-arid agricultural regions: a case study in northern Shaanxi Province. J. Appl. Ecol. 46, 536–543.

Carney, K.M., Matson, P.A., 2005. Plant communities, soil microorganisms, and soil carbon cycling, does altering the world belowground matter to ecosystem functioning? Ecosystems 8 (8), 928–940.

Chakraborty, D., Nagarajan, S., Aggarwal, P., Gupta, V.K., Tomar, R.K., Garg, R.N., Sahoo, R.N., Sarkar, A., Chopra, U.K., Sarma, K.S.S., Kalra, N., 2008. Effect of mulching on soil and plant water status, and the growth and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) in a semi-arid environment. Agric. Water Manag. 95 (12), 1323–1334.

Chen, Y.L., Liu, T., Tian, X.H., Wang, X.F., Li, M., Wang, S.X., Wang, Z.H., 2015. Effects of plastic film combined with straw mulch on grain yield and water use efficiency of winter wheat in Loess Plateau. Field Crop Res. 172, 53–58.

Chen, Y.X., Wen, X.X., Sun, Y.L., Zhang, J.L., Wu, W., Liao, Y.C., 2014. Mulching practices altered soil bacterial community structure and improved orchard productivity and apple quality after five growing seasons. Sci. Hortic. 172, 248–257.

Dai, Z.G., Fei, L.J., Huang, D.L., Zeng, J., Chen, L., Cai, Y.H., 2019. Coupling effects of irrigation and nitrogen levels on yield, water and nitrogen use efficiency of surge- root irrigated jujube in a semiarid region. Agric. Water Manag. 213, 146–154.

Du, S.Q., Kang, S.Z., Li, F.S., Du, T.S., 2017. Water use efficiency is improved by alternate partial root-zone irrigation of apple in arid northwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 179, 184–192.

Gao, M.S., Liao, Y.C., LI, X., Huang, J.H., 2010. Effects of different mulching patterns on soil water-holding capacity of non-irrigated apple orchard in the Weibei Plateau. Sci. Hortic. 43 (10), 2080–2087.

Gao, X.D., Liu, Z.P., Zhao, X.N., Ling, Q., Huo, G.P., Wu, P.T., 2018. Extreme natural drought enhances interspecific facilitation in semiarid agroforestry systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 265, 444–453.

Jorda´n, A., Zavala, L.M., Gil, J., 2010. Effects of mulching on soil physical properties and runoff under semi-arid conditions in southern Spain. Catena 81 (1), 77–85.

Kahlon, M.S., Lal, R., Ann-Varughese, M., 2013. Twenty two years of tillage and mulching impacts on soil physical characteristics and carbon sequestration in Central Ohio. Soil Tillage Res. 126, 151–158.

Khan, M., Gong, Y.B., Hu, T.X., Lal, R., Zheng, J.K., Justine, M.F., Azhar, M., Che, M.X., Zhang, H.T., 2016. Effect of Slope, Rainfall Intensity and Mulch on Erosion and Infiltration under Simulated Rain on Purple Soil of South-Western Sichuan Province, China. In: China Water, 8, p. 528.

Le Bissonnais, Y., Cerdan, O., Lecomte, V., Benkhadra, H., Souch`ere, V., Martin, P., 2005.

Variability of soil surface characteristics influencing runoff and interrill erosion. Catena 62 (2–3), 111–124.

Li, H.C., Zhao, X.N., Gao, X.D., Ren, K.M., Wu, P.T., 2018. Effects of water collection and mulching combinations on water infiltration and consumption in a semiarid rainfed orchard. J. Hydrol. 558, 432–441.

Li, Q.Q., Chen, Y.H., Liu, M.Y., Zhou, X.B., Yu, S.L., Dong, B.D., 2008. Effects of irrigation and straw mulching on microclimate characteristics and water use efficiency of winter wheat in North China. Plant Prod. Sci. 11, 161–170.

Li, X.H., Zhang, Z.Y., Yang, J., Zhang, G.H., Wang, B., 2011. Effects of Bahia Grass cover and mulch on runoff and sediment yield of sloping red soil in Southern China.

Liao, Y., Cao, H.X., Xue, W.K., Liu, X., 2021. Effects of the combination of mulching and deficit irrigation on the soil water and heat, growth and productivity of apples.

Agric. Water Manag. 243, 106482.

Liu, C., Wang, Y., Zhan, K., Duan X.S, J.W., 2008. The study of influence of straw mulch amount to soil moisture evaporation in farmland. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 24 (5), 448–451.

Liu, Y., Tao, Y., Wan, K.Y., Zhang, G.S., Liu, D.B., Xiong, G.Y., Chen, F., 2012. Runoff and nutrient losses in citrus orchards on sloping land subjected to different surface mulching practices in the Danjiangkou Reservoir area of China. Agric. Water Manag. 110, 34–40.

Liu, Y., Gao, M.S., Wu, W., Tanveer, S.K., Wen, X.X., Liao, Y.C., 2013. The effects of conservation tillage practices on the soil water-holding capacity of a non-irrigated apple orchard in the Loess Plateau. China Soil Tillage Res. 130, 7–12.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Liu, Y., Wang, J., Liu, D.B., Li, Z.G., Zhang, G.S., Tao, Y., Xie, J., Pan, J.F., Chen, F., 2014.

Straw mulching reduces the harmful effects of extreme hydrological and temperature conditions in citrus orchards. Plos One 9 (1), 87094.

Long, Tao, Xiong, H.G., Li, B.F., Zhang, J.B., 2010. Field experiment of measurement accuracy influencing factors of micro-lysimeters. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 26 (5), 21–26.

Olasantan, F.O., 1999. Effect of time of mulching on soil temperature and moisture regime and emergence, growth and yield of white yam in western Nigeria. Soil Tillage Res. 50 (3), 215–221.

Prosdocimi, M., Jorda´n, A., Tarolli, P., Keesstra, S., Novara, A., Cerd`a, A., 2016. The

immediate effectiveness of barley straw mulch in reducing soil erodibility and surface runoff generation in Mediterranean vineyards. Sci. Total Environ. 547, 323–330.

Rahma, A.E., Wang, W., Tang, Z.J., Lei, T.W., Warrington, D.N., Zhao, J., 2017. Straw mulch can induce greater soil losses from loess slopes than no mulch under extreme rainfall conditions. Agric. Meteorol. 232, 141–151.

Ram, H., Dadhwal, V., Vashist, K.K., Kaur, H., 2013. Grain yield and water use efficiency of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) in relation to irrigation levels and rice straw mulching in North West India. Agric. Water Manag. 128, 92–101.

Rashid, M.A., Zhang, X.Y., Andersen, M.N., Olesen, J.E., 2019. Can mulching of maize straw complement deficit irrigation to improve water use efficiency and productivity of winter wheat in North China Plain? Agric. Water Manag. 213, 1–11.

Rodrigues, M.Aˆ., Correia, C.M., Claro, A.M., Ferreira, I.Q., Barbosa, J.C., Moutinho-

Pereira, J.M., Bacelar, E.A., Fernandes-Silva, A.A., Arrobas, M., 2013. Soil nitrogen availability in olive orchards after mulching legume cover crop residues. Sci. Hortic. 158, 45–51.

Sarkar, S., Paramanick, M., Goswami, S.B., 2007. Soil temperature, water use and yield of yellow sarson (Brassica napus L.var. glauca) in relation to tillage intensity and mulch management under rainfed lowland ecosystem in eastern India. Soil Tillage Res. 93 (1), 94–101.

Singh, B., Eberbach, P.L., Humphreys, E., Kukal, S.S., 2011. The effect of rice straw mulch on evapotranspiration, transpiration and soil evaporation of irrigated wheat in Punjab, India. Agric. Water Manag. 98 (12), 1847–1855.

Smets, T., Poesen, J., Knapen, A., 2008. Spatial scale effects on the effectiveness of organic mulches in reducing soil erosion by water. Earth Sci. Rev. 89 (1–2), 1–12.

Sokalska, D.I., Haman, D.Z., Szewczuk, A., Sobota, J., Deren´, D., 2009. Spatial root distribution of mature apple trees under drip irrigation system. Agric. Water Manag. 96 (6), 917–924.

Song, X.L., Wu, P.T., Gao, X.D., Yao, J., Zou, Y.F., Zhao, X.N., Siddique, K.H., M. Hu, W.,

2020. Rainwater collection and infiltration (RWCI) systems promote deep soil water

and organic carbon restoration in water-limited sloping orchards. Agric. Water Manag. 242, 106400.

Steinmetz, Z., Wollmann, C., Schaefer, M., Buchmann, C., David, J., Tro¨ger, J.,

Mun˜oz, K., Fro¨r, O., Schaumann, G.E., 2016. Plastic mulching in agriculture. Trading short-term agronomic benefits for long-term soil degradation? Sci. Total Environ. 550, 690–705.

Sun, H.Y., Shao, L.W., Liu, X.W., Miao, W.F., Chen, S.Y., Zhang, X.Y., 2012.

Determination of water consumption and the water-saving potential of three mulching methods in a jujube orchard. Eur. J. Agron. 43, 87–95.

Wang, H., Wang, C.B., Zhao, X.M., Wang, F.L., 2015. Mulching increases water-use efficiency of peach production on the rainfed semiarid Loess Plateau of China. Agric. Water Manag. 154, 20–28.

Wang, Y.J., Xie, Z.K., Malhi, S.S., Vera, C.L., Zhang, Y.B., Wang, J.N., 2009. Effects of rainfall harvesting and mulching technologies on water use efficiency and crop yield in the semi-arid Loess Plateau. China Agric. Water Manag. 96 (3), 374–382.

Wu, P.T., Zhu, D.L., Wang, Y.K., 2010. Research and application of surge-root irrigation.

J. Drain. Irrig. Mach. Eng. 28, 354–357.

Yang, J., Mao, X.M., Wang, K., Yang, W.C., 2018. The coupled impact of plastic film mulching and deficit irrigation on soil water/heat transfer and water use efficiency of spring wheat in Northwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 201, 232–245.

Yang, M., Wang, S.F., Zhao, X.N., Gao, X.D., Liu, S., 2020. Soil properties of apple orchards on China’s Loess Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 723, 138041.

Z˙ elazny, W.R., Licznar-Małan´czuk, M., 2018. Soil quality and tree status in a twelve-year-

old apple orchard under three mulch-based floor management systems. Soil Tillage Res. 180, 250–258.

Zhang, Q.T., Wang, S.P., Li, L., Inoue, M., Xiang, J., Qiu, G., Jin, W., 2014. Effects of mulching and sub-surface irrigation on vine growth, berry sugar content and water use of grapevines. Agric. Water Manag. 143, 1–8.

Zhang, S.L., Lovdahl, L., Grip, H., Tong, Y.N., Yang, X.Y., Wang, Q.J., 2009. Effects of mulching and catch cropping on soil temperature, soil moisture and wheat yield on the Loess Plateau of China. Soil Tillage Res. 102 (1), 78–86.

Zhao, C.L., Liu, Y., Wang, J.T., Dong, X.L., Li, Y.G., Sun, H.Y., 2020. Pan materials and the working environment affect water evaporation measurements. J. Drain. Irrig. Mach. Eng. 09 (08), 1672–3317.

Zhong, Y., Fei, L.J., Li, Y., Zeng, J., Dai, Z.G., 2019. Response of fruit yield, fruit quality, and water use efficiency to water deficits for apple trees under surge-root irrigation in the Loess Plateau of China. Agric. Water Manag. 222, 221–230.

Zribi, W., Aragü´es, R., Medina, E., Faci, J.M., 2015. Efficiency of inorganic and organic mulching materials for soil evaporation control. Soil Tillage Res. 148, 40–45.

![]()